Before I say anything, to avoid any doubt, doping is cheating, and cheating is bad.

When an athlete I like is caught doping, it's hugely disappointing and makes me question what it was I saw, what I enjoyed. What at must be like to be a teammate of someone caught doping, or a member of the backroom staff, when the actions of someone you've put trust in mean you either lose something you thought you already had, or leave a giant hole in your team for the forseeable future. The consequences of working with a cheat are wide reaching, and in any team sport the idea of letting down the rest of your team should horrify any athlete.

BUT, it's more complicated than that

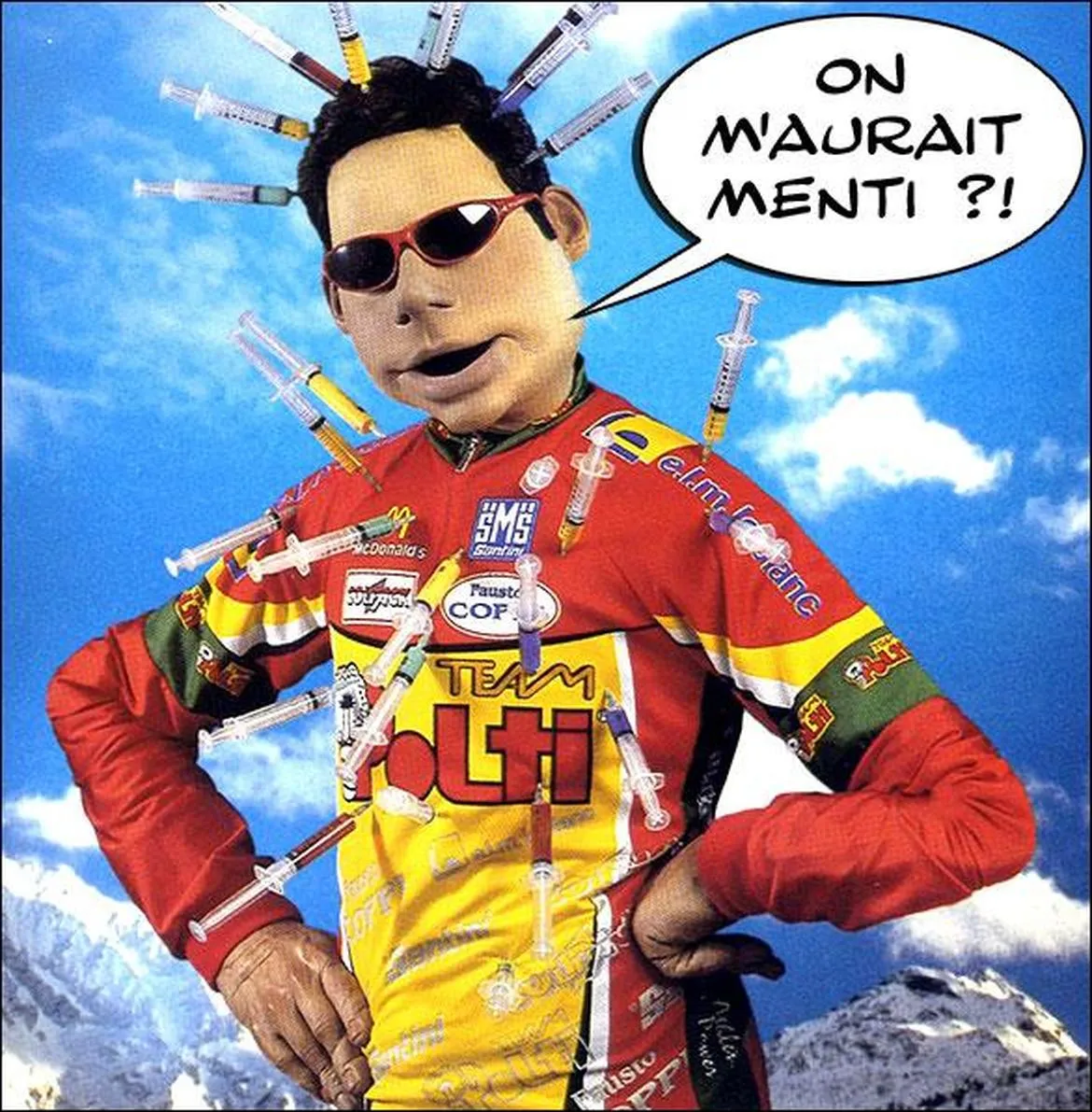

The culture around doping in English speaking countries is not a universal thing. French writer Francois Thomazeau, when talking about Bradley Wiggins' use of a theraputic use exemption on The Cycling Podcast, referred to how in France doping is not a moral issue, but a legal one. Whereas in Britain, the idea an athlete might use a drug with the potential to enhance their performance is enough to ruin a glowing reputation, in France would be seen as someone just acting within the rules. Also in France, Richard Virenque, who's drug taking was so notorious he's parodied on national television with needles hanging out of his head (below, as he appeared on Canal+ show Les Guignols de l'Info), is still regularly invited as a guest of honour to the Tour de France. This is not to say the French don't take doping seriously, it's a criminal offence, but they don't treat it as the most morally abhorent thing someone could ever do.

In Britain, Ireland and Australia, at least in the mainstream press, anyone caught doping almost instantly becomes persona non grata. When Justin Gatlin won the 100m World Championships in London last year, he was booed every time he took to the track, people questioned why he was allowed to race, treated him with the assumption he was cheating at that moment. The attitude was almost that even though he was allowed within the rules of the sport to compete there, that he shouldn't. That's where I have a problem. After someone has served their punishment, they should be treated fairly.

Punishments

The entire purpose of any set of laws, regulations, or even informal rules, is to discourage undesirable behaviour. Undesireable behaviour doesn't have to be immoral behaviour, it can even be for the perpetrator's safety. While crimes like fraud and assault and rape are typically considered immoral, not many people would suggest not having a red rear reflector on a bicycle after sunset is a moral