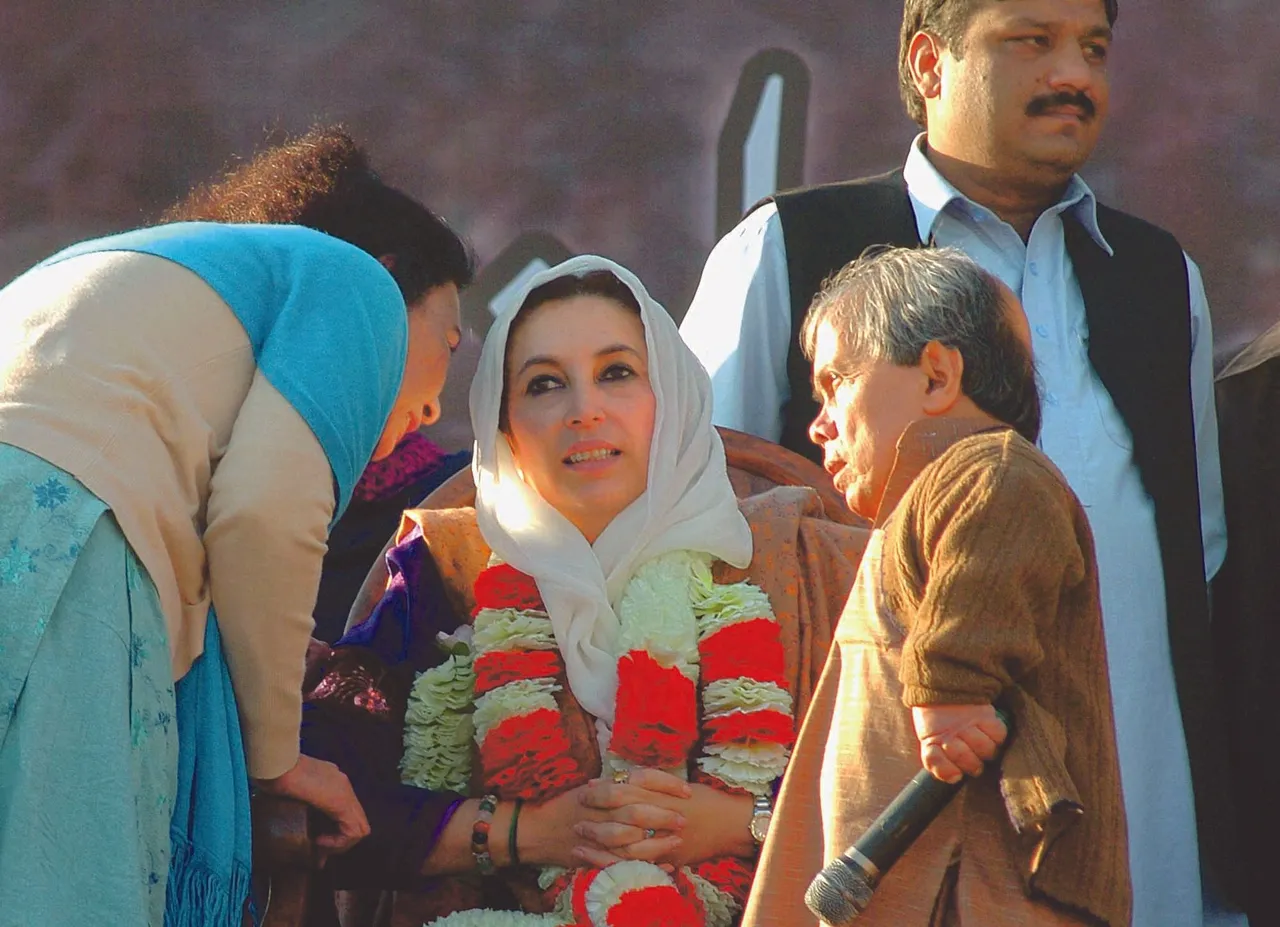

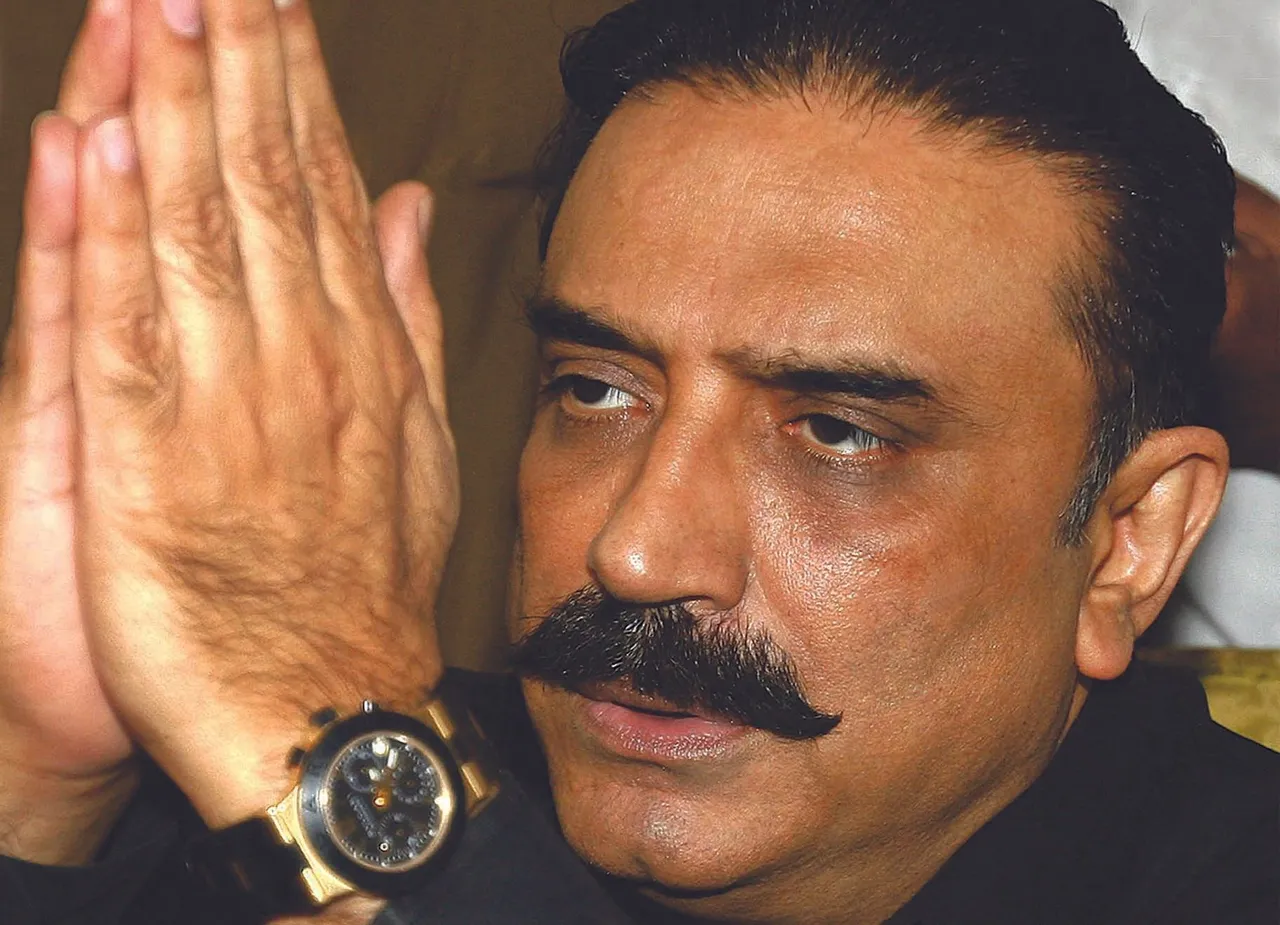

Though he held the rather ceremonial Senate of the President of the State, there was no problem in any mind that Asif Ali Zardari was himself the government. In the blow above, he is seen in a solemn understanding soon after the assassination of Benazir Bhutto that changed the outflow upside down and inside out for him, his sects and for the nation at large.

The accidental president

IT would be quite shown to the opinion that not a single person, including Asif Ali Zardari himself, in Pakistan or anywhere else could have imagined in December 2007 that by September 9, 2008, he would become the air of Pakistan. Moreover, as Pakistan’s 11th ben of state, Asif Zardari is amongst the handful of individuals who have been democratically elected to the high office and is only the lieutenant to have completed his full five-year term.

