Hi Everyone,

Considering the serious threat that Covid-19 poses to our physical health as well as our social, financial and economic health, I am putting together a series of posts that will investigate the impact this virus is having and will likely to have in the short, medium, and long run. I am not a medical doctor or a scientist. I am an economist. I will be using my economics background to analyse the expected impact this virus will have on our lives. This series of posts will cover the following.

- Identifying the threat

- The fragility of the world we live in

- Impact on prices and quantity of goods and services in absence of Government Intervention

- Actions taken or could be taken by Governments

- Possible Impact of Government intervention on the economy

- The social costs of Covid-19 and responses to it

- Winners and losers from the outbreak

- The road ahead (positive vs. negative scenarios) and what we could learn

In Part 5 of this series, I will be looking at how some of the Government interventions that I identified in Part 4 could affect the economy. I will be looking at output, unemployment, inflation, wealth distribution, debt and the impact on recovery. The analysis in this post is very broad and only intended to provide a general idea of how Government intervention could affect economies. It is likely that different interventions will vary in terms of success for different countries.

Government and the economy

The extent of the role of Government in a country’s economy varies between different countries. The role of Government can be placed on a spectrum from least involvement (Laissez-faire) to complete control (command). The roles of Government, in the context of the economy, typically include the following:

- Providing goods defined as public goods.

- Redistributing income.

- Prevent or limit exploitation of workers and/or consumers.

- Incentivising production and consumption of merit goods.

- Disincentivising production and consumption of demerit goods.

- Providing stability to the economy.

- Stimulating economic growth.

The Government performs the above roles through expenditure, taxation and regulation. The Government spends to provide public goods. These could include national defence, law enforcement, drainage and sewers, roads, and street lighting. Government redistributes wealth by taxing higher income earners and paying low or no income earners. Governments enact minimum wages to prevent businesses exploiting workers and enact price ceilings to prevent businesses charging excessively for particular goods and services. Government provides directly or provides subsidies to businesses deemed to provide merit goods. Merit goods are likely to include education, housing, power and energy, and water. Governments ban or tax businesses deemed to provide demerit goods. Demerit goods are likely to include tobacco, alcoholic beverages, recreational drugs, gambling, junk food and prostitution. Governments attempt to provide stability to the economy. To prevent a recession they increase expenditure and reduce taxes. To prevent inflation, they decrease expenditure and increase tax. Sometimes tax revenue is insufficient to cover Government expenditure; therefore, Governments borrow money. The borrowed money plus interest is required to be paid. These payments come out of future tax revenue. There is a possibility that Government expenditure could be increased by increased money supply. Instead of paying through tax, people would pay through higher prices for goods and services (i.e. inflation).

Macroeconomics used to explain the impact

To explain the impact of price and output, I will be using a simple aggregate demand and aggregate supply (AD-AS) model. The AD-AS model will broadly explain the impact on price (i.e. inflation) and output. To explain the impact on unemployment, I will be using the Phillips Curve. The Phillips Curve shows the relationship between inflation and unemployment. To explain the impact on the distribution of wealth, I will split people into two groups. One group continues to earn an income while the other does not.

Government intervention in response to Covid-19

The type of Government interventions and responses to Covid-19 should be consistent with the extent of that Government’s role in their country’s economy. A laissez-faire type of economy would rely on the economy is adjust by itself to the pandemic. A command type of economy would rely entirely on the Government to keep the economy running. Most economies fall somewhere between laissez-faire and command. Therefore, the type and extent of responses could vary quite considerably.

In Part 4, I discussed eleven Government intervention strategies to respond to the pandemic. In Part 5, I will group them broadly into five types. These intervention strategies have been categorised as:

- Do nothing

- Broad support for businesses

- Broad support for people

- Targeted support for vulnerable and small businesses and the self-employed

- Targeted support for vulnerable people.

