Many useful substances discovered by humans throughout history have proven a poisoned chalice - we've already looked at one such material, asbestos.

Another handy metal whose practicality belies its danger is lead.

Much like asbestos, lead was a silent assassin ubiquitous in civilised societies for millennia. Only in the last half-century have law-makers wised up to the threat of lead, which has subsequently fallen by the industrial wayside.

Promising Properties

Lead is a lustrous metal easily extracted, in small quantities, from raw ores such as cerussite. So numerous are its useful properties that, were it not incredibly toxic, it would remain a cornerstone of modern industry.

Malleability, resistance to corrosion, high density and insolubility made it an ideal candidate for water pipes, container linings and decorative paints.

The Romans put lead to use in plumbing systems, murals and even lead acetate wine sweetener.

However, prolonged exposure through contaminated beverages and dust is thought to have had a devastating effect on the longest-serving members of Roman society, particularly the ruling class. Their long-term exploits with the metal had a part to play, according to many historians, for their civilisation's downfall; the documented prominence of dementia and mental illness among the Roman aristocracy has since been attributed, at least in part, to their misinformed and self-destructive everyday use of lead.

The Roman empire was not the only culture to fall foul of lead's allure.

16th and 17th century European aristocrats used powdered lead to obtain the sought-after 'white-faced' look of the time, and the powder was credited for Queen Elizabeth I's 'youthful' appearance.

Unfortunately, a common side effect of lead poisoning is tooth decay, and, unsurprisingly, dental problems among the profligate European higher-ups were common.

Ironically, the dental replacements were often made of - you've guessed it - lead.

Lead Poisoning

Although lead toxicity as a result of one-time exposure to the metal is rare, repeated long-term contact results in chronic lead poisoning.

Lead absorbed into the blood stream displaces vital metals ions such as iron, calcium and zinc. This has many repercussions, including limiting the blood's ability to transport oxygen and promoting a buildup of lead deposits in organs (particularly in bones and teeth).

Particles of lead also bind and block neurotransmitters such as the glutamate receptor, impairing brain function and limiting development.

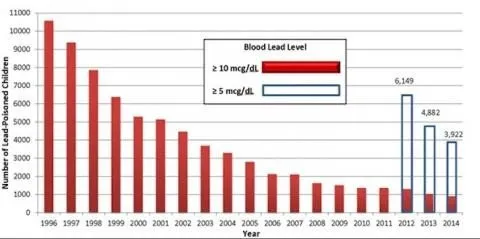

While lead exposure can have a profound impact on adults (as the Romans and Renaissance Europeans discovered) the detrimental effects of lead poisoning are particularly problematic in the young, whose brains are not yet fully developed; repeated exposure to lead can result in developmental and emotional impairments in children, along with abdominal pain, anemia (haemoglobin deficiency) and loss of fine motor skills.

Industrial Longevity

Despite the documented risks of everyday lead exposure, even modern-day western society has struggled to resist temptation. Post-Industrialist society has not been above ill-advised applications of lead; the use of lead in commercial paints - which proved dangerous to children after a sugar fix - wasn't outlawed in the United States until 1978, and other commercial uses were widespread even into the early 21st century.

For instance, leaded petrols were employed to tackle the problem of knocking in internal combustion engines, primarily car and motor vehicle engines.

The traditional combustion engine works best if all of the compressed fuel ignites as the spark plug fires. However, volatile fuels have the tendency to combust spontaneously under pressure, so the compression stroke of the engine has the tendency to trigger premature combustion.

This phenomenon damages the engine's pistons and chamber, causing an audible 'knocking' sound in the process.

The addition of lead to a petroleum mixture raises its temperature of combustion, lowering the chance of premature combustion and thus mitigating against the risk of knocking and engine damage.

However, the combustion of leaded petrol releases lead particles, along with other residues, as exhaust fumes.

The build-up of atmospheric lead concentration over decades has been identified as a leading cause of chronic lead poisoning in recent years.

The turn of the century marked the end of the lead era, with unleaded petrols replacing their polluting counterparts and a plethora of new technologies and materials developed as alternatives to incumbent lead-based equivalents.

Out Of Fashion But Not Obsolete

While lead has been eradicated from most materials that could conceivably find its way into the human body, there are some situations in which lead is so useful that its risk is tolerated.

For example, X-ray operators in hospitals are protected from harmful ionising radiation by lead lined aprons and screens. While dangerous lead exposure is a possibility for long-serving medical staff, these (mitigated) risks are far outweighed by the potential dangers of heavy radiation doses.

Despite the commercial shift away from lead to satisfy environmental compliance regulations, the metal still dominates certain industries; lead-acid batteries represent a large sector of the energy cell industry (88% of the US battery industry in the mid 2000's).

If you enjoyed this article and would like more, follow the everyday science blog for your daily dose of science.

References:

Wisconsin Department of Health Services

www.healthline.com

Hank Green's Sci Show

www.wikipedia.org

Royal Society of Chemistry

www.naahq.org