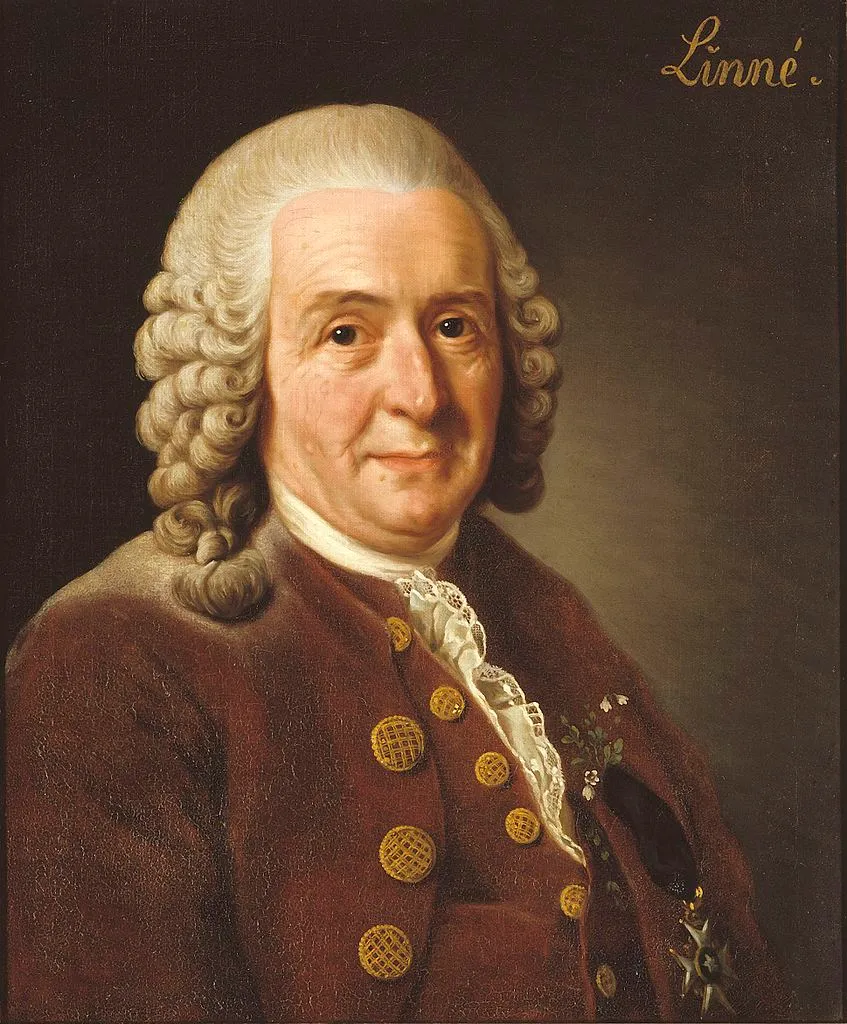

Since I was a small child I was curious about animals, especially about fishes. I was always reading and trying to find out as much as possible about them. When I moved from books for children to more serious stuff I discovered Latin names for species and they were always trailing L. or Linnaeus and some year behind them. At that time I didn't give much thought to it I just took it for something that just needs to be there. Since I am from Croatia I was firstly studying European freshwater fishes. Once when I started to broaden my horizons to different continents I started noticing D. and K. and whatnot trailing Latin names I decided to investigate the matter of trailing letters and then I found out about Carolus Linnaeus. In this article, I will try to present his life and work.

Early life

Linnæus was born in the village of Råshult in Småland, Sweden, on 23 May 1707. He was the first of five children in his family. His father Nills was an amateur botanist and a Lutheran priest.

Since an early age, he was showing interest in botany. Whenever he would throw a childish tantrum if he was given a flower he would immediately calm down. He even had his own patch in the garden of his family.

His father taught him basic of Latin, religion, and geography. At age of nine, he was sent to the Lower Grammar School at Växjö in 1717. Linnaeus didn't study much, he preferred going to the countryside to look for plants. He reached the last year of the Lower School when he was fifteen. His headmaster, who was interested in botany, put him in charge of his gardens. He also introduced him to the Johan Rothman, a state doctor of Småland and a teacher at the gymnasium in Växjö. Also a botanist, doctor broadened Linnaeus' interest in botany and helped him develop an interest in medicine. By the age of 17, Linnaeus had become well acquainted with the existing botanical literature.

Linnaeus enrolled in the Växjö gymnasium in 1724, where he studied a curriculum designed for boys preparing for the priesthood(Greek, Hebrew, theology, and mathematics). In the last year at the gymnasium, Linnaeus' father visited to ask the professors how his son's studies were progressing. Most of the teachers said that the boy would never become a scholar. The doctor believed otherwise and offered to have Linnaeus live with his family in Växjö and to teach him physiology and botany. Wich Linnaeus father accepted.

Later studies

At age of 21, Linnaeus enrolled at Lund University in Skane. Professor Kilian Stobæus, a natural scientist, physician and historian, offered Linnaeus tutoring and lodging, as well as the use of his library, which included many books about botany. He also gave the student free admission to his lectures.

