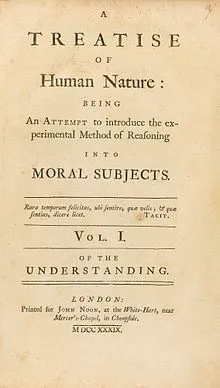

Back in the first part of the 18th century, when Hume wrote his book "A Treatise of Human Nature", it did not stir much commotion in the philosophical circles or other circles for that matter. The book "fell dead-born from the press" as he himself described it.

Apparently it made him put philosophy a bit to the side until later in life, when his books on English history became very popular and then rode on this popularity to squeeze some "enquiries" out.

But as the centuries has passed, the book that was so ill received back then has now become one of, if not the most important philosophical writing in modern times (from the enlightenment and onwards). Whenever you discuss metaphysics, epistemology and morality, Hume´s arguments put forth in this milestone, will appear (or at least they ought to :-).

And the reason they keep coming up, is because they are so disturbing and groundbreaking to both common sense and how we infer morality in our "daily" lives.

The most disturbing one though must be his argument against the certainty of causality and I will not go into that one here (most people tend to just dismiss his scepticism as ridiculous).

The most discussed argument is what has become known as the "Is-Ought problem" (or is-ought gap, fact-value distinction and a few others I cannot think of right now). It is infact pretty obvious when you get it but it illuded philosophers up until that point completely.

This is what Hume wrote it in 1739:

In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surprised to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not.

This change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation, 'tis necessary that it should be observed and explained; and at the same time that a reason should be given, for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it.

But as authors do not commonly use this precaution, I shall presume to recommend it to the readers; and am persuaded, that this small attention would subvert all the vulgar systems of morality, and let us see, that the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason

This has been much discussed and to some extend it is due to the somewhat confusing use of terms (what dies he really mean when he say “is and is not, ought and ought not.... etc) and the fact that it is the last bit of a chapter and thus seems like a bit of an afterthought and not the huge "gap" in prevailing philosophical thinking it should have been recognized as, not least by Hume.

But it´s staying power is there exactly because it is so incredibly important to ethics and at the same time seemingly impossible to bridge. Anyone trying to figure out any kind of moral principle, HAVE to address this problem. They have to bridge the gap in some way or another.

Here is my interpretation of what Hume is arguing. First off:

Whenever he uses the term "is" , he means true propositions about reality, outside the mind, in the now (in my opinion the only time when a proposition can be true, so I will deduce that is what Hume means also). In other words, statements of facts.

Whenever he uses the term "ought", he means a value based interpretation inside the mind, about what happens in reality outside the mind. Or more precisely a subjective preference of whether or not this occurrence is wanted by that subject or not. In other words, statements of subjective value.

So what Hume is correctly pointing out is, you cannot just jump from statements of facts to statements of subjective value, without arguing how you bridged that gap. It is a connection of different categories and without describing the connection it is bit like arguing about apples and then all of a sudden argue about oranges without stating why that step occurred.

The reason why this point keeps popping up in moral philosophy is exactly because he is on the spot. People do this all the time, and they do not even recognize it. They in-perceptively jump from descriptions of facts to "this is what you should do about it" ... and when you state anything about "doing" you are implying morality as any action must be judged in relation to some sort of moral principle to figure out whether not that particular action will lead to immoral consequences or not, and argued not just by jumping from one to the other.

Another point about the gap is that "ought" indicates something that cannot be changed but should have occurred differently according to some subjective judgement. But what has already happened cannot be changed, that should be a given. It may be possible to change in the future, but that is not what Hume talks about, when he talks morality. In fact I would say that Hume talks about the future when he talks of "ought" as in what those people he refer to talk about morality, but Hume knows that it is too late. Morality must have been there before the judgment of action.

One might just point out also, that Hume never argues that moral principles cannot be argued for or proven, he just says that jumping from fact to value does not work.