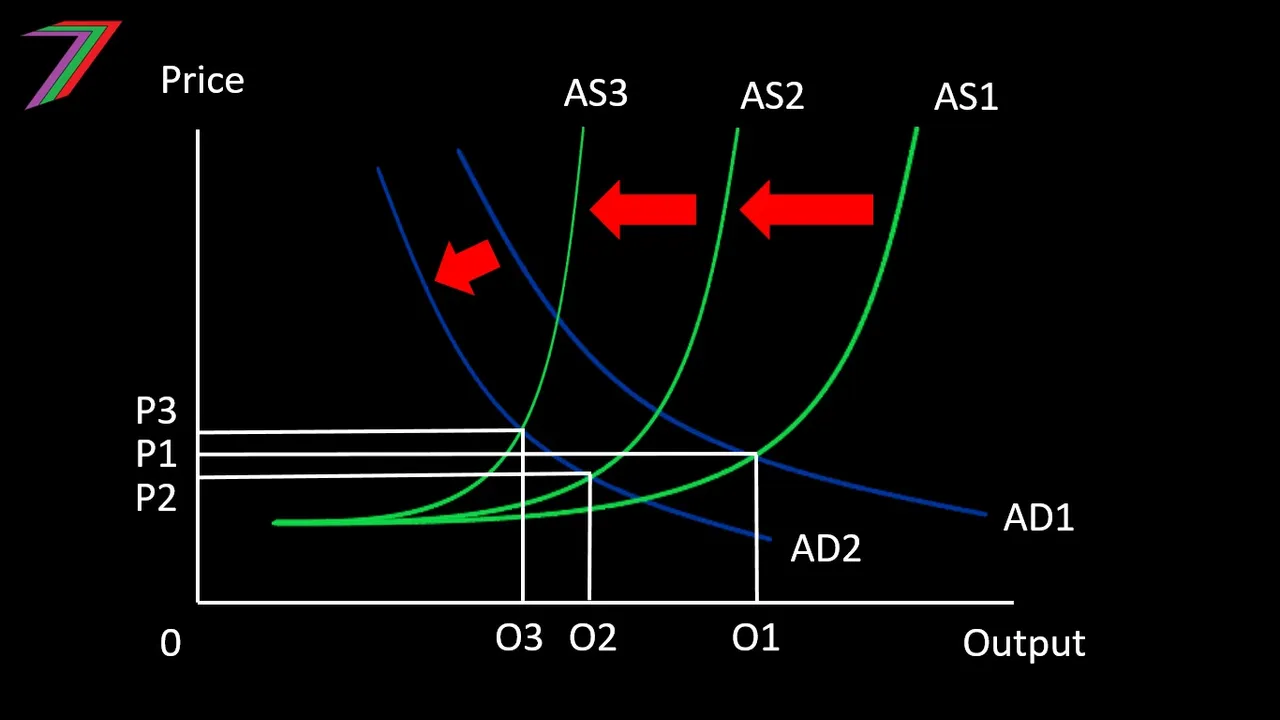

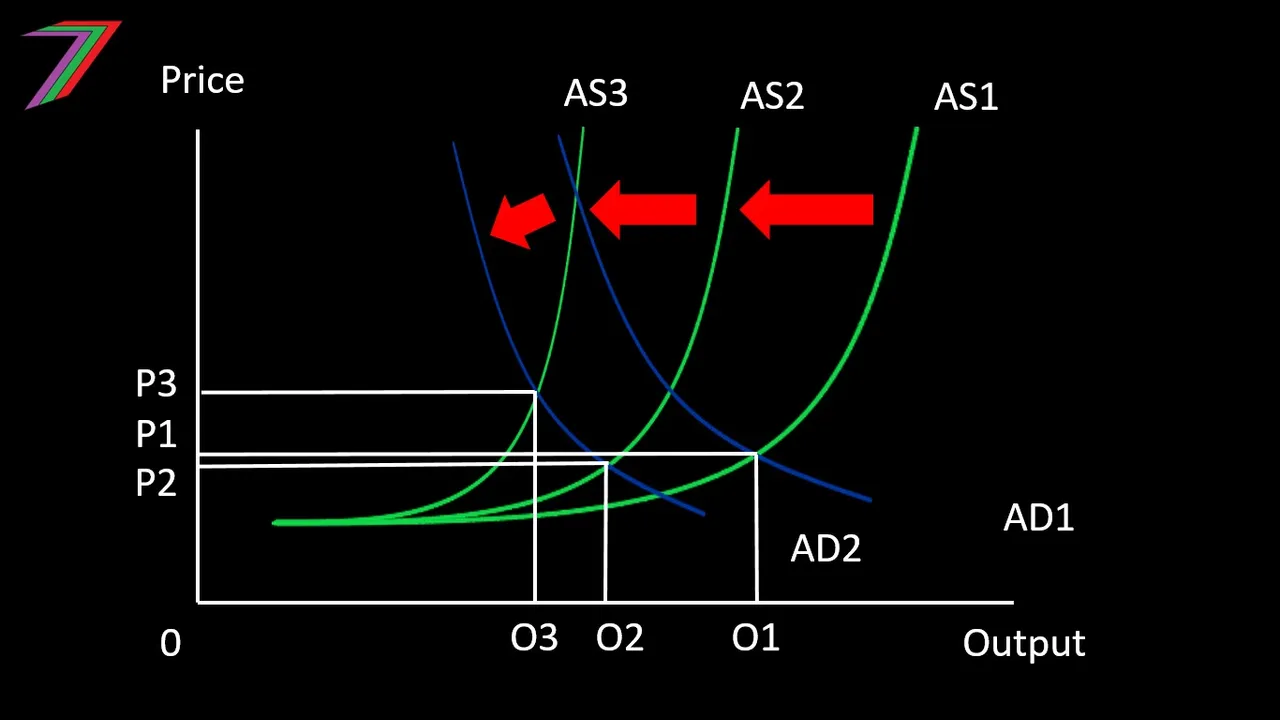

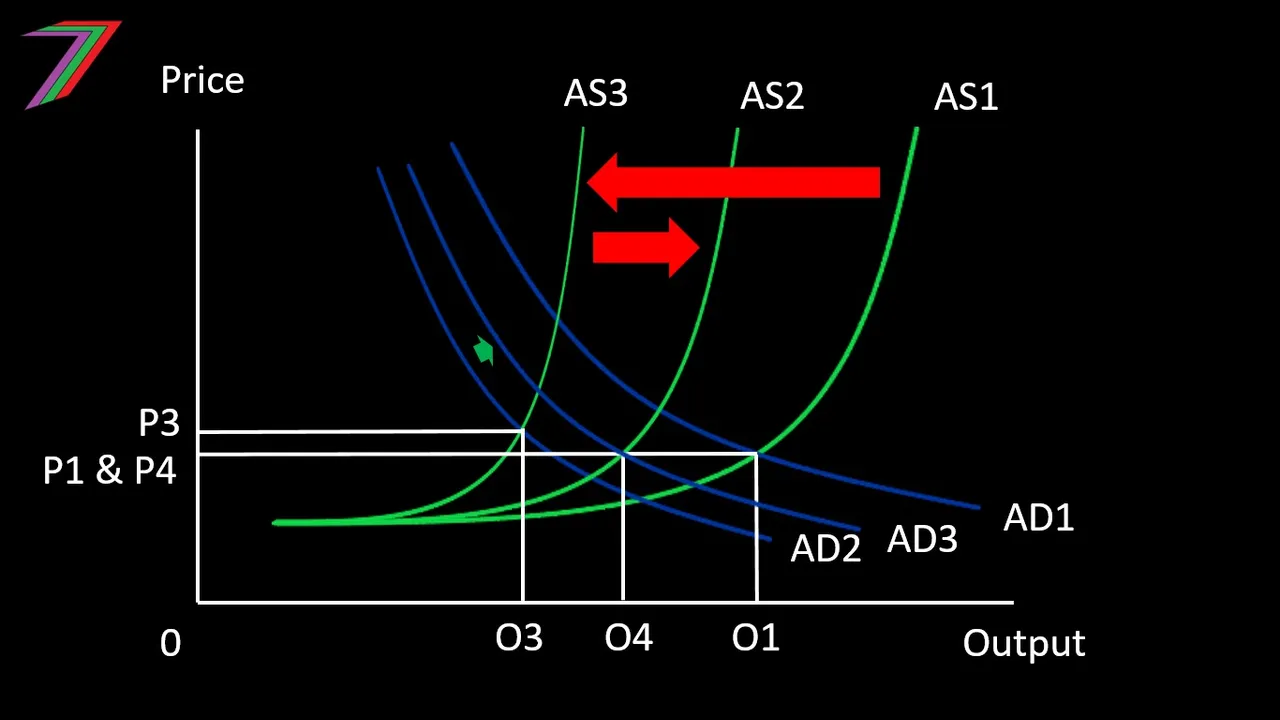

The ‘do nothing’ strategy will also act as the base (i.e. starting point) for the analysis of the other Government intervention strategies. Figure 1 contains a ‘do nothing’ strategy in the short-run.

Figure 1: Initial impact on the economy from Covid-19

Where O, P, AD, and AS are output, price, aggregate demand, and aggregate supply respectively.

Aggregate demand and aggregate supply will both decrease because of Covid-19 and the measures used to combat it. It is unclear, which will be greater, the decrease in aggregate demand or the decrease in aggregate supply. Figure 1 contains two aggregate demand curves and three aggregate supply curves. AD1 and AS1 are the aggregate demand and aggregate supply curves prior to Covid-19. AD2 is the aggregate demand curve as a response to Covid-19 and the measures taken. AS2 is the aggregate supply curve if aggregate supply is less effected by Covid-19 than aggregate demand. AS3 is the aggregate supply curve if aggregate supply is more effected by Covid-19 than aggregate demand. In both cases output falls. If aggregate demand is more effected than aggregate supply, price will fall (deflation). If aggregate supply is more effected than aggregate demand, price will increase (inflation).

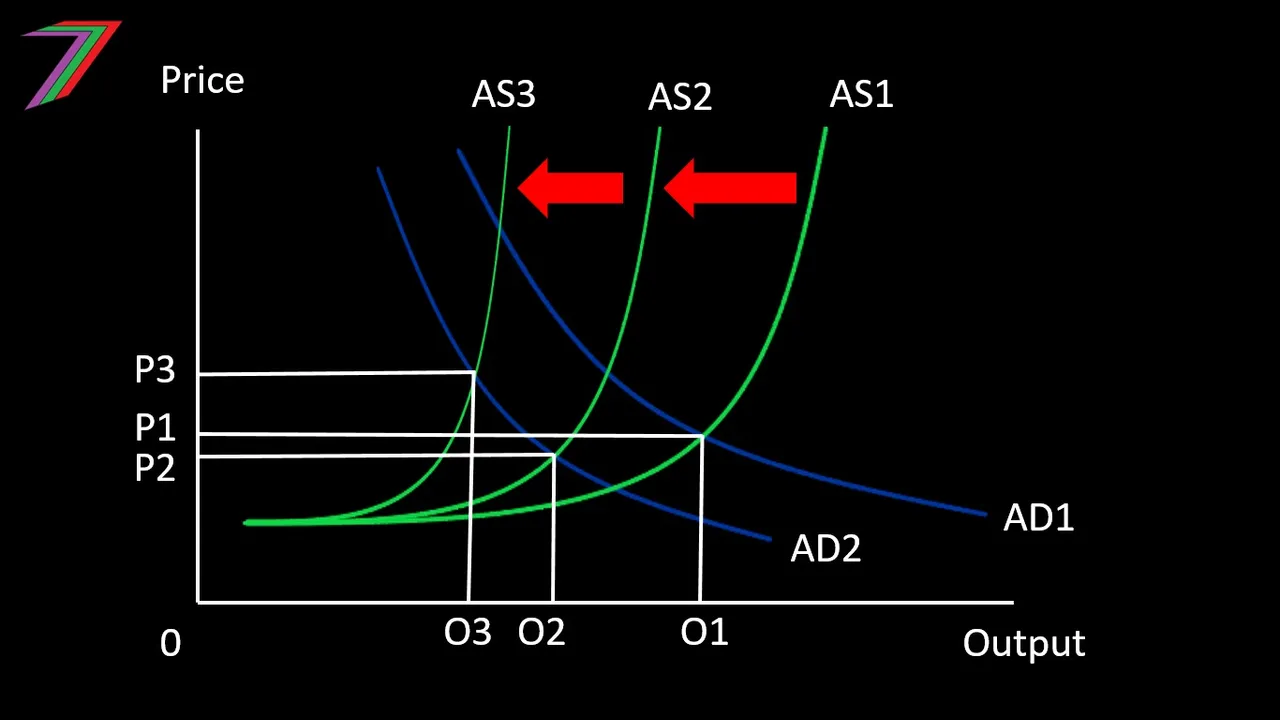

The extent of the fall in output as well as the extent of inflation or deflation depends on how much spare capacity the economy has prior to Covid-19. It is likely that some economies were operating close to capacity while other economies had spare capacity. Figure 2 contains aggregate demand and aggregate supply of an economy operating close to full capacity (i.e. full employment of resources) while experiencing some inflation.

Figure 2: Economy operating close to full employment

The impact on price is expected to be greater; this is because aggregate supply is relatively more inelastic as the economy does not have the resources to increase supply to meet demand. If aggregate demand is more effected than aggregate supply, this economy is likely to experience more deflationary pressure. If aggregate supply is more effected than aggregate demand, this economy is likely to experience more inflationary pressure.

