Thursday, 12 October 2017

Welcome to Dispatches, a weekly summary of my writing, listening and reading habits. I'm Andrew McMillen, a freelance journalist and author based in Brisbane, Australia. (No 'sounds' again this week, though you can expect to see it next time.)Words:

I had a feature published on Backchannel last week. Excerpt below.

The Social Network Doling Out Millions in Ephemeral Money (2,000 words / 10 minutes)To read the full story, visit Backchannel. Above illustration credit: Lauren Cierzan.

Steemit is a social network with the radical idea of paying users for their contributions. But in the crypto gold rush, it's unclear who stands to profit.

Every time you log onto Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter to share a photo or post an article, you give up a piece of yourself in exchange for entertainment. This is the way of the modern world: Smart companies build apps and websites that keep our eyeballs engaged, and we reward them with our data and attention, which benefit their bottom line.

Steemit, a nascent social media platform, is trying to change all that by rewarding its users with cold, hard cash in the form of a cryptocurrency. Everything that you do on Steemit–every post, every comment, and every like–translates to a fraction of a digital currency called Steem. Over time, as Steem accumulates, it can be cashed out for normal currency. (Or held, if you think Steem is headed for a bright future.)

The idea for Steemit began with a white paper, which quietly spread among a small community of techies when it was released in March 2016. The exhaustive 44-page overview wasn't intended for a general audience, but the document contained a powerful message. User-generated content, the authors argued, had created billions of dollars of value for the shareholders of social media companies. Yet while moguls like Mark Zuckerberg got rich, the content creators who fueled networks like Facebook got nothing. Steemit's creators outlined their intention to challenge that power imbalance by putting a value on contributions: "Steem is the first cryptocurrency that attempts to accurately and transparently reward...[the] individuals who make subjective contributions to its community."

A minuscule but dedicated audience rallied around Steemit, posting stories and experimenting with the form to discover what posts attracted the most votes and comments. When Steemit released its first payouts that July, three months after launch, things got serious.

Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are only worth whatever value people ascribe to them, so there was no guarantee that the tokens dropping into Steemit accounts would ever be worth anything. Yet the Steem that rolled out to users translated to more than $1.2 million in American dollars. Overnight, the little-known currency spiked to a $350 million market capitalization–momentarily rocketing it into the rare company of Bitcoin and Ethereum, the world's highest-valued cryptocurrencies.

Today, Steem's market capitalization has settled in the vicinity of $294 million. One Steem is worth slightly more than one United States Dollar, and the currency remains a regular presence at the edge of the top 20 most traded digital currencies. It's a precipitous rise for a company that just 18 months ago existed only as an idea in the minds of its founders. More than $30 million worth of Steem has been distributed to over 50,000 users since its launch, according to company reports. It's too early to know whether Steemit can hold onto its users' interest and its market value. But its goal–upending a model built by social media giants over decades of use in favor of a more populist system–is significant in itself. By removing the middlemen and allowing users to profit directly from the networks they participate in, Steemit could provide a roadmap to a more equitable social network.

Or users could get bored or distracted by something newer and shinier and abandon it. The possibility of a popped bubble looms over every cryptocurrency, and the bubbles are filled with both attention and speculative investment. Steemit's value is based on money that its founders have virtually willed into existence. Fortunes could vanish at any moment, but someone stands to get rich in the process.

How I found this story: I have been watching Steemit with interest for more than a year, after I saw author and journalist Neil Strauss tweeting about it in mid-2016. I registered an account in August, introduced myself to the community in November, and began experimenting with posting on the site. For the most part, I've been sharing Dispatches on Steemit each week, as I think that's a good way to add value to the community. I've also occasionally posted excerpts from some of my published journalism – but without much success or interest in either case, to be honest. If you scroll back through my account, @andrewmcmillen, you'll see that most of my posts have attracted only a handful of votes, making each post worth a few cents apiece – hardly worth the time spent copying the HTML code across, you might conclude, and you might be right.

That all changed when I posted this Backchannel article on Steemit last week, though: the post where I shared an excerpt and linked to the full article currently has 1200+ votes from the community, and as a result, that post has been ascribed a value of more than USD$600. Will this mean anything in a year or two? I've no idea, but I am fascinated by this concept and community. I'm proud to have been among the first journalists to have explored and written about the community at length, and I'm interested to see how it evolves.

