Since October 30th, I have been reading every book of Robert Caro's immense biography of Lyndon Johnson, and it has taken me a month and a half, roughly, to do it, though I did occasionally read other books during it, as a way of giving myself a break. Last week, I finally finished.

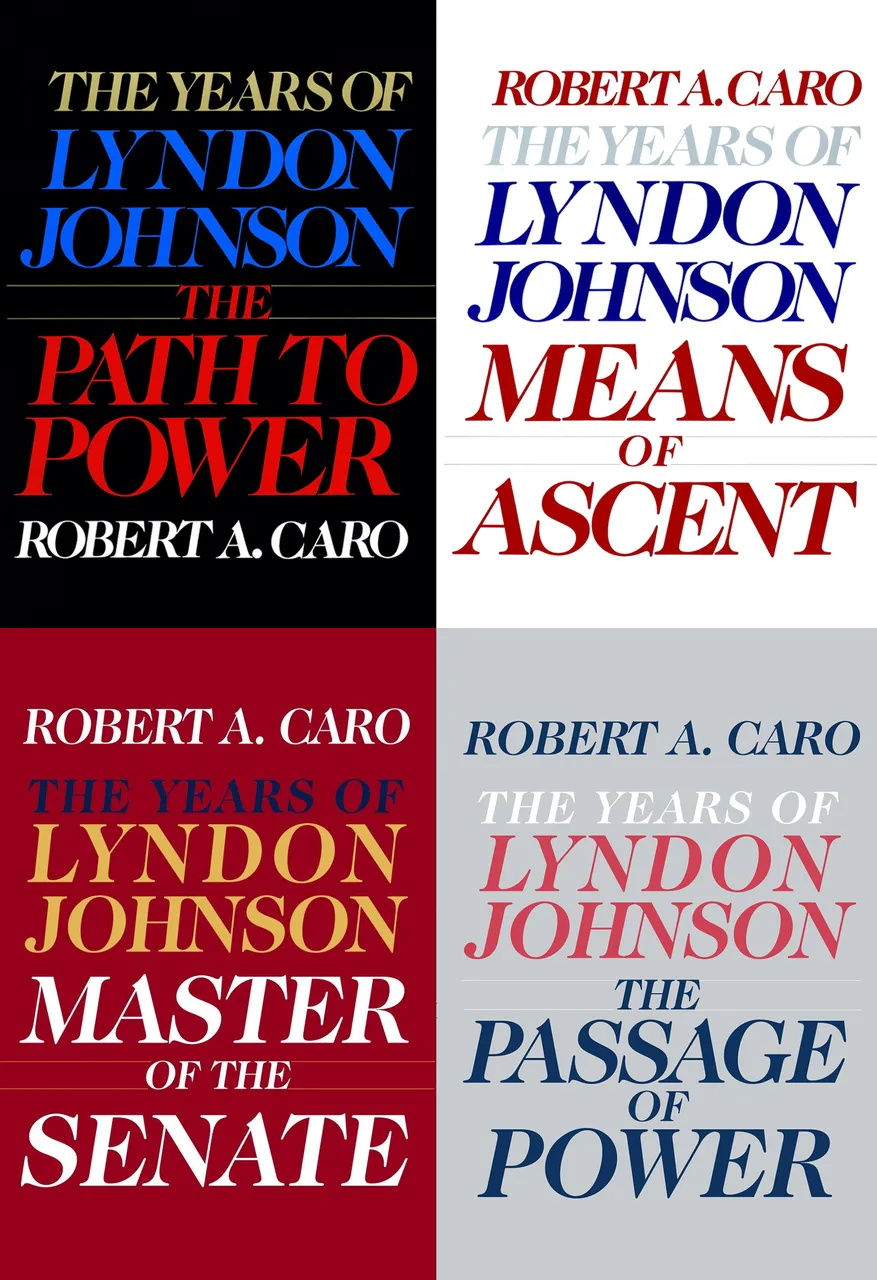

Published by Alfred A. Knopf. The Path to Power, published 1982; Means of Ascent, published 1990; Master of the Senate, published 2002; The Passage of Power, published 2012; the fifth and final volume, dealing with the bulk of Johnson's presidency, and his retirement, is still being written and, according to Caro, years from completion.