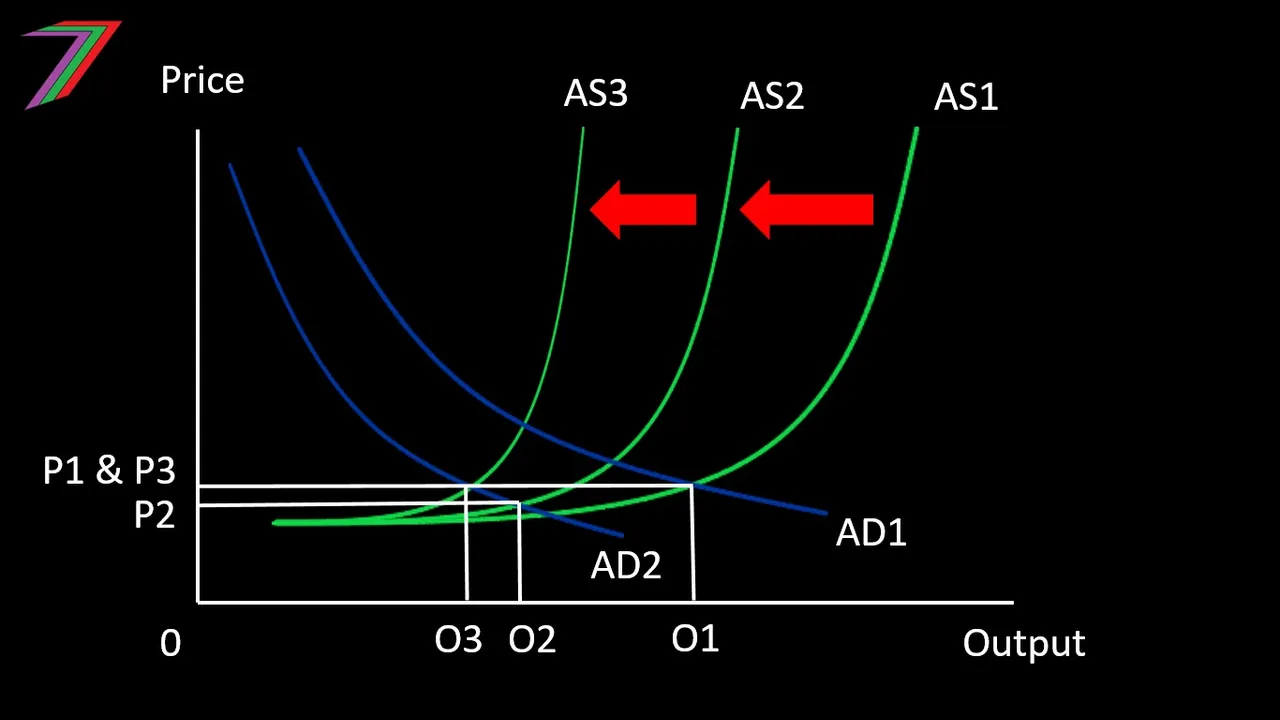

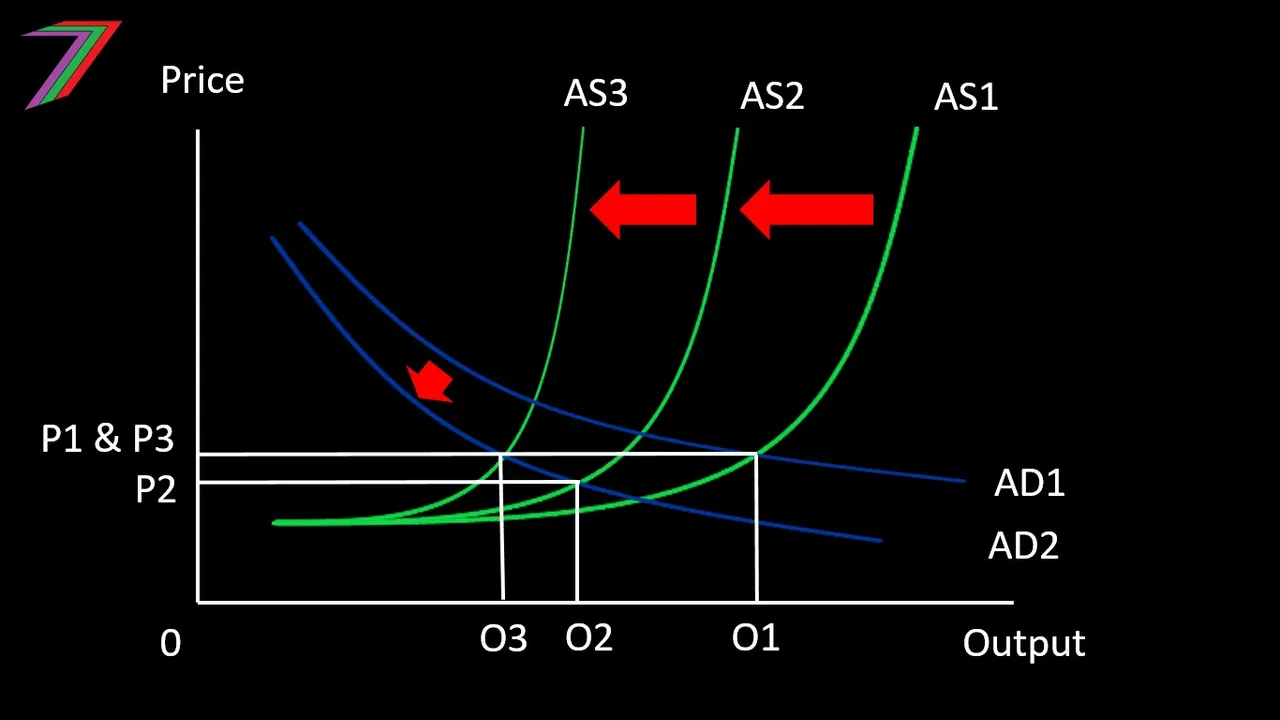

Figure 3 contains aggregate demand and aggregate supply of an economy operating with spare capacity (i.e. below full employment of resources).

Figure 3: Economy operating below full employment of resources

The impact on price is expected to be minimal; this is because aggregate supply is relatively more elastic as the economy has resources to increase supply to meet demand.

Another factor that influences the impact changes in aggregate demand and aggregate supply have on price and output is the elasticity of aggregate demand. Figure 4 contains a more inelastic demand and Figure 5 contains a more elastic demand.

Figure 4: Inelastic Aggregate Demand

Figure 5: Elastic Aggregate Demand

A fall in aggregate demand and aggregate supply will have a greater impact on price as demand becomes more inelastic. However, output could decrease by more if aggregate demand is elastic.

Broad support for businesses

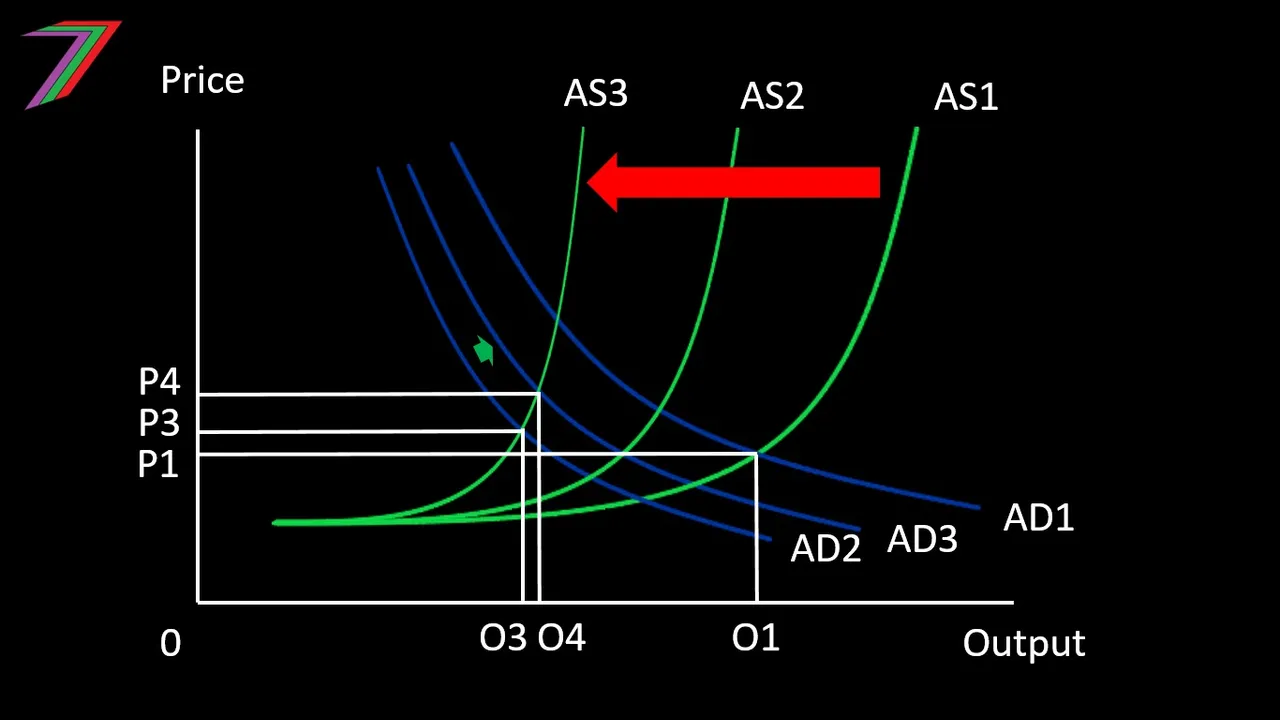

For the purpose of this post, I have assumed the base model to be Figure 1 with an aggregate supply (AS3) and aggregate demand (AD2). I am assuming that aggregate supply is more effected by the pandemic than aggregate demand.

Broad comprehensive support for businesses will increase demand if only a few employees are laid-off. I would also expect aggregate supply to increase if most businesses are able to reopen. Aggregate demand will increase by more than aggregate supply. This is because much of the demand generated will be from either grants or loans. However, supply will not be able to increase as quickly as some firms will have reduced capacity and higher costs. Figure 6 contains a short to medium run analysis of changes in price and output from broad support for business.

Figure 6: Impact on price and output from broad support for business

I would expect output to increase but not to return to the level prior to the pandemic. As aggregate demand would increase by more than aggregate supply, there will be pressure on price to increase. The extent of the inflation will depend on how the stimulus package was funded. Funding from increased money supply would be more inflationary than funding from tax.