Reads:

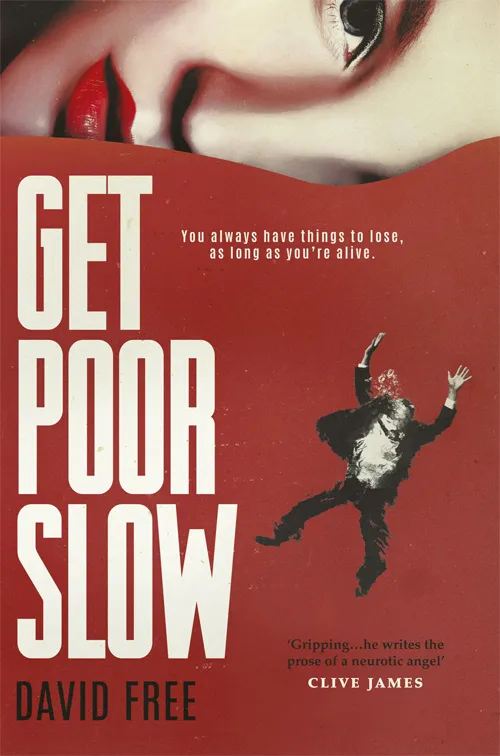

Get Poor Slow by David Free (2017, Picador). I hadn't come across a book featuring a protagonist who works as a newspaper book critic until I read Get Poor Slow, which also happens to be written by one of Australia's best newspaper book critics. Here, the fictional critic in question is Ray Saint, a broke and broken alcoholic, and a failed novelist who is known for tearing strips off practically everything his editor assigns him to review.

The novel begins with Saint under siege from the press, who are camped outside his house because he was the last person to see Jade Howe alive. She was a beautiful young publishing assistant who just so happened to wind up dead, soon after she and Saint had a brief fling. Did he do it, or has he been framed? This is the question that kept me turning pages and laughing often, as Ray Saint is among the darkest, funniest characters I've seen committed to the page.

Author David Free is primarily a reviewer for The Weekend Australian, and – full disclosure – that's where he favourably reviewed my book Talking Smack in 2014. I've reviewed quite a few books for that publication, too, and I greatly enjoyed the comic exaggeration he places on the diminishing role of literary critics who write for newspapers. Ray Saint loves classic literature and loathes the state of modern publishing, and his cynicism has earned him a poor reputation in the industry and a lack of wealth, too: the book's title is taken from an aside on page 130, where Saint notes, "I was getting poor much slower, before she came along."

I can't recommend this book highly enough, especially to anyone who works in publishing or the media. I think its real genius is that David Free has captured the voice of a writer who thinks he's much better than everyone else in the game, to the point where his prose reflects that opinion: at times, Saint self-consciously wonders whether he's already used a particular phrase earlier in the piece. His memory's fucked due to a childhood accident, and the booze and prescription painkillers he feeds his brain with probably aren't helping, either. Saint is the very definition of an unreliable narrator, and much of the story is devoted to trying to remember what really happened to Jade Howe. There's a great twist late in the piece, and the ending is wholly satisfying. I look forward to reading this for the second time, purely to savour the stark sharpness of Free's writing once again.

The Tech Insiders Who Fear A Smartphone Dystopia by Paul Lewis on The Guardian (4,700 words / 23 minutes). When some of the individuals who worked on the social media tools that keep us coming back to these sites start opting out of the websites they helped popularise, it might be time to reconsider how the rest of us are spending our time online. Says one designer: "Smartphones are useful tools, but they're addictive. Pull-to-refresh is addictive. Twitter is addictive. These are not good things. When I was working on them, it was not something I was mature enough to think about. I'm not saying I'm mature now, but I'm a little bit more mature, and I regret the downsides."

