As seen above, this is an Igbo proverb from South-Eastern Nigeria that tells us how the great can be reduced to a pathetic state by tragic circumstance -- especially if the tragic circumstance is losing their source of greatness. The short story is derived from many such tales in Igbo folklore. Thanks in advance for reading and I hope you enjoy it.

THE HUNTER

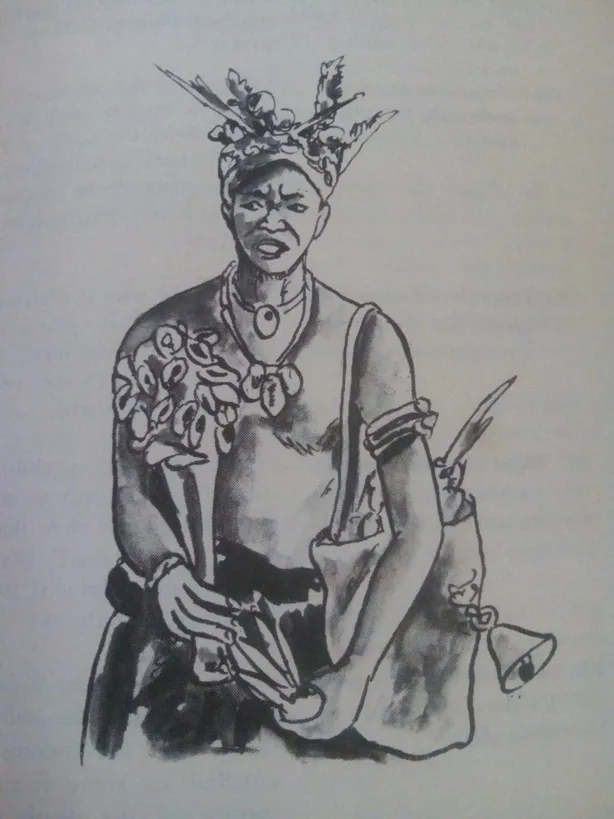

Once there was a hunter in a faraway village in the East. His name was Akuegube. He was not just a hunter but a great hunter of great skill and greater fame. No animal could escape his trap, however small or big and none could outrun his arrows, however fleet of foot. An unmarried man, he lived on the edge of the village so as to have easy access to the forest where he plied his skillful trade. He had an elder brother who was a farmer married to a lovely wife named Mgborie and they had two children.

However, even for great men, there is sometimes a great downfall that lies in wait. Little did Akuegube know that his own was imminent.

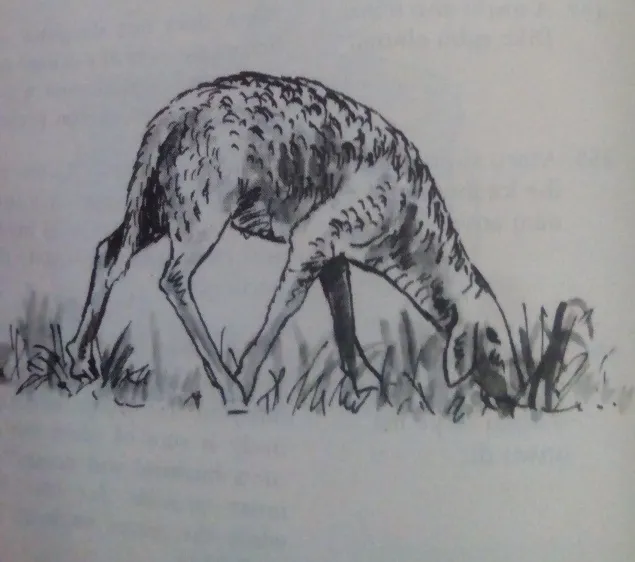

On that fateful day, he went hunting as he normally did long before the sun was up in the forests as familiar to him as the back of own hand. It had rained the night before but this was no impediment to a hunter of his skill and experience. Soon he had picked up a promising trail and after He had tracked a particularly big antelope to a dense part of the forest. The sightlines were unclear from the ground so he climbed a tall tree in order to shoot it from that superior vantage.