In the long-run, I would expect the economy to struggle greatly as businesses would need to repay loans or pay higher taxes to cover the support they received during the pandemic.

Broad support for people

Broad support for people would increase demand, as people would have more money available to spend. However, direct support for people rather than businesses will still result in many businesses failing. Small businesses and businesses most badly hit by the pandemic and the measures to combat the pandemic are likely to fail. Many larger businesses are likely to survive because of the extent of their resources as well as the additional demand. I believe it is unlikely there will be any significant increase in aggregate supply in the short and medium run. This will put significant pressure on price and we are likely to see significant inflation not long after the pandemic is resolved. Figure 7 contains a short to medium run analysis of changes in price and output from broad support for people.

Figure 7: Impact on price and output from broad support for people

In the long-run, aggregate supply is likely to increase because higher demand is likely to enable businesses to increase operations and also offer incentive for new businesses to enter. Reduced competition from business failures could lead to higher prices and less efficiency, thus hindering the growth of aggregate supply. The pandemic is likely to create a survival of the biggest rather than survival of fittest.

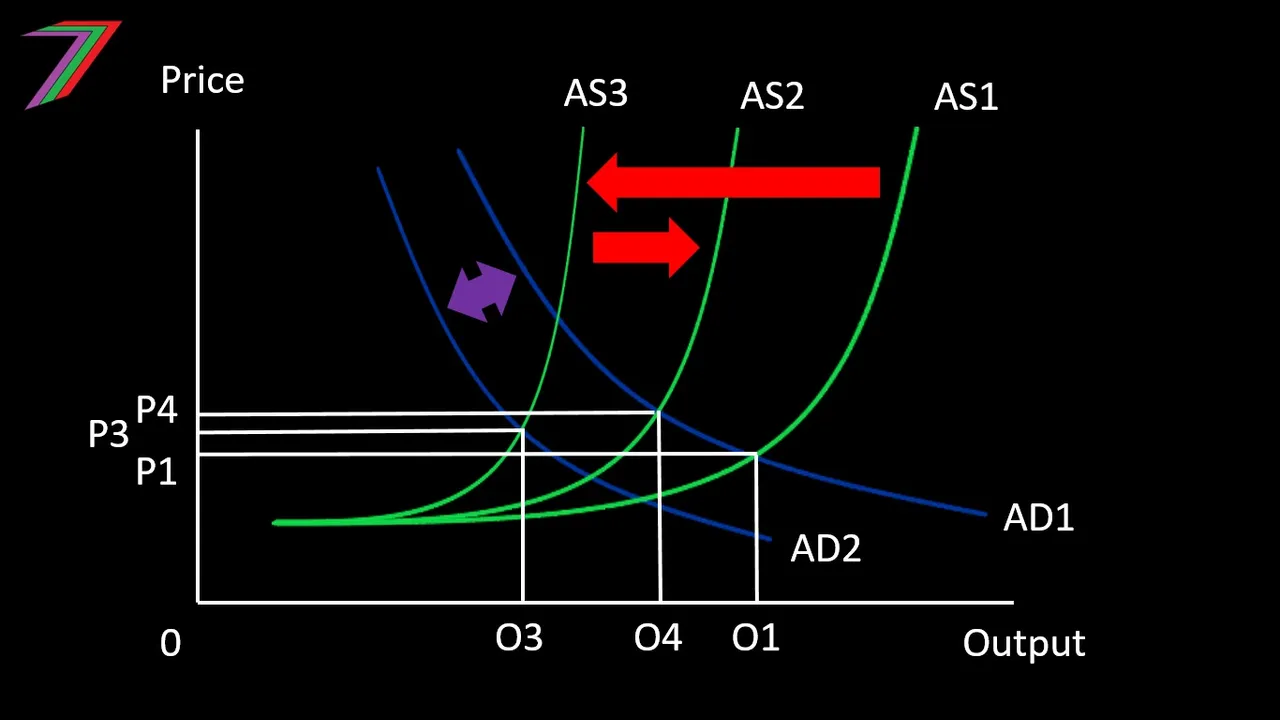

Targeted support for vulnerable and small businesses as well as the self-employed

Targeted support for vulnerable or small business should create a small increase in demand, as the people working in these areas will still have an income to spend. However, businesses that did not receive support are still likely to lay-off many employees. Aggregate supply can be expected to increase as vulnerable and small businesses will still be able to operate and therefore be able to respond to the increase in demand. Many businesses that are not supported should also be able to operate and contribute to production. Aggregate supply will not increase to the extent it was prior to the pandemic as businesses will not be able scale up immediately. Figure 8 contains a short to medium run analysis of changes in price and output from targeted support for vulnerable and/or small businesses and the self-employed.

Figure 8: Impact on price and output from targeted support of businesses

Output can be expected to increase as both aggregate demand and aggregate supply increase. The increase in aggregate supply is likely to be greater than the increase in aggregate demand; this should put downward price on price and reduce inflation. If the stimulus package is funded by increasing money supply, there could still be some upward pressure on price.

In the long-run, the economy is likely to be on the path to recovery. As businesses start hiring back employees both demand and supply will increase. Eventually the economy could return to normal.

The success of the targeting businesses strategy lies in the criteria used to determine which businesses to support and by how much. Too little support for too few businesses could result in many businesses to still failing, this would lead to a similar scenario as a ‘do nothing’ strategy. Too much support would lead to protecting many businesses but at a cost that would hinder growth in the long-run.

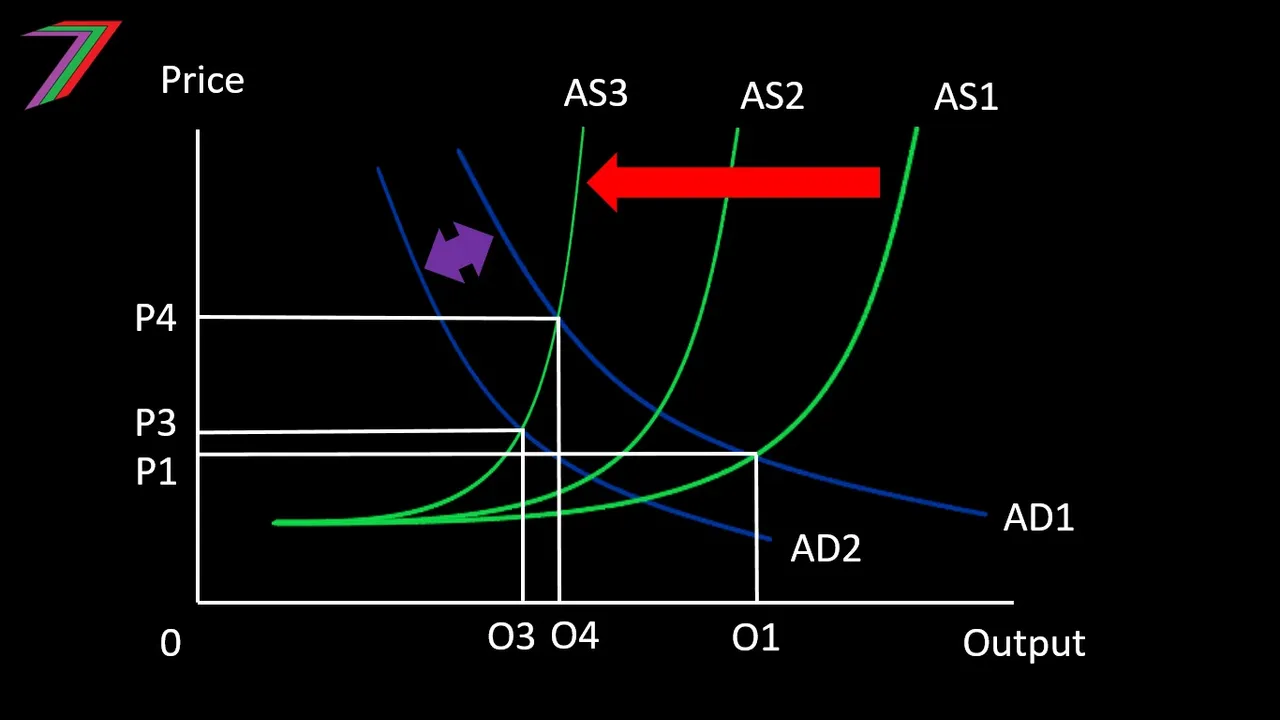

Targeted support for vulnerable people

Targeted support for just vulnerable people (i.e. low-income employees and self-employed) should increase aggregate demand slightly as the supported group will be generating some demand. Aggregate supply is unlikely to change. Small and vulnerable businesses are still likely to fail. Other businesses are still likely to lay-off workers and not be able to increase supply. Targeted support for just vulnerable people would have a similar affect to the ‘do nothing’ strategy but will reduce the extent of the hardship to the most vulnerable people. This strategy would not stimulate the economy. Figure 9 contains a short to medium run analysis of changes in price and output from targeted support for vulnerable people.

Figure 9: Impact on price and output from targeted support of businesses

In the long-run, the market will determine the extent of the recovery. Long-run recovery will not be hindered by increased debt or inflation from increased money supply. Many small and medium businesses would have failed because they did not have sufficient resources to survive. The recovery is likely to be led by larger businesses. This is likely to make the market less competitive than prior to the pandemic.