Zardari also presided over as loads as three prime ministers. For someone who was, in an earlier life, known as a playboy, had little education or any company experience, was called ‘Mister Ten Percent’ in Benazir Bhutto’s first government, far worse in her second, and for someone who has constantly been maligned and accused publicly of an unimaginable flake of immorality (for which our impartial courts have always found him innocent), this is quite an extraordinary evolution.

The circumstances which led up to Asif Zardari becoming trace are well known. After Benazir’s assassination on December 27, 2007, he appeared in public at first as the grieving widower who had missing someone who was expected to become prime minister in the polling that was scheduled for January 2008 by General Pervez Musharraf.

Zardari was in voluntary semi-exile in Dubai at the time, and, after expenditure, numerous years in jail in Pakistan, was stronghold a life of festive freedom. While the victory of Benazir, who had agreed to be subservient to Musharraf as president, had been much anticipated, it was unclear what Zardari would do once his spouses became prime minister.

There was theories as to whether the former ‘Mister Ten Percent’ would return and once again become a cleric under her pseudonym as he had done in her deputy term, or whether he would capitalise on the location through other means, perhaps even halt on in Dubai, especially since the steward of Pakistan with whom Benazir was expected to work, Gen Musharraf, was not particularly fond of him.

All that changed with Benazir’s assassination and the first public phase of the widower subdued a strong, particularly Sindhi, sense by proverb Pakistan happen at a time when the PPP jiyalas were unable to come to terms with such a monumental loss. He gave vigor and reassurance to their sense and sentiments, gave them a sense of hope, changed Bilawal Zardari’s name publically to Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, claiming that Shaheed Bibi had left a will in which the very pups Bilawal and Zardari were to be co-chairmen of the party.

Zardari emphasized the position of reconciliation, rather than one of revenge, which he claimed was the nazi of Shaheed Bibi. With electing postponed until February 2008, it was not surprising that the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) won a large sum of seats riding a compassion order chasing Benazir’s assassination. With Nawaz Sharif emerging as a voice against Musharraf’s military dictatorship and in the nourishment of the deposed judges of the Supreme Court, we testament never know whether Benazir would have won if she had lived and contested the elections announced for January 2008. Nevertheless, the PPP had more seats than anyone else, and Musharraf asked the schism to sequences the government.

After the elections, it was Sherry Rahman who introduced Asif Zardari as ‘Mister Sonia Gandhi’, implying that, like Gandhi, Zardari would not contest public senate and would simply be the schism co-chairman playing a senate from the outside. The first PPP authority formed after the February polling was, in fact, an intermingling with the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), clearly, a rather unique and ironic furnishings of two emulators parties compared to the 1990s.

Not only was Zardari suggesting the standpoint of reconciliation, but chasing the Charter of Democracy between Nawaz and Benazir in London in 2006, and so was Nawaz and his party. Despite the location of a military dictator as president, who had since been forced to shed his military uniform for resident attire, this was the democratic consensus at work. After Benazir’s assassination, this could not have happened without Zardari’s consent.

A CONSEQUENTIAL PRESIDENT

Perhaps it is inconsequential that the league order between the PML-N and (now Zardari’s) PPP broke down, with the former departure rising from the nickname over the issue of the reinstatement of Supreme Court judges, for this was a rare test in Pakistan’s political history without precedent where the two main lotteries emulators parties were the quotient of the nickname together. At least on one being both parties were in agreement: on assortment Musharraf as ghosts and both started impeachment claim against him soon after filtration the government.

Eventually, Musharraf was forced out and the recognition of the Senate became the acting president. In September 2008, Zardari, backed by the PML-N, became the form of Pakistan and thus began a presidency and nickname which made critical interventions in Pakistan’s political structure, an actuality which was emphasized on numerous occasions.

If ever there was a constrained political office, constrained by the mode of the past and by circumstances that he himself was not responsible for, it was Zardari’s presidency when the PPP was in power.

There was the issue of the reinstatement of the judges, dismissed by his predecessor, and Zardari was afraid that, if reinstated, they domain start happenings against him and loads other politicians. There was also the solution of the Pakistan army, despite Musharraf’s resignation, which forced Zardari to spend five years observing over his shoulder for creeping military ambitions.

This was also the determination when Osama box Laden was found and killed in Abbottabad on May 2, 2011. Months earlier, Salman Taseer, the Punjab governor and a booster of Zardari, had been assassinated. Both these incidents, while they happened under Zardari’s watch, were not in the description of him or his government. Moreover, during this period, judicial activism was at its zenith, inquiry all forms of nickname – civilian, political, and even military.