Farewell To A Father by Clint Caward in Good Weekend (1,000 words / 5 minutes). A stunning, moving tribute to Clint Caward's father, who clearly had a hell of a life and made a big impression on his son.Justin Rosenstein had tweaked his laptop's operating system to block Reddit, banned himself from Snapchat, which he compares to heroin, and imposed limits on his use of Facebook. But even that wasn't enough. In August, the 34-year-old tech executive took a more radical step to restrict his use of social media and other addictive technologies. Rosenstein purchased a new iPhone and instructed his assistant to set up a parental-control feature to prevent him from downloading any apps. He was particularly aware of the allure of Facebook "likes", which he describes as "bright dings of pseudo-pleasure" that can be as hollow as they are seductive. And Rosenstein should know: he was the Facebook engineer who created the "like" button in the first place. A decade after he stayed up all night coding a prototype of what was then called an "awesome" button, Rosenstein belongs to a small but growing band of Silicon Valley heretics who complain about the rise of the so-called "attention economy": an internet shaped around the demands of an advertising economy. These refuseniks are rarely founders or chief executives, who have little incentive to deviate from the mantra that their companies are making the world a better place. Instead, they tend to have worked a rung or two down the corporate ladder: designers, engineers and product managers who, like Rosenstein, several years ago put in place the building blocks of a digital world from which they are now trying to disentangle themselves. "It is very common," Rosenstein says, "for humans to develop things with the best of intentions and for them to have unintended, negative consequences."

Space Oddity by Scott Kelly in Good Weekend (3,200 words / 16 minutes). I loved this extract from Scott Kelly's book, Endurance: A Year in Space, A Lifetime of Discovery, which focuses on the excruciating pain of returning to Earth after his body had become accustomed to zero gravity.I bought a Father's Day card for my dad showing a rooster in sunglasses and loud swimming shorts standing in the surf, the summer ocean stretching out behind him. As my dad, Jim, had mesothelioma from working with asbestos and would not be around for another Father's Day, I wanted to write something on the card beyond the platitudes that felt more and more like ticking an empty box. But how do you say thank you to someone who gave so much of themselves to your life, without making it sound like a summing up, as if you're waving goodbye to them as they sail towards the edge of some great abyss? It always seems a shame at funerals when the star of the event doesn't get to hear any of the nice eulogising. Don't we come to know ourselves through what others reflect back? How do we know anything we did meant anything to anyone, unless they tell us, or at least try to? He was a very unique individual, my father. I picked the card with the larking rooster in loud clothes because my dad was a court-jester. He put on magic shows. Had antiquarian card trick books hidden in his wardrobe. Fake limbs where he could hide scarves and handkerchiefs. He could produce a $5 note from a mandarin and a royal flush from his armpit. He filmed my sister's tantrums with David Attenborough narration. He wore a Mexican sombrero to the chicken shop, only satisfied when someone yelled abuse at him from a car. He was the guy in the Woolworths car park with the pony tail and gold Elvis Presley sunglasses, complaining to the security guard with a straight face about how a woman mistook him for Steven Seagal.

Nothing Real Can Be Threatened by Penelope X in The Saturday Paper (2,300 words / 12 minutes). A pseudonymous child sexual abuse survivor describes the process of testifying to the Royal Commission, and then deciding to pursue civil compensation from the Catholic Church for failing to protect her. Utterly appalling, but essential reading.I'm sitting at the head of my dining room table at home in Houston, Texas, finishing dinner with my family: my longtime girlfriend Amiko, my twin brother Mark, his wife, former US congresswoman Gabby Giffords, his daughter Claudia, our father Richie and my daughters Samantha and Charlotte. It's a simple thing, sit ting at a table and eating a meal with those you love, and many people do it every day without giving it much thought. For me, it's something I've been dreaming of for almost a year. I contemplated what it would be like to eat this meal so many times. Now that I'm finally here, it doesn't seem entirely real. The faces of the people I love that I haven't seen for so long, the chatter of many people talking together, the clink of silverware, the swish of wine in a glass – these are all unfamiliar. Even the sensation of gravity holding me in my chair feels strange, and every time I put a glass or fork down on the table there's a part of my mind that is looking for a dot of Velcro or a strip of duct tape to hold it in place. It's March 2016, and I've been back on Earth, after a year in space, for precisely 48 hours. I push back from the table and struggle to stand up, feeling like a very old man getting out of a recliner. "Stick a fork in me, I'm done," I announce. Everyone laughs and encourages me to get some rest. I start the journey to my bedroom: about 20 steps from the chair to the bed. On the third step, the floor seems to lurch under me, and I stumble into a planter. Of course, it isn't the floor – it's my vestibular system trying to read just to Earth's gravity. I'm getting used to walking again.