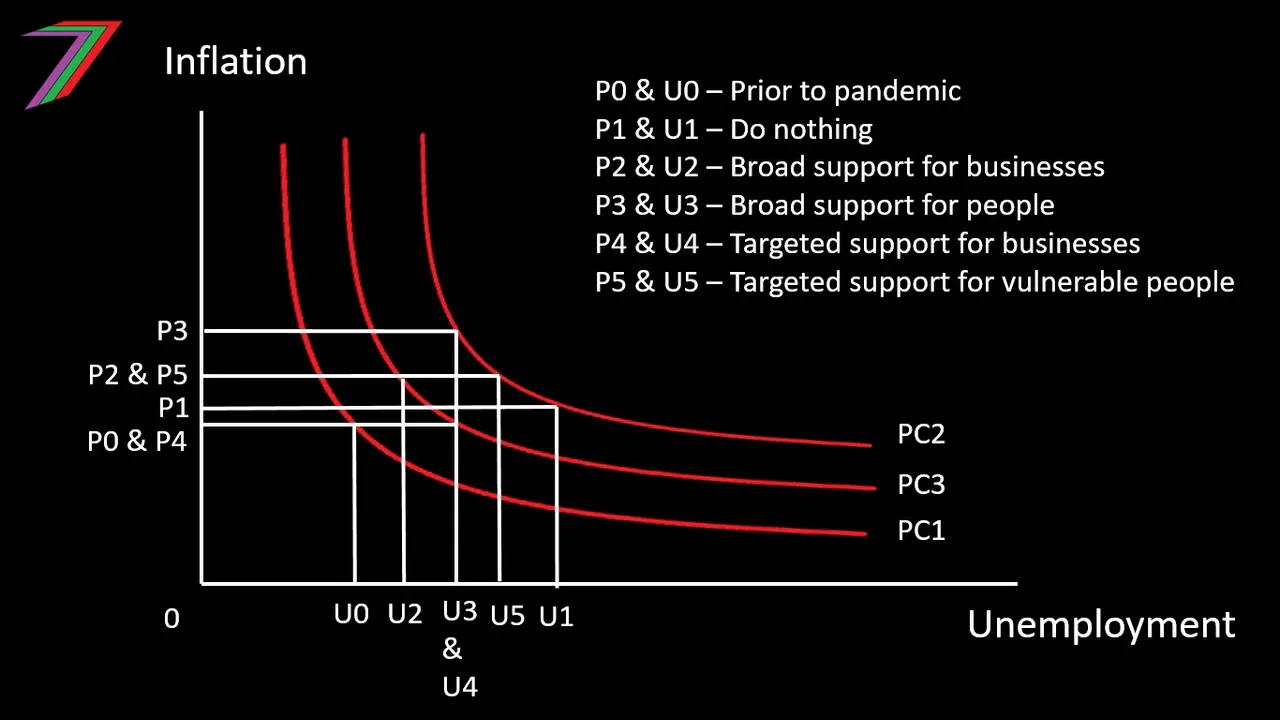

Unemployment and Inflation

Unemployment and inflation can be analysed using the Phillips Curve. The Phillips Curve shows the relationship between unemployment and inflation. An increase in aggregate demand reduces unemployment but increases inflation. As the economy approaches full employment, inflationary pressure increases. Likewise, an increase in aggregate demand increases unemployment but decreases inflation. Changes in aggregate supply causes shifts in the Phillips Curve. An increase in aggregate supply could reduce unemployment as well as decrease inflation.

For my analysis of inflation and unemployment, I have included all the strategies in the same diagram so that a comparison can be made. See Figure 10 below.

Figure 10: Analysis of unemployment and inflation of economic strategies

Where U, P, and PC are unemployment, price, and Phillips Curve receptively.

The analysis in Figure 10 is of the short-run to medium-run after the pandemic. All strategies will result in higher unemployment and most strategies will result in higher inflation. I have assumed P0 and U0 are inflation and unemployment prior to the pandemic. The pandemic and responses to the pandemic will cause aggregate demand to fall, thus causing a movement along the Phillips Curve such that unemployment increases and inflation decreases. However, aggregate supply also falls, thus causing the Phillips Curve to shift up to PC2. The outcome is higher unemployment and higher inflation. In the short and medium run, this would also be the outcome of a ‘do nothing’ strategy. In the short and medium run, the ‘do nothing’ strategy would result in the highest unemployment but the increase in inflation is likely to be minimal. Providing broad support for businesses would likely result in the smallest increase in unemployment but would also increase inflation by more than the ‘do nothing’ strategy. Providing broad support for people can be expected to create the most inflationary pressure of the five strategies whilst still resulting in substantial unemployment. Providing targeted support for businesses may not cause any inflation but would still result in substantial unemployment. Providing targeted support for vulnerable people would produce a similar outcome to doing nothing, unemployment would remain high and there would be slight inflationary pressure.

Comparing funding models

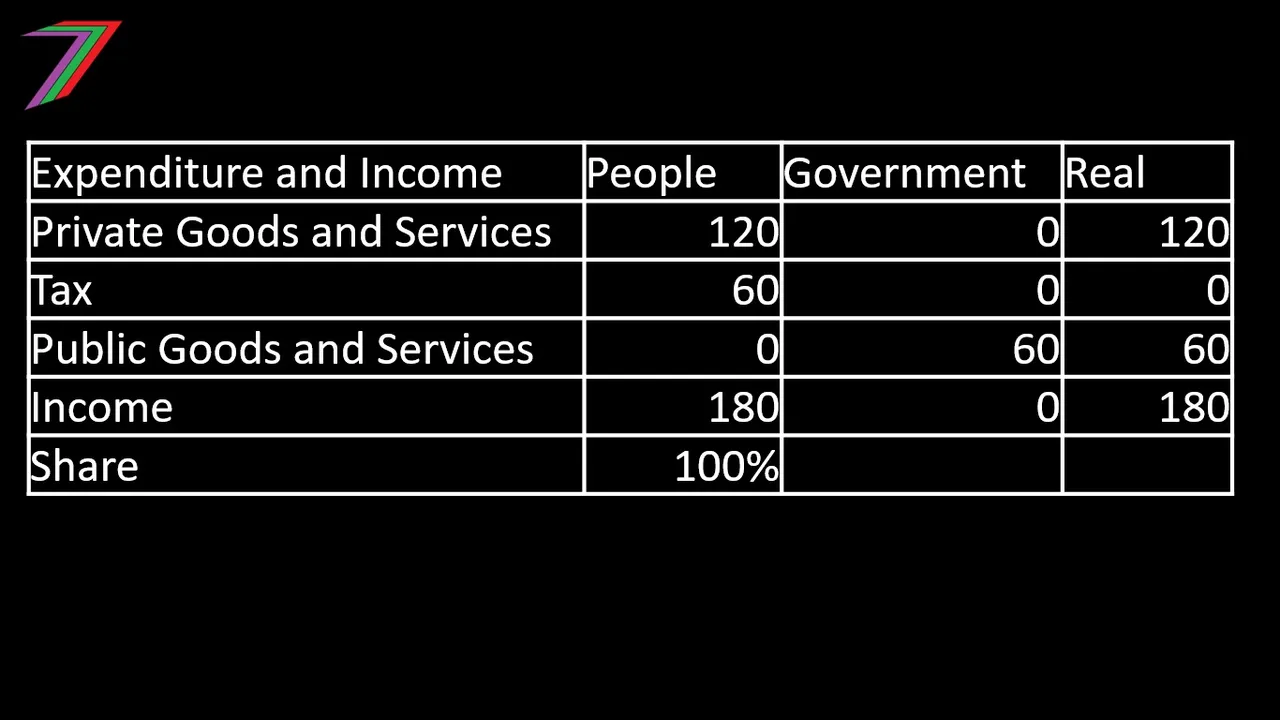

There are several ways a Government could fund their expenditure. These are outlined in Part 4 of this series. In short, Government expenditure is funded either directly by tax, borrowing, which is future tax revenue, or from increased money supply, which is paid through inflation. I would like to explain these funding models using very basic examples, which are populated with hypothetical numbers to demonstrate how they operate. Funding directly by tax is described in Table 1.