He had it in his sight. He took his bow with both hands and balanced with his feet on a strong branch. Unfortunately, the moisture from the night's rain was enough to make his footing slip at the moment of firing and, in that tragic moment, he fell from the tree, plunging through many branches that slapped at every inch of his body as he fell including his face.

He landed in a big pile of leaves and soft grass, with a big but muffled thud. After getting his bearings, he struggled to his hands and knees, shaken but otherwise unharmed by such a high fall. A small mercy, it turned out, when he felt drops of hot liquid fall from his eyes to the backs of his hands but saw them not. He saw not the drops nor did he see his hands, not the leaves and stalks and grass his fingers clutched and pressed, not his knees grinding into the soil. He felt a great heat in his eyes and heat ran down his cheeks but he saw nothing.

His farmer brother, concerned at his absence, sought him in the forest and thankfully heard his calls for aid. They found each other and he brought Akuegube home -- a home he would enter but never see again.

Weeks passed. Months passed. His wounds healed, his eyes did not. It fell upon his elder brother to care for him but in their land, there is a saying: nwata a kwo n'azu amaghi na ije e teka which means that a child carried on someone's back knows not the length and difficulty of the journey. Even as he grew accustomed to some measure of comfort in the scarred darkness, his brother died suddenly, leaving his family and Akuegube in dire straits.

The wife, as many women with children are wont to do, wept for many days, mourned heartbroken then sobered and got on with the business of survival. She took up some small farming, selling her crops in the market and she took to grinding utaba or snuff, a powder taken through the nostrils by men.

Akuegube on the other hand was at loose ends. Without the comparative comfort of his brother's backing, he was left in difficulty. His blindness made it almost impossible to do any legitimate work and begging was of course unacceptable.

And so it was one dark day that Akuegube turned his mind to ... other options.

Soon, the villagers began to complain of missing money, missing chickens, missing yams and other sundries. Soon it came to the attention of the elders who called all the people of the village together in the village square. The elders reminded them of who they were, of the nobility of their culture, of how theft was corrosive to the community. All were greatly moved and all returned to their homes.

For a while, the thefts stopped. Weeks passed again. The time, however, came again that Akuegube felt the need to act. Once again, he ventured out in the dead of night, his blindness of no disadvantage at that time, and once again, he stole the chickens and cocoyams of his fellows.

They say that we should be careful what we do because we become what we can eventually become our actions. Akuegube, by getting into the habit of stealing, found he had developed the heart and mind of a thief - furtive, suspicious and greedy.

Meanwhile, Mgborie, the wife of Akuegube's brother, was managing her life as best she could, keeping herself and her children fed and, as much as possible, Akugube himself also. She was accomplishing this by farming and by her new-found utaba business, one she proved to have some talent for; her utaba was of the finest quality.

There was a problem though; every week, she would put out her fine utaba on the windowsill near the back of her house before going to the market and the farm. Whenever she came back, she would find it much reduced. Someone was stealing her utaba. She had reported to the council of elders and they invited her and Akuegube, her closest adult relative and neighbour, as culture demanded.

The council asked Akuegube if he had any hand in this matter. He responded that one does not steal meat from his own pot. He then began to lament: "Akuegube! Akuegube! You all know who I used to be! Is it because I am blind that my name will now be in the marketplace? Akuegube! Akuegube!"

Mgborie returned to her home and Akuegube to his, both unsatisfied for different reasons - she because the thief was still a mystery and Akuegube with the resentful annoyance of one not-so-unfairly accused.