In August 1728, Linnaeus started attending Uppsala University. In Uppsala, Linnaeus met a new benefactor, Olof Celsius, who was a professor of theology and an amateur botanist. He received Linnaeus into his home and allowed him to use his library, which was one of the richest botanical libraries in Sweden.

In 1729, Linnaeus wrote a thesis, Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum on plant sexual reproduction. This attracted the attention of professor Olof Rudbeck the Younger. in May 1730, he selected Linnaeus to give lectures at the University although he was only a second-year student. His lectures were quite popular with the audience of up to 300 people. In the winter of 1730, Linnaeus began to doubt the old system of classification and decided to create one of his own. His plan was to divide the plants by the number of stamens and pistils.

Doctorate in two weeks

In 1734 Linnaeus accepted an invitation from the student Claes Sohlberg to spend the Christmas holiday in Falun with Sohlberg's family. Sohlberg's father suggested to Linnaeus he should take Sohlberg to the Dutch Republic and continue to tutor him there for an annual salary. At that time, the Dutch Republic was the place to study natural history and a common place for Swedes to take their doctoral degree; Linnaeus, who was interested in both of these, accepted.

In April 1735, Linnaeus and Sohlberg set out for the Netherlands, with Linnaeus to take a doctoral degree in medicine at the University of Harderwijk. When Linnaeus reached Harderwijk, he began working towards a degree immediately. At the time, Harderwijk was known for awarding "instant" degrees after as little as a week. After he handed in a thesis on the cause of malaria and defended in a public debate. His dissertation was titled Dissertatio medica inauguralis in qua exhibetur hypothesis nova de febrium intermittentium causa ("Inaugural thesis in medicine, in which a new hypothesis on the cause of intermittent fevers is presented"). He concluded that malaria arose only in places where the soil is rich with clay. He is now known to have been wrong about the cause, not having a microscope good enough to see malarial parasites, which were spread by mosquitoes breeding in the water that collected in ruts and puddles.[ But he was right in predicting that traditional Chinese medicine, including the use of wormwood (Artemisia), is a potential source of antimalarial drugs. Artemisinins, derived from wormwood, are now the principal antimalarial drugs.

The next step was to take an oral examination and to diagnose a patient. After less than two weeks, he took his degree and became a doctor, at the age of 28.

Lifes work binominal nomenclature

One of the first scientists Linnaeus met in the Netherlands was Johan Frederik Gronovius to whom Linnaeus showed one of the several manuscripts he had brought with him from Sweden. The manuscript described a new system for classifying plants. He was very impressed and offered to help pay for the printing. With an additional monetary contribution by the Scottish doctor Isaac Lawson, the manuscript was published as Systema Naturae in 1735.

Linnaeus returned to Sweden in 1738 and began a medical practice in Stockholm. He practiced medicine until the early 1740s but always wanted to return to his botanical studies. A position became available at Uppsala University, and he received the chair in medicine and botany there in 1742. Linnaeus built his further career upon the foundations he had laid in the Netherlands. He used his international contacts to create a network of correspondents that provided him with seeds and specimens from all over the world. He then incorporated this material into the botanical garden at Uppsala, and these acquisitions helped him develop and refine the empirical basis for revised and enlarged editions of his major taxonomic works. During his lifetime he completed 12 editions of Systema Naturae, 6 editions of Genera Plantarum, 2 editions of Species Plantarum (“Species of Plants,” which succeeded the Hortus Cliffortianus in 1753), and a revised edition of Fundamenta Botanica (which was later renamed Philosophia Botanica [1751; “Philosophy of Botany”]).

Linnaeus’s most lasting achievement was the creation of binomial nomenclature, the system of formally classifying and naming organisms according to their genus and species. In contrast to earlier names that were made up of diagnostic phrases, binomial names (or “trivial” names, as Linnaeus himself called them) conferred no bias about the quality or value of plant species named. Rather, they served as labels by which a species could be universally addressed. This naming system was also implicitly hierarchical, as each species is classified within a genus. The first use of binomial nomenclature by Linnaeus occurred within the context of a small project in which students were asked to identify the plants consumed by different kinds of cattle. In this project, binomial names served as a type of shorthand for field observations. Despite the advantages of this naming system, binomial names were used consistently in print by Linnaeus only after the publication of Species Plantarum in 1753.

In his own lifetime, Linnaeus became something of an institution in himself, as naturalists everywhere had to address him directly or at least his work in order to determine whether specimens in their collections were indeed new species. The rules of nomenclature that he put forward in his Philosophia Botanica rested on a recognition of the “law of priority,” the rule stating that the first properly published name of a species or genus takes precedence over all other proposed names. These rules became firmly established in the field of natural history and also formed the backbone of international codes of nomenclature—such as the Strickland Code in 1842—created for the fields of botany and zoology in the mid-19th century. The first edition of Species Plantarum and the 10th edition of Systema Naturae from 1758 are the agreed starting points for botanical and zoological nomenclature, respectively.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Linnaeus

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Carolus-Linnaeus