Evolution and Bipedalism

The evolution of a species is an account of its adaptation to the demands of its environment/habitat. This process is perfectly epitomized by the almost self-explanatory Darwinian-phrase, "survival of the fittest". The latter explains that a species can only survive and overcome environmental threats insofar as it is successful at adapting to them. This process underlines a species’ instinctual drive to survive. The evolution of hominids necessitated a move, down from all-fours (quadrupeds) to walking upright (bipedalism).

Homo Erectus was the first hominid to undergo this adjustment in response to its environment (Petraglia, M.D). The transition to bipedalism inevitably affected the skeletal structure of Homo Erectus and required and anatomical shift.

Change in skeletal structure

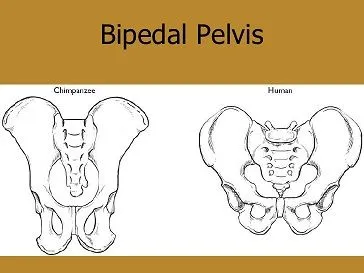

- Pelvis: An elongated and flared pelvis changed to being bowl shaped. The biped pelvis became wider and shortened, like a bowl, to support organs and stabilize body-weight.

slideshare.net/smullen57/3-human-evolution ; Mullen, B._

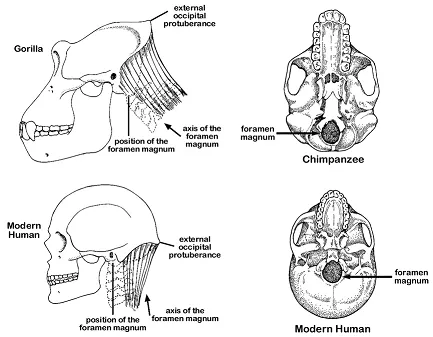

- Skull: A change in the skull to accommodate the change in the spine. In quadruped animals the Foramen Magnum (FM: hole at the base of the skull where spinal-cord connects to brain) trends backwards. For homo erectus to be able to walk upright the FM needed to trend downwards so it could connect and be supported by the spine.

img822.imageshack.us/img822/7767/skullofhumanandgorillam.png

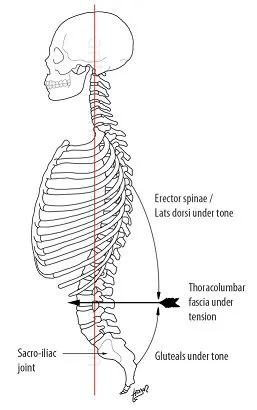

- Spine: Two spinal curves (thoracic and lumbar curves).

http://anthroanatomica.blogspot.co.za/2013/06/; Rogan, T.

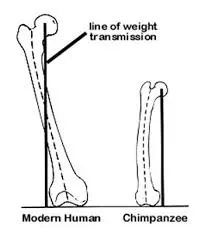

- Femurs: Inward tending femurs.

http://historum.com/blogs/ghostexorcist/1452-how-tell-if-fossil-hominid-bipedal.html

- Chest and torso: A barrel-shaped chest.

(Haviland, Walrath, Prins & McBride; n.d)

The change in skeletal structure was profound. Not only did it lead to the success of the species but also carried a number of repercussions. The change in the pelvic structure led to mothers birthing physically-underdeveloped offspring. A now smaller birth canal could only support small offspring. Subsequently, infants became dependent on intensive and prolonged maternal-care after birth.

Pregnancy and delivering offspring became challenging, even dangerous. The number of birth-related deaths rose with the change in pelvic structure. Mothers had to expend more energy on their underdeveloped children, carry them around and provide more than before.

Despite the challenges it created, bipedalism inevitably led to the success of Homo Erectus. Bipedalism saved locomotive energy which meant less energy output when in motion. This resulted in Homo Erectus having a lower caloric expenditure than before.

Homo had more time to socialize, move over greater distances, tend to each other and investigate their environment(s).

Bipedalism increased their line of sight and provided an advantageous perspective over their habitat. Homo Erectus would have been able to peer across and observe the grassland-habitats they inhabited. This allowed them to proactively spot danger and discover resources.

Most importantly it can be argued that bipedalism demanded a higher brain capacity. This boost in brain-power would have helped in simplifying once challenging tasks and obstacles. The latter would have inadvertently changed the species’ collective paradigm (however primitive it might have been) to not only survive but flourish and thrive.

One of the most important factors bipedalism had was that Homo Erectus had freed up its hands. This lead to increased and more successful foraging, intricate social interaction like touching and communicating and social-grooming. This also allowed Homo Erectus to create tools which not only simplified their existence, but enabled them to protect it. (Strickberger, M.W. p.474).

Bibliography:

Petraglia, M.D, 1988. Early Human Behaviour in Global Context: The Rise and Diversity of the Lower Palaeolithic Record. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

Spencer, H, 1864. The Principles of Biology. 1st ed. London: Williams and Norgate.

Haviland, Walrath, Prins & McBride, [n.d]. Evolution and Prehistory: The Human Challenge. Boston: Cengage Learning:

Strickberger, M.W, 2000. Evolution. 3rd ed. MA: Jones & Bartlett Publishers