A project of over three thousand pages, having occupied over forty years of the author's life - Caro is 83 now, he was not even 50 when he began - of such scope and detail and dedication that a volume comes out at a rate of one every decade. It has been universally, unanimously critically acclaimed and awarded numerous prizes. That it is a monumental achievement is so beyond the obvious that to speak it is to speak that water is wet.

Is there any point to my reviewing it? One hardly needs my recommendation to decide to read it when the recommendations of numerous people far smarter than I exist.

Still, here I am. The only real qualification for me reviewing a book is for me to have read it. So here I am - reviewing four.

I repeat: this is a monumental achievement. Caro has spent over forty years on this and it shows in the incredible, granular level of detail he puts into these books. You are not merely reading of Johnson's life. Caro is immersing you in Johnson's life, in the place Johnson lived - and in the times Johnson lived in. In calling this The Years of Lyndon Johnson, he attempts to capture both the man and his times.

Caro is an incredible writer, but he's not an incredible writer in the way that, say, David McCullough is. McCullough is sharp, highly refined and distilled in his writing. Caro is almost unwieldy. His paragraphs may stretch over half the page, covering numerous commas - and yet it all flows together well. It is articulate, a touch repetitive, verbose, deeply insightful - and smooth, but smooth in a way completely different from most other writers.

This granular thickness and density I adore reading but I warn that if you used to the sharp deftness of David McCullough, whose prose however rich is comparatively sparse to a writer such as Caro, you may find this harder reading, requiring both patience and perseverance.

The result is rewarding, though - Caro is long, often digressing, but immaculate, setting the scene for everything extremely well, delving deep into Lyndon Johnson. By the time you've finished all four volumes, you'll be convinced that, had Nixon not come around, Johnson would've gone down as our most psychologically complex and interesting President.

Caro is often critical of Johnson, perhaps even too much so, but never without reason, and when it comes Johnson's achievements in helping his constituents or in the area of civil rights legislation he is fulsome in his praise. To paraphrase: "It may have been Lincoln who freed the black man from the chains of slavery, but it is Lyndon Johnson who brought him into the voting booth and forever made him part of America's democracy."

The series stands as a testament to research: Caro has conducted over one thousand interviews. He and his wife have delved very deeply into various libraries and archives in order to find as much as they possibly can.

This is not merely a biography of Lyndon Johnson. To say it is a biography of Lyndon Johnson is accurate, but it is also a simplification. This is also about the era and times Lyndon Johnson grew up in and served in. This is a chronicle of the acquisition and usage of power, power specifically in the realm of influence by way of government and by way of cash.

As such, Caro explores the reasons that Johnson sought power with such fervor. He explores the methods through which Johnson obtained that power and the ways in which Johnson used it. It becomes very clear that Johnson has a knack for finding, or even creating wholesale, power in whichever position he finds himself. (With the sole exception of the Vice-Presidency.)

So too does Caro explore the times. His description of the Texas Hill Country, and of Johnson's ancestors the Buntons and the Johnsons, in the first volume, really sets the scene and his descriptions of the Hill Country, both in Path and Means, do a great deal to illustrate the abject poverty that the residents of the Hill Country lived in, a poverty that is literally incomprehensible today.

As much as the books present Johnson's many and disturbing character flaws, they also highlight when Johnson does good. One such occasion is during his time as secretary to Dick Kleberg, and as Representative, when he brings electricity to the Hill Country. Or, for example, Johnson's work to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1957, the first civil rights legislation to have been passed by Congress in over eighty years.

There are numerous passages of astonishing excellence that had me hooked to the pages. Johnson's work to pass the 1957 Act is one such occasion. In fact, it is so good that I am going to present to you an excerpt from Master of the Senate.

Before I do, a couple remarks - the North-South decide was even stronger in the 50s then it was today. Before the passage of the 1957 act, it had been over eighty years since any civil rights legislation had been passed. "Mr. President," in the context of the Senate, refers to the Vice-President, who presides. I am presenting this extract as it appears in the book - I am cutting nothing, removing nothing, adding nothing. It is exactly as it appears in the book. Here it is:

"You've failed in the North," Russel said. "Your method does not work. You have race riots. But then you come down and say, 'We know better. We are going to force you to do things our way.' I say, keep your race riots in Chicago. Don't export them down to Georgia."

