Textures that oppose water are fundamental for everything from rainwear to military tents, yet traditional water-repellent coatings have been appeared to continue in the earth and amass in our bodies, as are probably going to be eliminated for wellbeing reasons. That leaves a major hole to be filled if analysts can discover safe substitutes.

Presently, a group at MIT has thought of a promising arrangement: a covering that not just adds water-repellency to common textures, for example, cotton and silk, but at the same time is more compelling than the current coatings. The new discoveries are depicted in the diary Advanced Functional Materials, in a paper by MIT educators Kripa Varanasi and Karen Gleason, previous MIT postdoc Dan Soto, and two others.

"The test has been driven by the natural controllers" on account of the phaseout of the current waterproofing synthetic concoctions, Varanasi clarifies. Be that as it may, it turns out his group's option really beats the regular materials.

"Most textures that say 'water-repellent' are really water-safe," says Varanasi, who is a partner educator of mechanical building. "In case you're emerging in the rain, in the long run water will get past." Ultimately, "the objective is to be repellent - to have the drops simply skip back." The new covering comes nearer to that objective, he says.

Due to the way they gather in the earth and in body tissue, the EPA is updating directions on the long-chain polymers that have been the business standard for a considerable length of time. "They're all around, and they don't debase effortlessly," Varanasi says.

The coatings presently used to influence textures to water repellent for the most part comprise of long polymers with perfluorinated side-chains. The inconvenience is, shorter-chain polymers that have been considered don't have as quite a bit of a water-repulsing (or hydrophobic) impact as the more extended chain variants. Another issue with existing coatings is that they are fluid based, so the texture must be submerged in the fluid and afterward dried out. This tends to stop up every one of the pores in the texture, Varanasi says, so the textures never again can inhale as they generally would. That requires a second assembling venture in which air is blown through the texture to revive those pores, adding to the assembling expense and fixing a portion of the water security.

Research has demonstrated that polymers with less than eight perfluorinated carbon bunches don't continue and bioaccumulate so much as those with at least eight - the ones most being used. What this MIT group did, Varanasi clarifies, is to consolidate two things: a shorter-chain polymer that, independent from anyone else, gives some hydrophobic properties and has been upgraded with some additional concoction preparing; and an alternate covering process, called started compound vapor testimony (iCVD), which was produced lately by co-creator Karen Gleason and her associates. Gleason is the Alexander and I. Michael Kasser Professor of Chemical Engineering and partner executive at MIT. Acknowledge for coming up for the best short-chain polymer and making it conceivable to store the polymer with iCVD, Varanasi says, goes essentially to Soto, who is the paper's lead creator.

Utilizing the iCVD covering process, which does not include any fluids and should be possible at low temperature, delivers a thin, uniform covering that takes after the shapes of the strands and does not prompt any stopping up of the pores, along these lines killing the requirement for the second handling stage to revive the pores. At that point, an extra advance, a sort of sandblasting of the surface, can be added as a discretionary procedure to build the water repellency significantly more. "The greatest test was finding the sweet spot where execution, solidness, and iCVD similarity could cooperate and convey the best execution," says Soto.

The procedure chips away at a wide range of sorts of textures, Varanasi says, including cotton, nylon, and cloth, and even on nonfabric materials, for example, paper, opening up an assortment of potential applications. The framework has been tried on various sorts of texture, and in addition on various weave examples of those textures. "Numerous textures can profit by this innovation," he says. "There's a great deal of potential here."

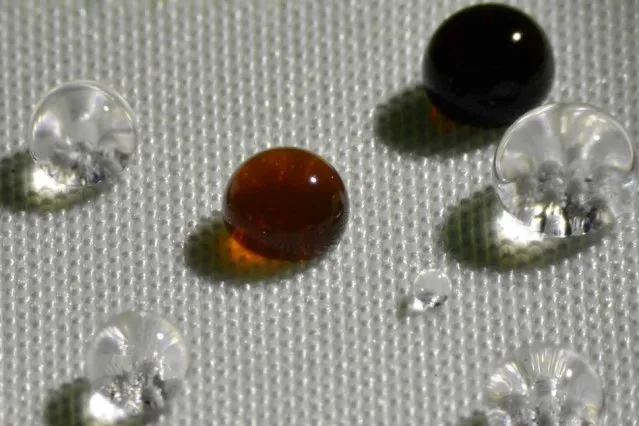

The covered textures have been subjected to a blast of tests in the lab, including a standard rain test utilized by industry. The materials have been assaulted with water as well as with different fluids including espresso, ketchup, sodium hydroxide, and different acids and bases - and have repulsed every one of them well.

The covered materials have been subjected to rehashed washings with no corruption of the coatings, and furthermore have finished extreme scraped spot tests, with no harm to the coatings after 10,000 redundancies. In the end, under extreme scraped area, "the fiber will be harmed, yet the covering won't," he says.

The group, which additionally incorporates previous postdoc Asli Ugur and Taylor Farnham '14, SM '16, plans to keep chipping away at upgrading the synthetic equation for the most ideal water-repellency, and would like to permit the patent-pending innovation to existing texture and garments organizations. The work was bolstered by MIT's Deshpande Center for Technological Innovation.

Guys,if you like my post please upvote and comment on my post, that will really motivate me to write more.