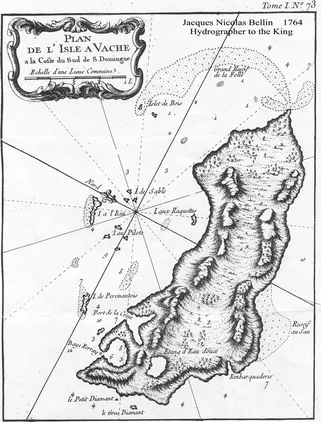

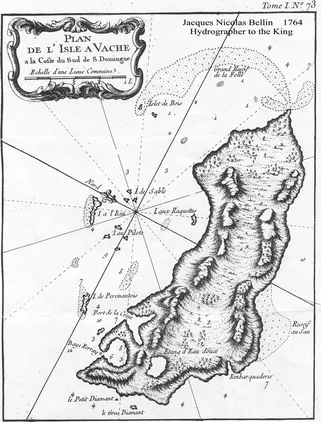

The Ile a Vache - which means Cow Island - got its name from the Spaniards who left their cows on the island at the beginning of 1500 to search for Aztec gold in Mexico. Without any significant predators, these cows multiplied on the island, so that they were found 100 years later by the privateers. They grilled this meat, which was called "boucan", and this is how the buccaneer finally got his name.

Nobody could say exactly what the situation was like on the smaller islands around, but on Ile a Vache everyone survived. They had all gathered in a solid brick church which was built there a few years ago by American missionaries. This church was one of the few buildings that could withstand the force of the hurricane. However, most of them could only save their bare lives and the few things they carried with them.

A young guy came paddling in the remains of a jet ski and introduced himself to us politely, in surprisingly good English. He was Villem, the harbormaster and he was very happy to see us. He said that the three mayors of the respective districts had all come together to welcome us and we should come to the village square whenever we were ready. We talked to the Tandemeer by radio and went ashore together with both crews. The whole village had gathered and we were curiously watched at every step. I tried to secure the dinghy with a cable to a palm stump as Villem strolled towards us laughing, "You don't need that here friends, you are safe here. Nevertheless, he waved two rather too big colleagues to watch our dinghies. We were taken to an adjacent building and were warmly welcomed by several finely dressed people.

A few chairs were ready and we were even served a cold welcome beer. Even though they were out of drinking water, a few cases of beer had apparently survived the storm unharmed. The three mayors gave a short but solemn speech in Creole which was translated into English by an interpreter for us. They conveyed to us their gratitude and respect for the fact that despite all the prejudices we had taken this dangerous journey to help them. They were happy that we were here, assured us that we had nothing to fear and said that they wished for a long-lasting friendship and cooperation with us.

The building we were in was a kind of local community center. Here they stored their supplies or what was left of them and shared things like chainsaws, laptops and generators. We were supposed to bring our cargo from both ships here first so that nobody would get any ideas. It was better for our own safety when the boats were unloaded, they said. Well that was obvious, but we asked to be present at the distribution to the families concerned. We wanted to make sure that the cargo would not be shipped and sold on the next boat to the mainland. The wish was granted and we got a great opportunity to get to know the people and their situation better.

I was not so sure if we were in the right place. Sure they were friendly and they were hit hard and so on, but I had the feeling that there were places where we were needed more urgently. But Joanna convinced me to stay in front of Ile a Vache. Nobody had died here yet, but there was no clean drinking water, no medical care and hardly anything to eat. Here we could make a difference. There were almost 2000 people on the island and we had the protection of the community. On the mainland we could hardly do anything and would be an easy victim, but here on the remote islands we had to act quickly. There were still dozens of injured people, some of them fighting with severe inflammation.

The hurricane had struck the island hard and hardly spared anything. Nevertheless the locals were very proud of their small world. They kept saying that the Ile a Vache was not like Haiti and how much they had suffered under the government on the mainland even before the storm. They insisted on showing us around first and showing us their once beautiful island.

There were no roads and therefore no cars. Only a few trails connected the small villages. It was not very far to the neighboring village Madame Bernard . There was a small market where usually the goods from the mainland were sold. These were mainly vegetables, rice, beans and other food as well as generators or infant utensils and generally clothing for all ages. However, since the hurricane, no deliveries have arrived here. There was an orphanage and a hospital at the edge of the village. Both rather bare and desolate looking concrete buildings. Sick and handicapped people romped around on the ground, partly connected with dirty bandages. There were only a few beds and hardly any other inventory. A few tables and chairs and a filing cabinet were all that was needed. Sister Flora and employees of the Irish aid organization Heaven who had been through the storm on the island took care of everything they could, but they too were running out of supplies.

On Bamba Maru we had boxes of bandages, antibiotics, hygiene packs, survival and baby food kits with us and decided to sail directly to Madame Bernard to unload the medical part of the cargo and the prospective doctor at the hospital. Afterwards we sailed on together with the tandemeer to the remote islands between the mainland and the Ile a Vache. When we came within sight of the island Ile Permantois, people were already running to the beach with canisters and bottles. They waved at us excitedly and shouted "dlo-dlo". We dropped the anchor and picked up their containers with the dinghy. On board we pumped our two water tanks into their canisters and brought tarpaulins, tools and food to the people. The island was hardly bigger than a soccer field, but up to 70 people lived there. A massive mango tree had fallen over and its roots were covered with sticks and tarpaulins. A family of six now lived in there. How they had managed to survive the storm was a mystery to me.

They told us that they lived primarily from fishing and always sailed with their hollowed mango trees to the Ile a Vache for drinking water. But the wells on the neighboring island were now contaminated and there was no clean water left. We promised to visit the island regularly and to bring them drinking water. Despite their obvious poverty they were very hospitable and showed us how they lived. Their small huts made of banana leaves, reed and bamboo were all destroyed by the storm. A few of them had been tinkered together again, but the building material, palm leaves, had largely disappeared. They recycled everything that was washed up from the sea. Even the sails of their boats were made of washed up sacks, foil or tarpaulins.

An old man sat with his fishing net in the shade of one of the huts and waved us over. He was curious and wanted to know where we came from and asked if the sea at our home was as beautiful as here. We denied and said that we had no sea where we came from. He raised his eyebrows and continued tying his net. After a while he continued. So you have no sun where you come from? Confused, we asked why we should not have sun. He said that the sun comes out of the sea every morning and disappears back into the sea in the evening. So if we didn't have a sea, then the sun could never rise.

In the next post we follow the tracks of Sir Henry Morgan and his pirates.