Heart Of Gold by Will Swanton in The Weekend Australian Magazine (3,300 words / 16 minutes). I loved this profile of an athlete I'd never heard of – in a sport I don't care about – and I think you will, too. That's the mark of a truly talented writer.Four years ago, after learning about the establishment of the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, I believed I was brave enough and ready to confront the sexual and psychological abuses committed against me by a male teacher at my Catholic school. I believed the experience would help release the demons of self-blame, loathing and shame that the teacher had hardwired into my mind, and that throughout life had clung to my very being. Yesterday, weary and traumatised, I faced the last leg of what was an almost unendurable journey, involving a number of unexpected consequential processes. After the royal commission, Victoria Police launched an investigation into the perpetrator of the abuse. After nine exhausting and distressing months, the case was dropped for technical reasons. I learnt that the perpetrator was still teaching and asked the Victorian Education Department that my abuser be removed from classrooms. This attempt failed. As a final attempt at justice, I decided to pursue civil compensation from the Catholic Church, the institution responsible for protecting me from the sexual abuse. The avenue for this process was the Towards Healing protocol. Towards Healing was devised by the church 20 years ago, as a method for assessing sexual abuse compensation claims. The words "towards healing" suggest a gentle process, implying support and the promise of an apology. In due course I discovered the opposite was true.

Crouching Tiger Hidden Dusty by Greg Baum in Good Weekend (4,100 words / 20 minutes). Similar to Will Swanton's story above, I had basically no knowledge of Dustin Martin before reading Greg Baum's cover story on him, but I really enjoyed this read. It's also a classic write-around, where the subject declines to participate, but the writer presses on and comes up with the goods.Shannon Eckstein dives into the lane he shared with Dean Mercer a fortnight ago. It's 5.30am. He expects to be swimming until seven. The morning is clear and crisp. The water in the Olympic-sized pool is warm, 27 degrees. Steam drifts skywards to form the sort of mist you'd expect of somewhere more mystical, maybe a hot spring. To the east, the sun is coming up. To the west, the moon is going down. A small building has a sign on the roof: Miami Swimming Club. Backpacks, tracksuits, thongs, towels and T-shirts are strewn about. All the colours of the rainbow. Eckstein's coach, Alex Beaver, is in a hooded jacket and tracksuit pants. He's cold. He's clutching a coffee. He says the sun and the moon spend a little time together before they go their separate ways for the day. "They're saying good morning to each other. How beautiful is that?" he grins, without waiting for a reply. Eckstein swims until seven. On the dot. He rips off his cap and exhales. Phwoar. Five-and-half hours later, he'll be wearing something altogether more formal. The Australian lifesaving community is about to bury a mate.

++As Dustin Martin walks out of Richmond Football Club and onto Melbourne's Punt Road, his eyes fix on a point in the middle distance and stay there. If they were to stray in any other direction, he would see what he must intuit – that all other eyes are trained on him. It's the same wherever he goes, which must be an overwhelming sensation. In the rigidly blinkered bearing he adopts in public to deal with it, he reminds me of American golfer Tiger Woods at his peak. The eyes may be the windows to the soul, but only those in Martin's most intimate circle get a peep in. In the vernacular of a game and a city, Martin is now simply Dusty. Last Monday, he polled a record number of votes to win the Brownlow medal as the best player in the Australian Football League this season. On Saturday, he will be the central figure as Richmond, a huge and once powerful club, but chronically unfulfilled, plays in its first grand final since 1982. It's long been the club of eternal false dawns and regular Messiahs, of which Dusty is the latest and most exotic. Now 26, Dusty has become a cult figure and the most compelling character in the game. He is sumptuously tattooed and sports a permanent mohawk. He's a high school drop-out from a broken home, whose father Shane Martin is a former bikie gang member now living – under protest – in his native New Zealand, his hopes of returning to Australia all but snuffed out by Immigration Minister Peter Dutton. Dusty's own set of friends and acquaintances might most kindly be described as "raffish". The sum of all this gives him a pseudo-underworld glamour that fascinates many. And he can play football like few others.

Thanks for reading. If you have feedback on Dispatches, I'd love to hear from you: just reply to this email. Please feel free to share this far and wide with fellow journalism, music, podcast and book lovers.

Andrew

--

E: andrew.mcmillen@gmail.com

W: http://andrewmcmillen.com/

T: @Andrew_McMillen

If you're reading this as a non-subscriber and you'd like to receive Dispatches in your inbox each week, sign up here. To view the archive of past Dispatches dating back to March 2014, head here.