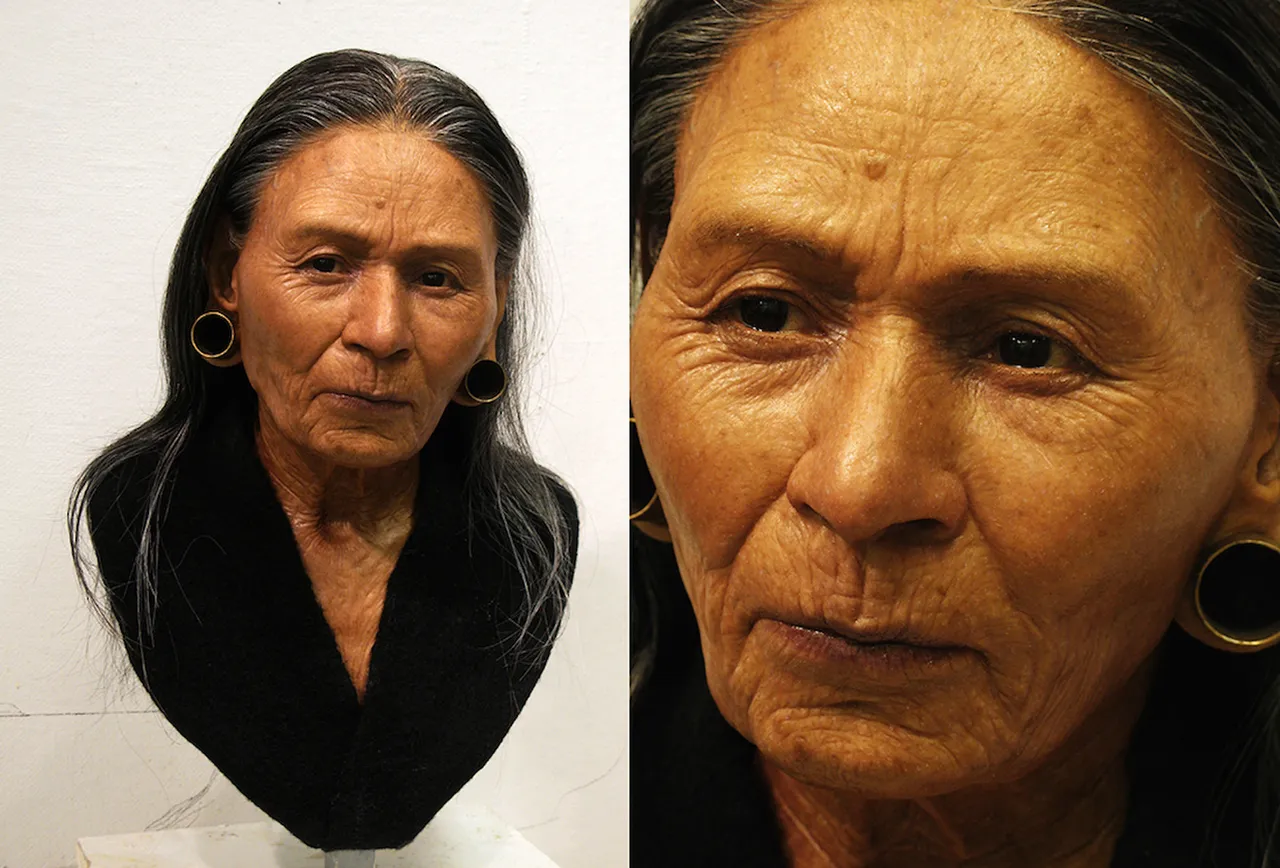

At first glance, the wrinkled face of a dark haired-woman wearing round, gold earrings looks incredibly real. But it's not — it's a reconstruction crafted from modeling clay, based on the skull of a Wari queen who lived about 1,200 years ago in what is now Peru.

Peruvian and Polish archaeologists unearthed the queen in a pyramid mausoleum known as El Castillo de Huarmey (Huarmey's castle), located north of Lima, in 2012. The tomb held the remains of 58 noblewomen, including the queen, who was buried in private chamber, according to National Geographic. All of the women were part of the Wari culture, a people who lived in the region from A.D. 700 to 1000, long before the Inca rose to power.

The queen's tomb held jewelry and other lavish artifacts, including a copper ceremonial ax and a silver goblet. It also held her skull, which archaeologists gave to Oscar Nilsson, a forensic artist based in Sweden, so he could reconstruct her features for the world to see. [Photos: The Amazing Mummies of Peru and Egypt]

Advertisement

The skull was far too valuable to work on, so Nilsson used a computed tomography (CT) scanner to make a virtual, 3D image of the skull. He then sent the digital data to a 3D printer, which made a replica of the skull in vinyl plastic.

That's when the challenging work began. To forensically re-create a face, it's important to know the person's sex, age, weight and ethnicity — factors that influence the thickness of facial tissue, Nilsson said.

Nilsson knew the Huarmey Queen was at least 60 years old. Armed with that knowledge and more, he got to work putting 30 plastic pegs of a certain length all over the queen's replica skull. "After this, it was time to start up the fun; begin sculpting the face!" Nilsson wrote in an email to Live Science. "This was made from the 'inside out,' muscle by muscle."

He used plasticine clay to sculpt the muscles, relying on methods that help forensic artists reliably rebuild a person's eyes, nose and mouth. "The ears are more speculative," he said.

Next, he covered the muscles with a layer of skin. "Details, wrinkles and pores are sculpted to get it [to be] realistic," he said. "When I'm finished sculpting the face, I make a mold, in which I then cast the face in silicone. In this way, I can get it very realistic. It looks almost like a real person, even to me."

Nilsson used prosthetic eyes in the reconstruction, as well as real human hair that he inserted, strand by strand, into the silicon scalp. "We actually used Peruvian human hair, bought in Peru by the Polish archeological team," he noted.

He even gave the royal woman metal earrings with a golden and worn patina. "They are an exact replica of her actual earrings, found in her tomb," he said.

In all, Nilsson spent 220 hours on the queen's reconstruction, which he finished in late November. He described the restoration as "an elder woman's face with a lot dignity about it. She looks wise [and] experienced, as well as a bit tired and maybe sad, or thoughtful," he said. "She is thinking of something, maybe a memory way back, as older people do sometimes."

The technique Nilsson used to re-create the ancient queen's likeness is also used by law-enforcement agencies when a victim cannot be identified. About 70 percent of these cases are solved once a reconstruction is made, he said. "It is not a portrait of the deceased, but you get a good image of what the face looked like."

The Wari queen's reconstruction is now on display in a new Peruvian exhibit at the National Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw, Poland.

Original article on Live Science.