decision. Stupid maybe, but not immoral. To protect victims of indiscretions, rules are in place that if violated, result in a punishment. That punishment serves to prevent the rule violation in the first place, to protect potential future victims from also suffering, and with the intention of rehabilitating the perpetrator so it doesn't happen again. When a violent criminal is given a prison sentence, the purpose is to keep them away from the general public for long enough that they can reflect on what they have done and hopefully by the end of it they won't feel compelled to re-offend. One of the key elements in a just justice system though, is that the punishment fits the crime. If someone didn't have a rear reflector on their bicycle, it wouldn't be just to throw them in prison for it, whereas a small fine may be seen as acceptable.

In sport, this system of justice still applies. On a rugby field, if you collapse a scrum, a dangerous thing for all involved, the other team is awarded a penalty, which is a potent gift which may lead to points or territory. The purpose of this is to discourage the dangerous act from happening. If it keeps happening, the player responsible is sent to the sin bin for 10 minutes, which serves to prevent the act from happening for that time. If a player commits a serious, deliberate act of foul play, they will get a red card and a suspension. This is again meant to initially prevent, the player knows they will be punished if they do it so they don't do it, and if it fails to prevent, it protects future victims for the length of the suspension. This is all with the intention that if you punish an act severely enough, players will stop doing it so as to avoid sanction.

How does this apply to doping?

Doping, like all other offences, is subject to a system of punishments. This system of punishments is also intended to be proportional to the violations. Certain substances get bigger bans than others, repeat offences get longer bans than first time ones. In Europe, the concept of proportionality comes up in the Meca-Medina ruling, where the European Court of Justice ruled that if doping rules go beyond what is necessary in order to effectively combat doping, they are deemed to restrain trade. While this doesn't apply worldwide, this is the purpose of sanctions, to combat doping.

It's in terms of proportionality where the mainstream debate sticks with me, and brings us to the events of the last week.

The case of Gerbrant Grobler

Full disclosure, I have no skin in this game. I'm not a Munster fan, I don't know Grobler or any of his friends or family personally. So here it goes.