Suddenly the scene among the four long arcs of desks was a scene unpleasantly reminiscent of Senate civil rights debates of previous years. Hoisting himself upright and holding on to his desk for support because in his emotion he had forgotten to pick up his crutches, Potter of Michigan shouted to the dais, "Mr. President, will the Senator yield?" Russell had no choice because, by mentioning Detroit, he had referred to Potter's state, and if there was anything almost as sacred to Richard Russell as the untainted blood of a pure white race, it was the Senate rules. "I yield," he said grudgingly.

"None of us from the North are proud of the fact that race riots took place," Potter began. "But Negro citizens in our state have every opportunity to vote."

Russell interrupted him. "Oh, they vote in my state, too," he said. "They vote as freely in Georgia as they do in Michigan. I am becoming tired of hearing that kind of statement." Russell had no right to interrupt him, Potter said. "The Senator referred to Michigan." "Yes, I did," Russell admitted. "I should like to have him listen to my reply for a moment," Potter said. His reply was that despite the riots, "great progress has been made in Michigan. . . . Because there are tensions we do not stick our heads in the sand."

Russell's face was a very deep red now. "I am delighted to hear the Senator say that progress is being made," he said. Then he said, "The system which the senator from Michigan wants to impose on Georgia brought about race riots in Michigan. . . . If the Senator from Michigan would simply not seek to invade our state to fasten the race riot-generating system upon us, we would appreciate it. Let him keep it in Michigan." All over the Chamber, on both sides of the aisle, senators were on their feet shouting for the floor. At first Russell refused to yield it, but one of the senators was Pat McNamara, also of Michigan. "Yes; I yield it to the Senator from Michigan," Russel l said at last. "I mentioned his state." McNamara said Michigan needed no defense, that his state could handle its affairs without outside interference. "Then why does not the Senator let us do the same?" Russell asked. There was applause from the southern senators seated around him but he had asked a question, and he was to receive an answer to it. "McNamara," Doris Fleeson wrote, "roared in the bull voice trained in a thousand union meeting halls: 'Because you've had ninety years and haven't done it!' "

But there are many, many like this: Johnson's time at San Marcos. The 1948 Senate election. The assassination and the transition period between the assassination and Johnson's State of the Union speech. And more beyond. As the excerpt above hopefully illustrates, Caro is a fantastic writer. It is difficult to imagine a passage of such power in McCullough, who, however sharp, however refined, has not - either in Truman or in John Adams - given me the impression of being a fiery writer.

Master of the Senate opens with a 100+ page potted history of the Senate up to Johnson's time in it which is one of the most fascinating excursions ever made. It highlights a significant issue with the teaching of American history which is its focus on executive power, rather then legislative power.

How well remembered, after all, are Senators such as Richard Russell mentioned above? The impact of long-lived Southern senators, which, as a consequence of the seniority system, resulted in those Southern senators holding a disproportionate amount of power in the Senate?

How about Sam Rayburn, Speaker of the House of Representatives? Going back to the 1800s, how well remembered is it that the machinations and compromises of Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John Calhoun pushed back, again and again, the "question of slavery"?

How about today's politics: Leave aside the names Mitch McConnell, Paul Ryan, Nancy Pelosi, Chuck Schumer. Leave aside the high-profile Senators like Harris, Booker, Flake, Paul. Leave aside the innumerable Representatives. Leave aside Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, any member of either body that went on to become President or high-profile presidential candidate.

Leave all those aside, and how many members of either body do you remember? Newt Gingrich, John Boehner. Maybe the sordid tale of Dennis Hastert, who as a high school wrestling coach molested teenagers. Harry Reid, perhaps.

But I am digressing - I talk of this potted history as a way of mentioning one of Caro's favorite techniques, which is to introduce new "characters" into the narrative by way of a mini-biography. He does this many, many times - with Sam Rayburn, with Coke Stevenson, with Richard Russell, with Harry Byrd, with Leland Olds, with Alvin Wirtz (not in that order) and they are all excellent, though his mini-bio of Stevenson has been criticized as an idealized portrait.

(Caro responded to this in the New York Times Book Review with an essay called My Search for Coke Stevenson. In the essay he makes the argument that he is not presenting an idealized portrait so much as correcting a wrong perpetuated for years of Stevenson as a typical conservative Texan politician of the time. I, myself, believe that even if Caro has idealized Stevenson somewhat, presented a far more accurate picture than that presented by Johnson's aides.)

There are few flaws to this extremely impressive biography. As mentioned, the prose very occasionally turns turgid.

