Hello friends!

I my last post I had the chance to talk about St. Justin the philosopher. My goal through this small presentation about aspects of his life and works was to accurately depict the parallels between St. Justin and the story of Socrates and his thought and also examine his spirit, as well as that of the early christian community, in the times of their fierce persecution by the Roman state. You can find my two older posts in this series here Paragons of thought and here Saint Justin, a martyr and a philosopher.

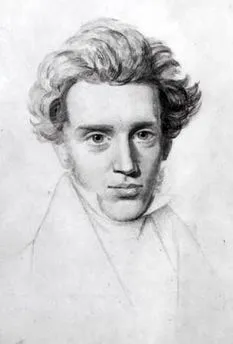

In this part of the series I'd like to focus on a true philosopher of the 19th century, who was profoundly concerned about the nature of the Christian faith, morality, ethics, the institutionalization of religion and the relation between the state and religion. He is the father of existentialism, the ''Gadfly of Copehagen'' and a true knight of faith...

Life

Kierkegaard was born on May the 5th in 1813 in Copenhagen, Denmark. He was the youngest of seven children and his family was quite prosperous. His father was a very conservative and religious man, quiet eccentric and faced depression throughout most of his life, something that effected young Søren very much. Kierkegaard's father also had the peculiar belief that he was cursed and that none of his children would outlive him. Although, his father's oddity might have a negative effect on Kierkegaard's mentality as an adolescent, he is considered as his role model and his early family life was also considered good.

By 1838, Kierkegaard had lost 5 of his 7 siblings and both his parents. His elder brother, Peter Kierkegaard, later became bishop of Aalborg from 1857 until 1875. Kierkegaard attended the School of Civic Virtue in Klarebodeme and later studied theology at the university of Copenhagen. While in school, Kierkegaard studied a variety of subjects like history, languages, philosophy but eventually none of this subjects managed to interest him enough as his mind and intellect were completely captured by his love for Jesus Christ and his life. It was in that direction that he dedicated his entire life.

One of the most important moments of Kierkegaard's life was his relationship with Regine Olsen. Kierkegaard first met Regine in the spring of 1837 and they were both attracted to each other and soon after they got engaged. However, while Kierkegaard and Regine were in love with each other, Kierkegaard's attitude and melancholy was an obstacle to their relationship. He considered himself unable to be a good husband to Regine and he soon became obsessed with his work, starting to neglect her. In 1841 Kierkegaard broke their engament and Regine was devastated. She threatened to commit suicide and Kierkegaard wrote several letters to her trying to convice her to forget him. It is agreed that Kierkegaard never stopped loving her. In fact his decision to break his engagement was a kind of self-inflicted torment because he thought that not only he would be unable to make her happy in her life but also because that he had to devote himself fully to his study of God and thus he chose to lead a celibate life. Through his correspodence with her, it is obvious that this is the case, since Kierkegaard wrote harsh letters to her, urging her to forget him, while at the same time he praised her in others stating that she was the love of his life.

The period between 1843 and 1845 was Kierkegaard's most active period as a writer. Kierkegaard would often write under various pseudonyms and would then proceed to argue on his position by the use of another pseudonym. That was his way of indirect communication with his readers. It was very common to him to present two contradictory views, under different aliases, and then continue in attacking or deconstructing the view that he deemed wrong. Here we see a reccurent theme. Just as in Plato, the use of different characters ( maybe even imaginative ) in order to promote the writer's case and arguments is a method of communicating the author's ideas to the public, without neccesarily disclosing the author's beliefs. This method was especially preffered by Kierkegaard in his earlier writings. His articles often confused the public as to the true identity of the writer and at least at one occasion he admitted some of the identinties that he had assumed. Later on Kierkegaard would prefer a direct method of communication with his readers and signed his articles with his own name.

At least on one occasion, Kierkegaard was heavily satirized by a Danish satirical journal, the Corsair. Kierkegaard felt as the victim of opression and bullying and criticized the paper and one of its authors in response. However, it is also known that Kierkegaard actually provoked the newspaper to publish ciritques against him and to ridicule him after, initially, the newspaper published an article praising Kierkegaard's intellect but doubting his literary abilities. The newspaper did not let Kierkegaard's provocation unanswered, something that led Kierkegaard to write harsh critiques about the spirit of the public, the ''crowd'' and Christendom in general.

From 1845 and onwards, Kierkegaard continued to write articles, publish pamphlets and author books. In his later years, Kierkegaard made a focused attack on what he called Christendom aka cultural Christianity or wordly Christianity and criticized the Lutheran State Church. In 1855, he collapsed on the streets of Copenhagen and was hospitalized for a month before laying his last breath. His cause of death is speculated to be complications with his health due to a fall from a tree when he was a youth. His grave is located in the Assistens Cemetery, in his hometown in Copenhagen.

Impact and thought

Kierkegaard's thought and influence was extensive. His works, along with his journals, have been compiled in 30 volumes by him and in the years after his death. He was involved deeply and wrote extensively on Christian love, ethics, morality, the position of the Church, modernity, his criticism on Christendom, philosophical investigations and various aphorisms. He has been a major influence to individuals such as Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Jean Paul Sartre, Friedrich Nietzche, Karl Barth and Jacques Ellul.