Gerbrandt Grobler is a 25 year old rugby player from South Africa. In 2013, aged 21, he suffered an ankle injury, and missed all but one game of the 2014 regular season. After a game in October that year, he tested positive for drostanolone, an anabolic streoid. He admitted to it and recieved a two year ban. From the outside, this appears to be a young man, who in missing a whole year of rugby was in a pretty desperate state, making a very bad decision. Young men notoriously make bad life decisions. That doesn't make it ok, it was the wrong thing to do, but I think it's worth keeping in mind this isn't some evil genius trying to trick the world into seeing himself as a hero. He served his two year ban, and when he came back signed for Racing 92 in Paris.

Then, in the Summer of 2017, he signs for Munster, in Ireland, a country where the two most famous sports writers are famous for their work on doping in the Tour de France. This was reported quite widely at the time, though given he signed during the Lions tour and not at a time of year where provincial rugby dominates the sports news cycle, some people may not have noticed. Fast forward to January 2018, and he's fit to play, and it's a Champions Cup week, and suddenly people perk their ears up. "Munster sent a message to their stakeholders that it's ok to juice if you're prepared to face the music if caught red-handed" was the headline in the Independent on Sunday.

The story was somehow that Munster had tarnished their brand by signing a man who was allowed to play. Once a doper, always a doper, signing Grobler means Munster are somehow encouraging young players to dope? One of my finest tweeps (is that still a word?), Munster's premier fansite <threeredkings.com> was fairly combative about the story. They openly questioned why it took six months for the outrage, and why a young man isn't allowed a second chance. This led to a certain prominent writer and former cyclist to tweet this:

I see my friends @threeredkings have changed the Munster Creed. It’s now: ‘Irish by birth, Munster by the grace of steroids.’

Paul Kimmage (@PaulKimmage) January 14, 2018

‘

Small problem, Paul Kimmage has admitted to doping himself. Paul has a lot of strong opinions, and wrote a piece himself about how it makes Munster look bad to hire Grobler. From my perspective, anything regarding repuation is setting a moral standard for what you want from an organisation, not a legal or technical one. It's unlikely that the lasting effect of steroids in Grobler's body make up for the two years he's missed on the rugby field. It's inconceivable to me that, provided he's not doping now (which he, like all pro athletes, is tested for) he's a more capable rugby player than he would be were he not suspended. If the issue is morality, we must excommunicate all dopers, which would include Kimmage. This led me to tweet this:

Paul serious question, does it not reflect poorly on @Independent_ie that they publish the columns of an ex-doper?

Roarz (@Roarzz) January 14, 2018

This isn't about ability, this is about the message it sends out. Obviously I don't think taking amphetamines in the 80s makes him a better writer now, but he did something wrong and what message does that send to the Indo's advertisers?

Did I do this to wind Kimmage up? Maybe. Did I expect a satisfactory answer? Not at all. This is more about exposing the hypocrisy. I've seen a defence of Kimmage that he has taught a lot of people a lot about doping in sport, and that means he's redeemed himself. That's not a terrible idea, and one I might even subscribe to, the problem is that's in hindsight. What if Grobler goes on to do the same? What if, instead of showing Munster academy lads how to dope, he passes on how stupid a thing it is to do? Before it happens, we can't know what the future holds.

Is doping the worst?

In my personal opinion, doping is disproportionally punished.I don't mean in the sense that the bans are too short (Brian O'Driscoll said he woudn't be opposed to life bans at first offence on Newstalk, but that would violate EU law as much as anything). Doping is primarily banned because it's dangerous, and by banning it sporting authorities reduce the risk athletes are required to take in order to succeed.

What Grobler did, is fundamentally less bad than what Calum Clark did to Rob Hawkins elbow, which had a direct victim, was a violent act, and only got a 32 week suspension. In 2009, David Attoub effectively attempted to blind Stephen Ferris. It was also a second similar offence. He got 70 weeks, still less than Grobler. I'd possibly consider a life ban for serious gouging offences it's that serious. Why doping is a more serious form of cheating than eye gouging is hard for me to work out.

Doping is bad, and all efforts to eradicate it are good for sport, but please, it's not the end of the world.