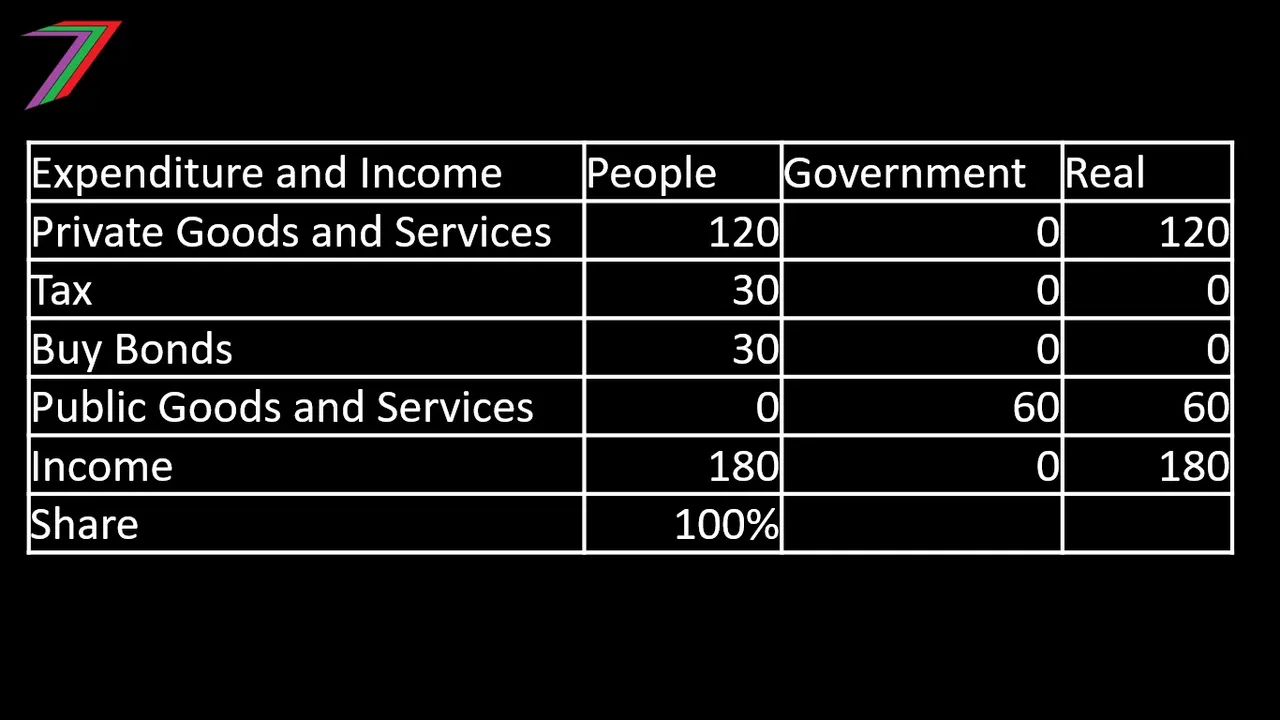

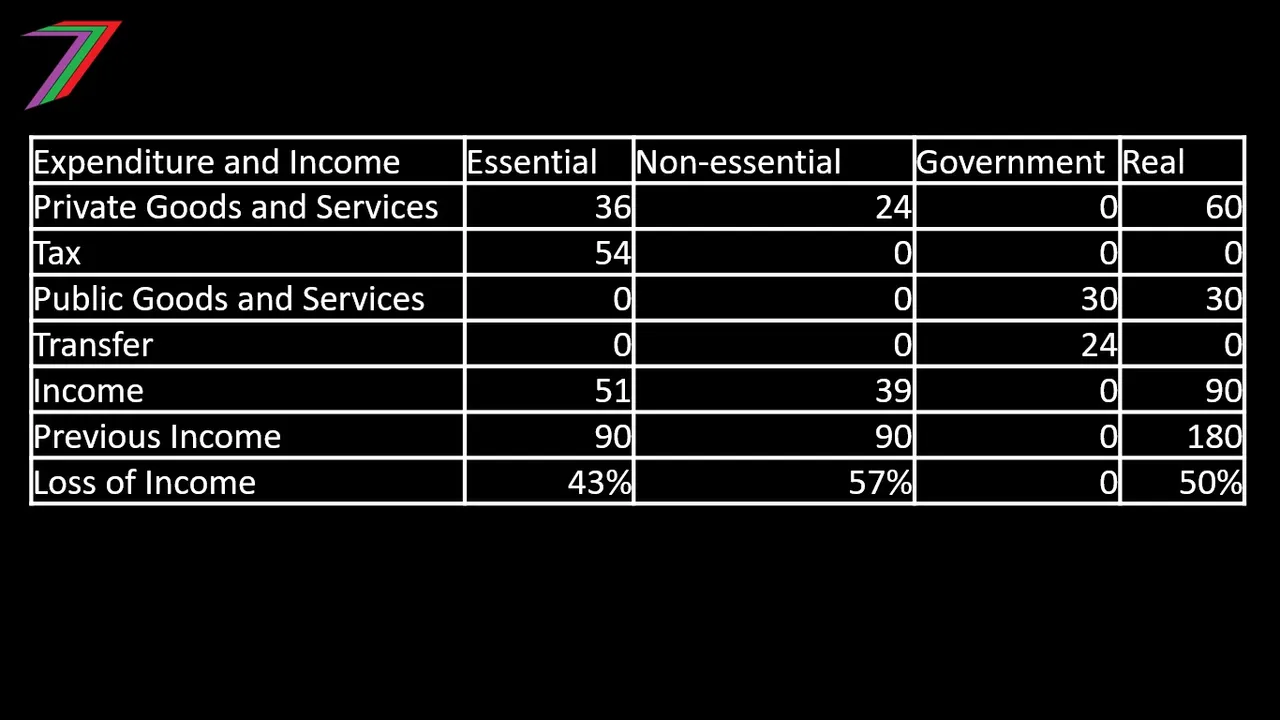

Table 1: Tax funded expenditure (very simple model)

This is a very simple model where people earn an income. They pay part of this income to the Government. The Government spends this income to provide public or merit goods. The people benefit from their own expenditure as well as expenditure by the Government. This funding model does not add inflationary pressure (i.e. real and nominal income are the same).

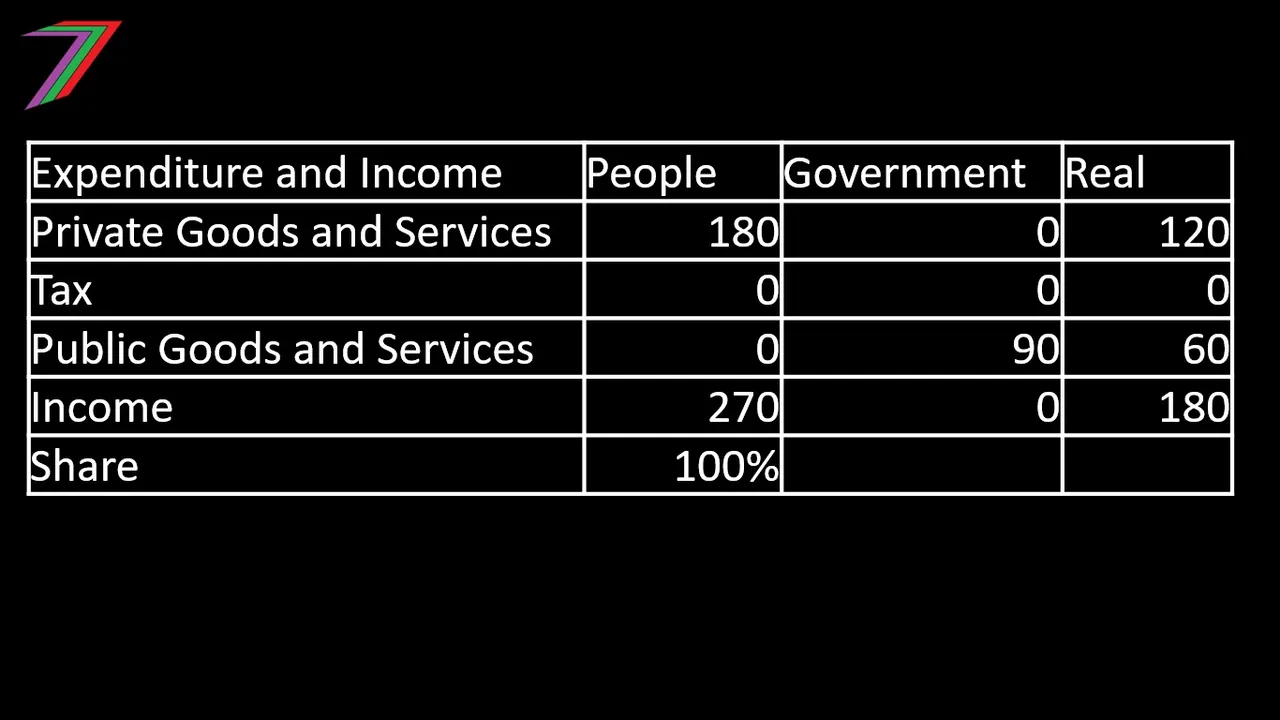

Funding by Government bonds is described in Table 2.