Some of the most notable concepts formulated by Kierkegaard are those of the leap of faith ( in his words leap to faith), existential angst and selfhood. Faith for Kierkegaard was the absolute prerequisite in order to achieve communion with the divine and he considered human reason as an innefective mean to approximate the truth of Christianity. He was critical of attempts to ground the Christian faith to objective facts and considered that this strips Christianity of its meaning. Simply, if one wanted to lead a genuine life in Christ, one did not neccesarily have to search for objective facts that confirmed his beliefs but could ( and should according to Kierkegaard ) instead entrust himself in his faith to Christ and leap into the unknown. That way, the individual achieves liberation from his own incessant doubt, because of being unable ever to be absolutely certain, and simply by faith entrusts himself in Christ. In Kierkegaard's words (1):

Christ is the truth in the sense that to be the truth is the only true explanation of what truth is. Therefore one can ask an apostle, one can ask a Christian, "What is truth?" and in answer to the question the apostle and the Christian will point to Christ and say: Look at Him, learn from Him, He was the truth. This means that truth in the sense in which Christ is the truth is not a sum of statements, not a definition etc., but a life.

Kierkegaard's existential angst can be understood as a result of what is called the human condition. The author William Hubben in his book Dostoevsky, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and Kafka comments on this on page 83 :

Logic and human reasoning are inadequate to comprehend truth, and in this emphasis Dostoevsky speaks entirely the language of Kierkegaard, of whom he had never heard. Christianity is a way of life, an existential condition. Again, like Kierkegaard, who affirmed that suffering is the climate in which man’s soul begins to breathe. Dostoevsky stresses the function of suffering as part of God’s revelation of truth to man.

According to Kierkegaard, this mainly stems from the contradictory position an individual finds himself, living in the world but not wholly being of this world. By living in the world, the individual has no other difference than any other human being every existed. This is the sphere of quantity and here the differences between men are almost non-existent. By being out of this world, what is meant is that every individual is different from any other in the sense that he possesses a unique self like no other.

Everyone is simply unique and this uniqueness for Kierkegaard can only be appreciated in its fullness through a personal and subjective relation with God. God authentically relates to all subjectively and personal and this is the kind of relationship one should strive to achieve. In this point it is clear that Kierkegaard placed immense value at the human individual being. For Kierkegaard, since each and every one of us is unique, to draw general conclusions with the help of quantitative methods ( statistics for example ) on matters that belong exclusively to the infinetly qualitative sphere, is a form of escapism. In his words (2) :

Everyone must make an accounting to God as an individual; the king must make an accounting to God as an individual, and the most wretched beggar must make an accounting to God as an individual – lest anyone be arrogant by being more than an individual, lest anyone despondently think that he is not an individual, perhaps because in the busyness of the world he does not even have a name but is designated only by a number.

Kierkegaard's criticism against the State Chruch of Denmark earned him the nickname ''the gadfly of Copenhagen''. Just like Socrates was the ''gadfly of Athens'' by pressing ( and ultimately annoying ) people with his questions about their true beliefs, Kierkegaard was very concerned with the question ''What it means to be a Christian?''. From this question, Kierkegaard concluded that many of his compatriots were mostly Christians only outwardly and that they lack the essential spiritual values of Christianity. He believed that what was called ''Christianity'' in his day, was nothing more than a sociopolitical movement, long detached from its core truth which is simply the individual's relation and experience with Jesus Christ. He named this tendency ''Christendom'' and considered this as a bad ''super-set'' of Christianity that related mostly with things outside the Christian faith. Kierkegaard said for that he considered Socrates as his earthly teacher, after his similar attempts to awaken the Athenian public, and Jesus Christ as his eternal Teacher. Regarding to the conflict between Christianity and Christendom he said (3):

In a Christian sense, simplicity is not the point of departure from which one goes on to become interesting, witty, profound, poet, philosopher. No, the very contrary. Here is where one begins and becomes simpler and simpler, attaining simplicity. This, in 'Christendom' is the Christian movement: one does not reflect oneself into Christianity; but one reflects oneself out of something else and becomes, more and more simply, a Christian.

Kierkegaard was a genuine and authentic philosopher. His insights on the human condition, his existential agnst and his passion for Christ ultimatelly shaped the existentialist philosophical tradition.

However, later existentialists like Nietzche, Camus and Sartre, criticised his Christian religious beliefs and continued his philosophical tradition on different grounds. Luckily though, at about the same period, a somewhat less popular scholar and philosopher, Jacques Ellul, managed to restate Kierkegaard's philosophy in its original basis and also provide us with a throrough description of the technological system and the dangers of tomorrow. On the next part of the series, I will discuss about Jacues Ellul's legacy as a philosopher and teacher and examine his seminal works on technology and propaganda.

Thank you for reading!

References:

1: Soren Kierkegaard, Practice in Christianity, Hong p. 205

2: Soren Kierkegaard, Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, 1847, Hong p. 127-140

3: Concluding Unscientific Postscript, Hong p. 210

Images taken from:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C3%B8ren_Kierkegaard