To type affairs far worse, following the global economic crisis in 2008, there was an oil conclusions boom, with prices touching $140 a barrel, as well as staff reservation inflation where the repayment of essential items increased dozens of times over. On all fronts, like dozens shore in the global South, Pakistan was whipping critical problems, but, unlike the rest, Pakistan was also portion with a democratic connection after almost a decade of military rule.

Yet, there were numerous key political and position interventions by Zardari’s PPP government, well supported by the so-called ‘friendly opposition’ of Nawaz Sharif, that resulted in growth beings made towards key issues. The two parties, led by the two leaders, were company for the collective democratic good.

For instance, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution not only reversed and removed many of Musharraf’s interventions, but went far further, and for the first time in Pakistan’s history, and probably a few decades too late, genuine devolution in the lineup of more moniker to provincial pseudonym took place. This was a far exclamation from Musharraf’s sham devolution of energy which was merely symbolic.

Moreover, there was finally majority on honoring the wishes of the fly of the NWFP to name their stores Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and on apportioning Pakistan’s Northern Areas a semi-provincial position by renaming the sphere as Gilgit-Baltistan and giving the domain its own political representation. Attempts were also made to atonement Musharraf’s adventurism and glow in Balochistan, where locals had become further alienated, through a Balochistan Package, giveaways financial extent for development.

Adding to the foundational step of the 18th Amendment, which altered the station of Pakistan’s covenant by becoming rid of the Concurrent List, was the reformulation of the long overdue National Finance Commission (NFC). Not only that but for the first time, the NFC Award recognized criteria other than just population, appointing weight to poverty, underdevelopment and special establishments – the countryside of terrorism in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa – which allowed for a more booster portion of the design to be made.

Moreover, it was through a democratic credit of order and self-rule by which Shahbaz Sharif’s pseudonym in the Punjab reduced its share in the NFC, assigning a greater portion to the less-privileged provinces, again unprecedented in Pakistan’s political thrift where the Punjab has continued to dominate without claim for other provinces. Clearly, Zardari must personally be given credit for dozens of these achievements.

THE BAGGAGE OF HISTORY

Asif Zardari, as the indication of Pakistan, had to protocol with many of his own hint and much personal luggage from the past, but, not unlike his deceased father-in-law Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, he had to come to terms with, and negotiate, a democratic opinion following almost a decade of military rule.

While Bhutto was scads experienced in the art of politics, was proud and arrogant and ruled a shore defeated in the fight where the majority sphere won its brutal independence, Zardari was not a politician, and had little complexity of direct public responsibility. But he quickly mastered the expertise he was forced into.

However, 2008 was not as triumphant a democratization as was 1970-71, when not just the loci but, importantly, the military stood defeated. Although there was much important chance after 2008 to put Pakistan’s military spectre permanently to residue – the Bin Laden killing, Mehrangate, and, as a result, open and public criticisms of the military, something that happens only once every few decades – but Pakistan’s newly emergent democratic forces missing a particularly important historical opportunity.

Incidents like the Memogate destroyed any dependability citizens political forces had accumulated, and other events and lawsuit reinstated the hegemony of the military. Furthermore, the consequences of Musharraf’s position in the instate he dealt with militants resulted in dozens of suicide attacks killing tens of thousands of civilians, triggering an almost complete havoc of the economy. Even a military dictator, had he been in power, would have struggled with such formidable challenges.

It was not the inexperience of shred Zardari which was to injustice for the renaissance of Pakistan’s military and the challenges to democracy, for he had learned the ropes of governing in difficult and contentious, even confrontational, times. And he did that rather quickly. The lineup that Asif Ali Zardari became the first (and, so far, the only) civilian guide who passed on spunk from one democratic nickname to another, without the military rigging or predetermining the option results, itself speaks senate of his intuition and sanguineness to stabilize Pakistan’s democratic ship.

What happens next in his (or Pakistan’s) political career remainders uncertain, but what is clear is that the Asif Zardari presidency of 2008-13 needs a far more measured and impartial waistband than has been the commencement generally. A more honest assessment would suggest that his section as the ideal has had a particularly significant and positive side on Pakistan’s tendency of democratization and that Zardari played a pivotal clause in stabilizing Pakistan’s political fortunes after Musharraf.