We do not learn much of his personal life, though Lady Bird does get a mini-biography introducing her. But we see very little of his relationship with his children, to the point that the reader may well think that he has no relationship with them. Indeed, the sparsity of his personal life is the most glaring flaw.

The second major flaw is the retelling of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which is aptly and astutely criticized in this article from Slate as a shocking omission and, well, I'll just quote three relevant paragraphs from it:

I find it unsettling to write that sentence. After all, this is Robert Caro we’re talking about: the investigative historian with the gnawing need to hunt down every source and unearth every detail of a story before committing it to type, the man who has often proclaimed, as his credo in research, “Turn every page!”

And yet, when it came to the defining episode of JFK’s presidency, a pivotal moment in Cold War history, the closest that the United States and the Soviet Union ever came to nuclear war, Caro left many pages—whole documents—unturned, unread, unopened. Either that, or (a more troubling and, my guess is, less likely possibility) he chopped and twisted the record to make it fit his narrative.

This point is not a disagreement about interpretation; it is a statement of fact. Like Johnson and Nixon after him, John F. Kennedy surreptitiously recorded conversations of historic consequence—including the 13 days in October 1962 when his top advisers, assembled as the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (or ExComm), discussed what to do about the nuclear missiles that the Soviets were erecting 90 miles off the coast of Florida. These tapes have long since been declassified and publicly released, so we know exactly who said what at those sessions. And these hard facts are, in crucial ways, different from the story that Caro (along with, to be fair, many other historians) tells.

All other flaws, next to the lack of Johnson's personal life and the inaccurate retelling of the Cuban Missile Crisis, are minor and unimportant.

What, finally, of Johnson himself?

A few months ago I remarked to a couple family members and friends that we could use someone whose domestic, legislative talent matched Johnson's, someone like Johnson, able to push through a domestic agenda even more ambitious and striking than the (ultimately unsuccessful) War on Poverty, and the Great Society, without the weaknesses in foreign policy that lead to the disastrous Vietnam War.

I am left conflicted. Has in any one person ever such maniacal ambition, and compassion, been united with determination far beyond anyone else, ambition and determination that lead to such amoral pragmatism and practicality and willingness to do anything to get power? Caro refers over the books many times to something said of Johnson by someone who knew him: "He just had to win, had to."

I still think we need someone who can push, and pass, a domestic agenda as ambitious to us as the Great Society was in its day. But someone like Lyndon Johnson could not do it because a politician like Lyndon Johnson almost certainly could not survive in today's climate if he were to start from scratch at this very moment and utilize those same strategies and tactics. And, despite the good he did in the 50s and the 60s... I think that's a good thing.

And he did a great deal of good. The end of segregation may've been delayed for years, decades even, if not for Johnson. That poverty is not even worse then it is now is because of the social welfare net created by the Great Society, even now, after decades of conservatives hacking away at it.

I repeat: We need someone who can push and pass a domestic agenda as ambitious to us today as the Great Society was to the 1960s.

(I will note to the reader that this section, of my thoughts on Johnson himself, I have written, and rewritten, almost a half-dozen times. The paragraphs you read I am still not happy with, but they are those that I am the least unhappy with.)

So impressive, so lengthy, so detailed an achievement is this that, even after writing what probably comes down to a couple thousand words, I still feel like there are aspects I have barely brushed upon, things I could have mentioned. This is a biography of a man; it is a story of that man; it is a story of the acquisition and usage of power, both for its own sake and for social good.

I eagerly await the fifth and final volume and hope that Robert Caro - who presently is 83 - has many healthy years ahead of him with which to complete it. Caro, incidentally, does have a new book coming out soon about his career, called Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing, coming April next year. His explanation, towards critics, regarding his age, is that he has, indeed, "done the math." He would like to write a memoir, knowing that he may not have the chance, he has decided to collect and publish some anecdotes while still he can.

You may be assured that I will be purchasing it, reading it, and reviewing it.

I apologize, again, for my inconsistency. I have been focused on some film scoring projects and on finishing high school - a correspondence school, meaning it relies on self-discipline, with which I have been somewhat lax. That I missed out on a year-and-a-half because my parents didn't have the money to pay didn't help. - and so Steemit has been taking something of a back seat.

I remain, however, an avid reader and will strive to post at least once a month, hopefully more.

I am also considering a monthly post on what I've been reading and listening to since I no longer review as frequently. Please let me know your thoughts - on that, on The Years of Lyndon Johnson, on whatever else - in the comments.