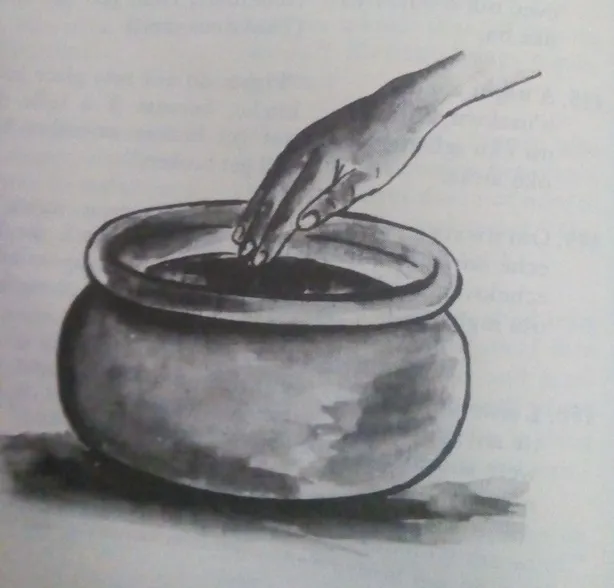

In Mgborie's case, she was now determined to find a final solution to this snuff-stealing "ghost". To her mind, the snake that does not prove itself a snake will be used as a rope. Therefore, she devised a plan. First, she bought some fine red pepper, roasted it to blackness, pounded it to powder and dried the life from it in the blaze of the noonday sun. While this transpired, she made her next batch of utaba.

When all was in readiness, she fulfilled the next stage of her plan. She took the thoroughly dried pepper and mixed it into the utaba with such finesse that even an eagle with its powerful eyes would never know the difference. She then placed the container of now-sabotaged utaba on the same window-sill just as she always did and went to the market as she always did.

Soon, our bold thief knocked at the door as usual and, as hoped, no answer came. The thief made their way to the usual place and as expected, found his quarry waiting in the usual windowsill. The thief took a large measure of utaba and filled his own container as he usually filled and left as he usually left. In the comfort of his own lonely house, the thief relaxed, really got comfortable in his favorite chair and took a great, even excessive measure of delicious utaba into his right nostril.

Suddenly, on the outskirts of the village, a great screaming broke the silence of the hot afternoon. Villagers came running to find out what was the problem and they found Akuegube, flailing, tears running from blind eyes, hand over his face, blood running between the fingers, shrieking louder than any animal he had ever killed. It took them some time to realize he was calling a name:

"Mgborie OOOOOOOO!!!!! Mgborie has killed me oooooooo!!!!! Ewooooooo!!!!!!!!"

So some of the villagers did the obvious and went to call Mgborie where she had stopped to chat with a friend on her way back from the market. They said her brother-in-law was accusing her of killing him, that she should come and speak for herself.

So Mgborie came to the edge of the village to see her accuser. The crowd parted before her and she arrived at the center, in front of Akuegube's house. When she saw what had become of her blind brother-in-law, all present were quite shocked when she burst into great laughter. She laughed so hard that she in fact fell on the ground with her legs in the air; great undignified peals of amusement with tears running from her eyes. It was a strange mirroring; both her and her brother-in-law rolling on the ground with liquid flowing down their cheeks and loudly performing -- although for very different reasons.

When she finally calmed down, she announced that Akuegube was the thief of her utaba. When the shocked villagers turned to him, the blind brother in his distraught state, admitted to far more thefts than just the utaba. When they asked Mgborie how come he was in this state, she described the devious trap she had laid for the thief and that clearly, in vengeful relish, he must have taken a much bigger dose than necessary. Hence his current suffering.

After a few cups of water had been splashed in his face to (slightly) reduce his agony, Akuegube was brought before the council of elders once more with a very different outcome.

As we say, mkpuru onye kuru, ka o ga horo. What one sows is what they reap.

all illustrations by Olu Byron

Glossary

Utaba: snuff, made from something not entirely unlike tobacco, taken through the nostrils for intoxicant and social enjoyment

Ewoooooooo: Actually, "ewo", a scream of woe and pain

Oooooooo: a wordless expression of discomfort and pain

Thanks for reading, I hope you liked it!