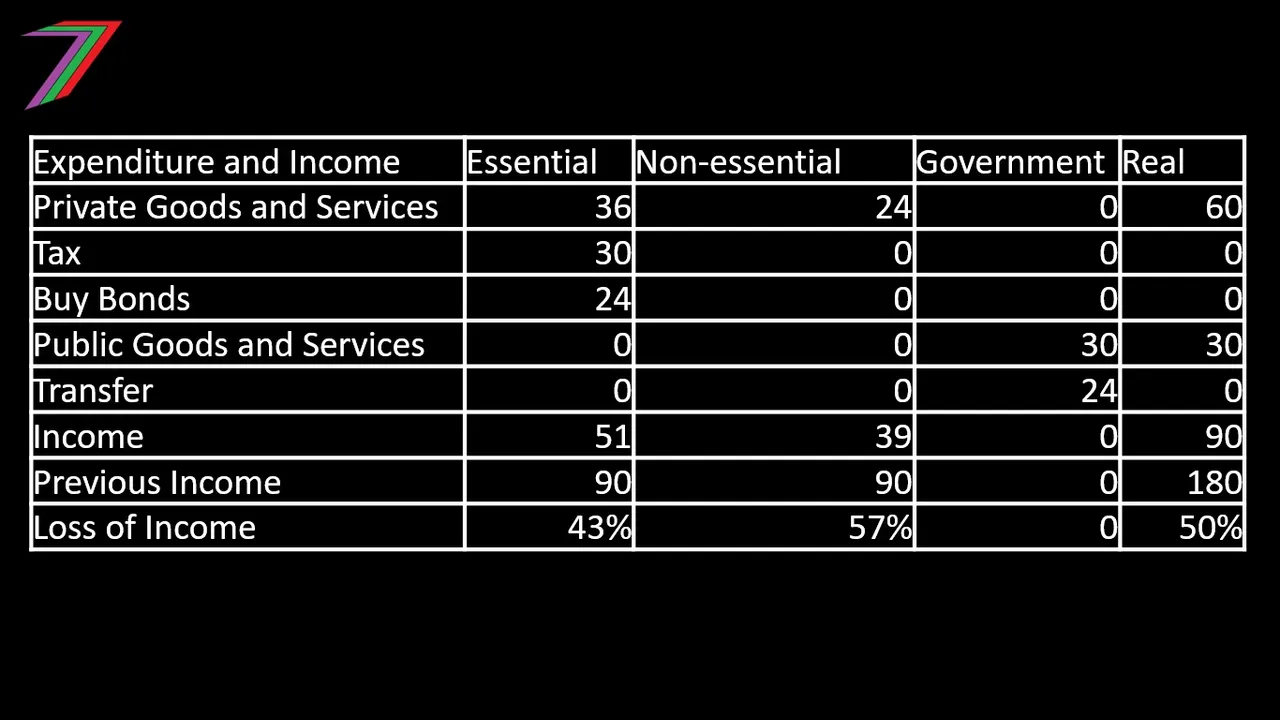

Table 2: Expenditure funded by bonds (very simple model)

The Government could reduce the immediate tax burden on society by selling bonds (i.e. borrowing). The money from the sale of bonds can be used to fund some of their expenditure. If the output of the country grows, tax revenue will increase with income, therefore, tax rates may not need to be increased to cover the cost of the borrowing. However, if the economy has a downturn, repaying the debt and interest becomes more difficult. This is one of the reasons why Governments intervene to prevent downturns. Stretching the natural economic business cycle is one of the reasons that many economies are very vulnerable, see Part 2 of this series, which discusses the vulnerability of economies.

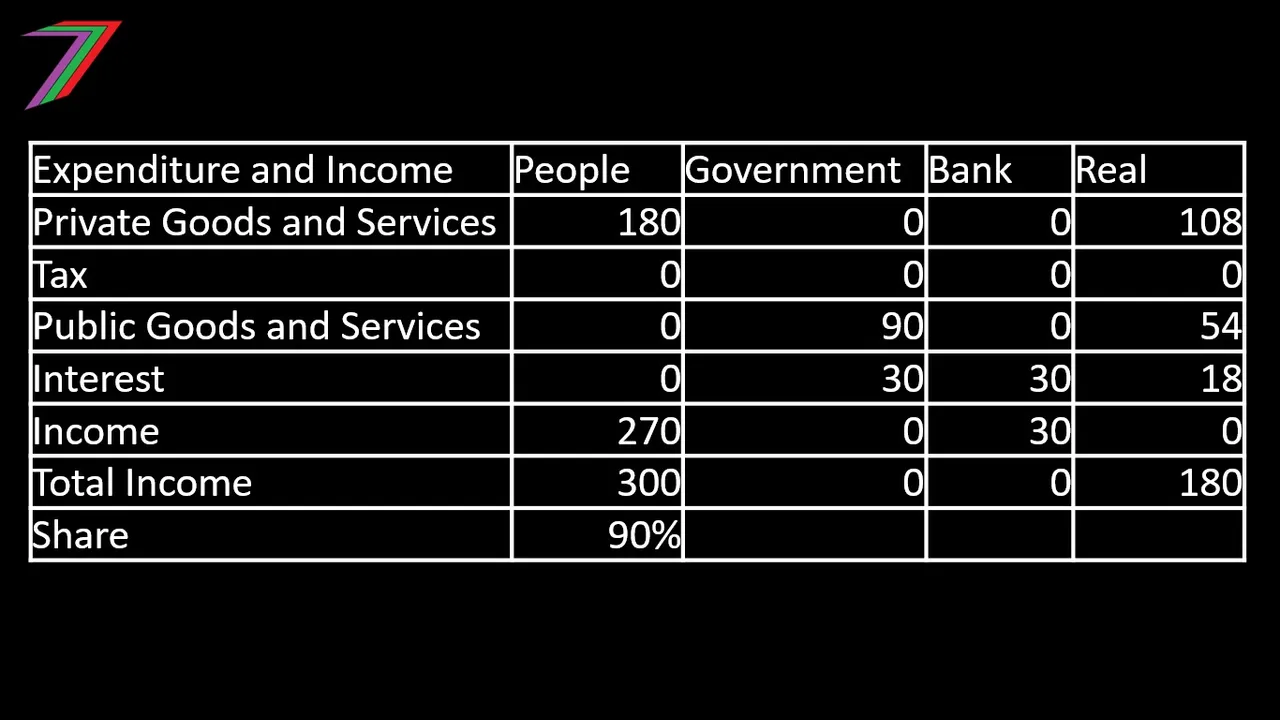

Funding by increasing money supply is described in Tables 3 and 4.

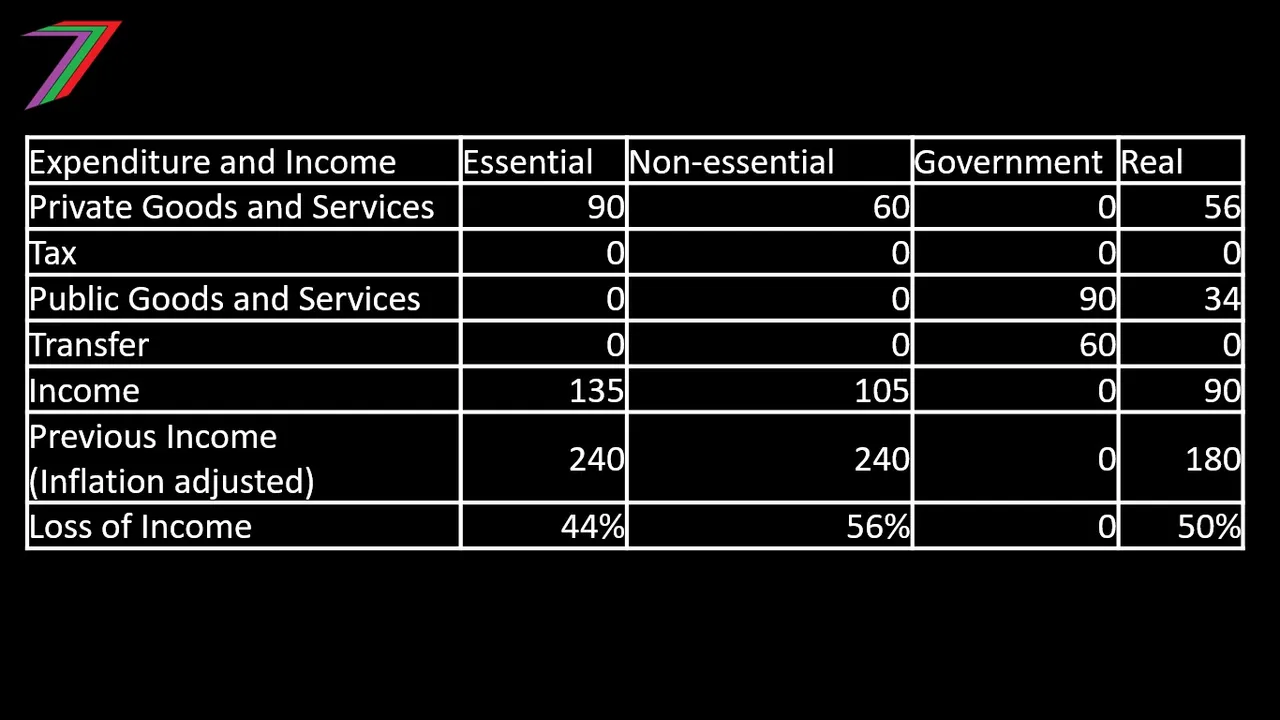

Table 3: Expenditure by increasing money supply (very simple model)

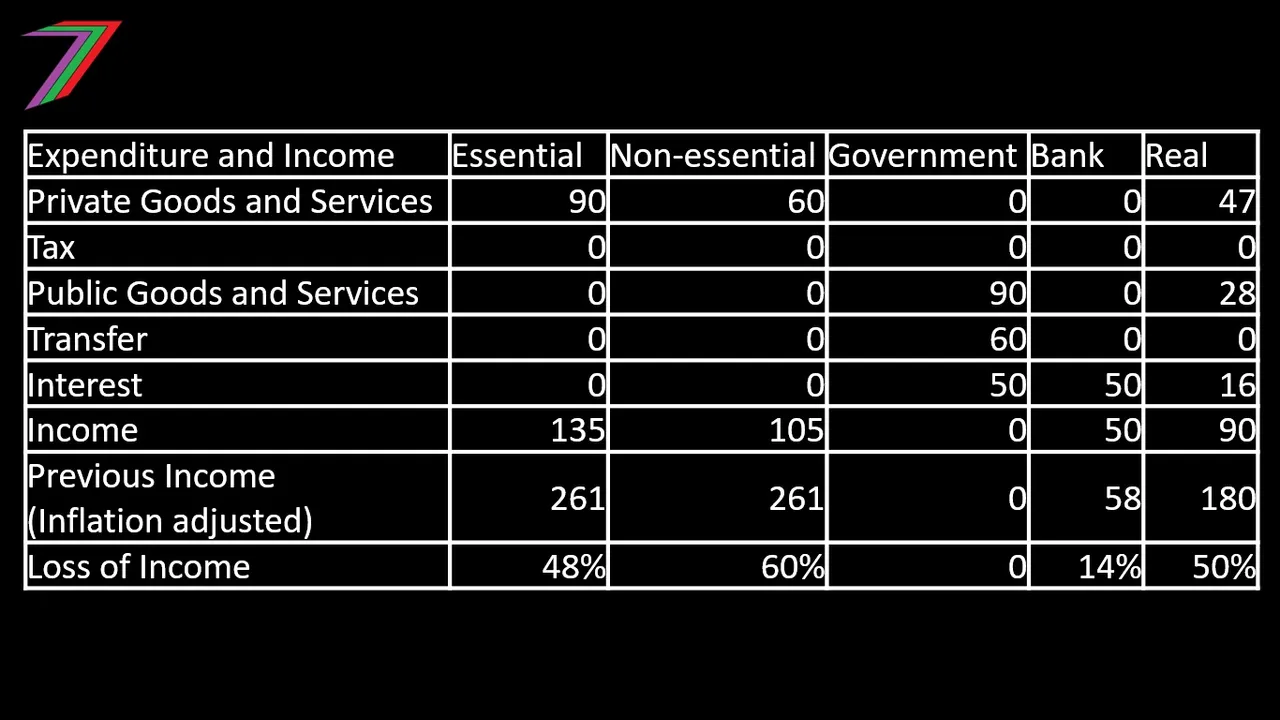

Table 4: Expenditure by increasing money supply includes interest

This is a very simple model where people earn an income. The people do not need to pay any tax; they can use their entire income to buy goods and services. The Government fund their own expenditure from newly created money. The people and the Government are forced to compete to obtain a limited supply of goods and services. This pushes the price of goods and services higher. The quantity of goods and services obtained by the people is the same in both models.

In the real world, it is much more complicated but the above explained logic remains the same. More money does not equate to more wealth. To generate more wealth requires greater provision of goods and services at a lower real cost. Real refers to the factors of production consumed such as land, labour, and capital and is not expressed in nominal dollars.

Funding through taxes and funding through increased money supply can encourage different types of behaviour. For example, taxes disincentivise producing output as profits and earning are taken to fund public goods and services. For example, increasing money supply disincentivises savings, as future higher prices erodes the value of savings and reduces interest rates

How did these different models affect the impact of Covid-19 strategies?

For the purpose of this post, I have divided the population into essential workers who can continue earning and non-essential workers who are not able to earn. A tax-based support system would require the people earning to support the people who are not able to earn. For this to be possible, the people earning would need to be taxed considerably more than previously. See Table 5.

Table 5: Tax those earning to support those not earning

This model would not be possible as the immediate tax burden would be too great for those still earning an income. Instead of taxing, the Government could sell bonds to those earning still earning an income. See Table 6.

Table 6: Sell bonds to those earning to support those not earning

Selling bonds raises money like a tax but the burden of the tax, as it will be collected later, could be spread over more people rather than just those with an income during the period of the pandemic. This has less of a wealth redistribution effect.

Considering the likely magnitude of many of the Government intervention strategies, raising money from the sale of bonds will not be sufficient.

Expenditure supported by increasing money supply does not require any money from those that are still able to earn or have savings. Instead, expenditure is supported by newly created money. Typically, this money would be supplied by the country’s Central Bank. See Tables 7 and 8.

Table 7: Government supporting those not earning with newly created money

Table 8: Government supporting those not earning with newly created money including interest payments

As explained earlier, the cost of the Government support will be paid in inflation and interest payments. The cost of inflation may not be felt immediately but eventually too many dollars will be chasing too few goods and services. High interest payments will also drain the economy and will either cost more in taxes or in terms of reduced expenditure on public and merit goods by the Government. Increasing money is also likely to put downward pressure on the price of the currency in foreign exchange markets, as interest rates will be relatively lower. Because of these reasons, increasing money supply is likely to have the most negative long-run impact on the economy. Despite these negative aspects, increasing the money supply will be the option chosen by most Governments because it is the fastest way to obtain the money necessary to deliver the proposed strategies.

Summary

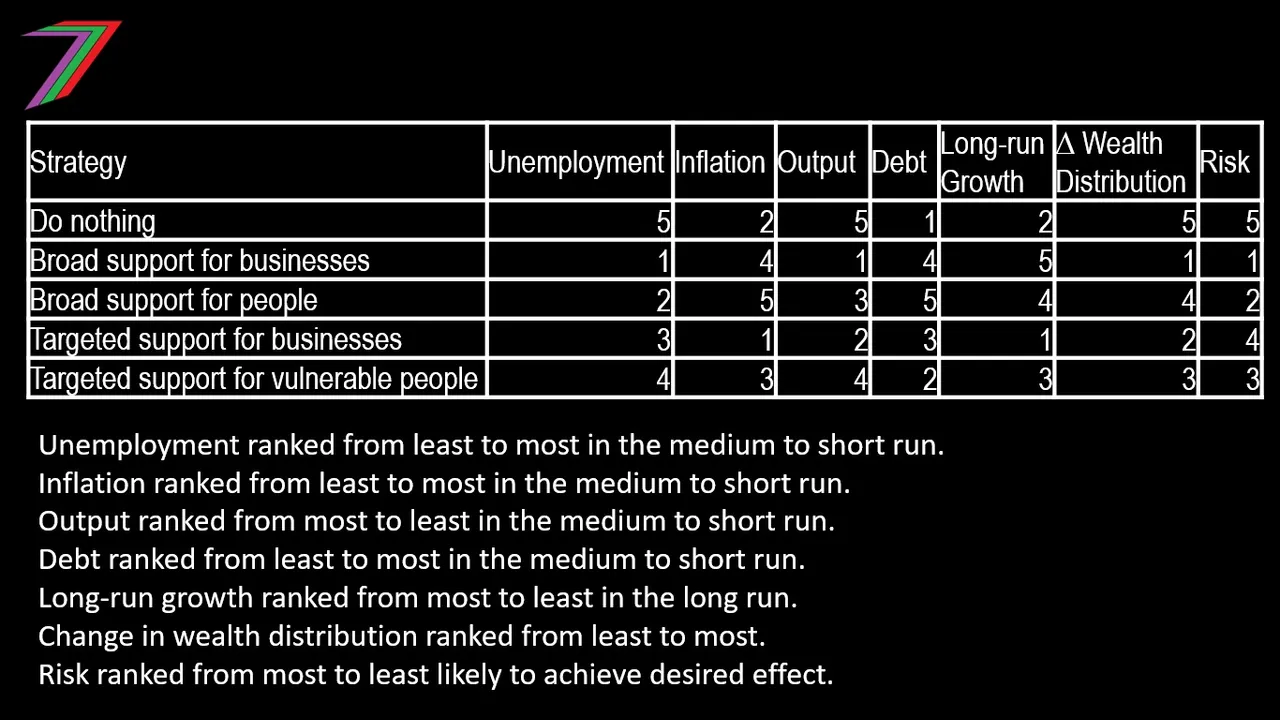

In this post, I have looked at the possible impact Government interventions and strategies could have on output, unemployment, inflation, wealth distribution and growth. In Table 9, I have summarised and ranked the impact of each of the strategies in respect to each other.

Table 9: Ranking Government interventions based on predicted impact on the economy

I have included an additional column for risk. Any strategy has some risk of failure and some level of unpredictability. For example, doing nothing could be considered high risk as the possible outcomes could range significantly. Whereas, offering the most support lowers risk, as people and businesses have the most resources available to survive. However, the lower risk strategies come at the highest cost.

Final Thoughts

This post has only very broadly analysed the possible impacts various strategies could have on the economy. It is likely that different strategies will be more effective for different economies. Countries that have more capacity (i.e. below full employment of resources) are likely to fair better with minimal business intervention because even if some businesses fail, the existing businesses will have the capacity to meet demand. Countries with minimal capacity will most likely need intervention to prevent too many businesses failing thus further reducing capacity.

I do not believe excessive Government intervention is a good path for any country. I believe the most vulnerable to the economic fallout of the crisis should be protected. I believe small businesses and self-employed should also be protected. I believe larger businesses even if they are vulnerable, such as airlines, should not be given any additional support. In Part 4, I discussed ‘too big to fail’ businesses. I did not analyse support for these businesses, as the basic models are not sufficient for any meaningful analysis. I do not believe the impact of these businesses failing would be as catastrophic as many economists and politicians claim.

In Part 6 of this series, I will be analysing the social impacts of Covid-19 and the responses to the pandemic. The post will focus on areas such as reduced freedom, domestic violence, impact of media, fearmongering, education and several others.

More posts

If you want to read any of my other posts, you can click on the links below. These links will lead you to posts containing my collection of works. These posts will be updated frequently.

Future of Social Media