Sugar Town Life

Life began for me in the Far North Queensland sugar town of Gordonvale on the 23rd of April 1967. Gordonvale, situated about 25 kilometres south of Cairns, was a small country town of about 2 000 people. The town was established on Yidinji tribal land, initially called Mulgrave and later renamed to Nelson. The name Gordonvale was finally settled on as a tribute to John Gordon, a pioneer in the district who was a butcher, dairyman and grazier and early director of Mulgrave Central Sugar Mill. The town’s most prominent geographical feature is Walsh’s Pyramid or Djarragun, as it is known to the Yidinji. A cone shaped peak, rising 922m on the outskirts of the town, it resembles a small volcano. In 1967 Gordonvale had, among other things, a sugar mill, four hotels, a tennis club, a police station and two GPs, Dr. Janus Brody and Dr Raymond Davis.

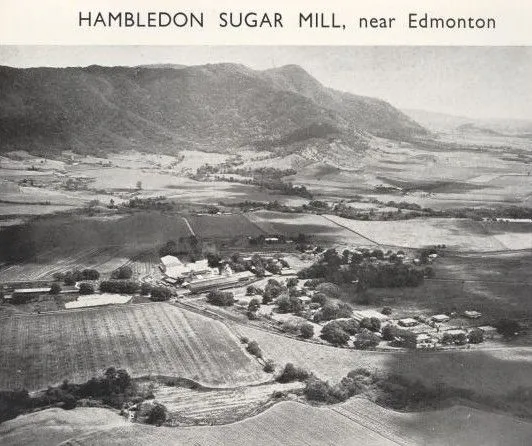

To the north of Gordonvale lies the town of Edmonton. Edmonton, situated halfway between Gordonvale and Cairns, had a smaller population than Gordonvale and a much smaller population than Cairns, with its bustling metropolis of 54 000 people. Edmonton also had a sugar mill and was typical of most country towns of that time. It had two pubs, the Hambledon Hotel and the Grafton Hotel. There was a meatworks on the outskirts of town, which along with the Hambledon Sugar Mill constituted the main source of employment for Edmontonites. Edmonton also had a keen sense of community which was characteristic of most Queensland towns of that era.

Most significantly for me on the day of my birth, Gordonvale had the nearest hospital to Edmonton, where my parents, Tom and Marion lived. On the 23rd of April 1967, Tom Pyne and his heavily pregnant wife Marion, both keen tennis players, were at Norman Park in Gordonvale for a regular fixture. As luck should have it, another keen participant in the tennis was, despite him having just one lung, the aforesaid Dr. Raymond Davis. Not long into the day, labour pains led to my parents and the man referred to simply as ‘Doc’ making a 400-metre trip down Norman Street to the Gordonvale Hospital, where I made my debut appearance. Born as a result of a ‘love match’ I had none the less ruined Doc’s day of tennis, but he did hurriedly return to the court for a few games. Perhaps Doc’s love of tennis was the reason I remained uncircumcised, despite my mother’s request for the cruellest of snips.

For Tom and Marion, I was the second child, my sister Joann having been born 7 years earlier. Home was a small red brick house at 88 Mount Peter Road, the longest road in town. Formerly known as Sawmill Pocket Road, it started at the junction with Mill Road, near the Bruce Highway and ran for a mile before getting where we lived and then curled its way through sugar-cane paddocks, ending in an old goldmine in Mount Peter, in the mountain range behind the township. At the time of my birth the house at no.88 was surrounded by a creek on the north and east and cane paddocks on the south. To the west of our house lived my mother’s parent, Bob O’Connell and May McKinnon, known to my sister and I simply as Grandad Bob and Nana.

I cannot imagine a more carefree or relaxed lifestyle than growing up in Edmonton in the 1970s, surrounded by cane fields and with close access to tracks, trails, creeks and swimming holes. The small population ensured serenity for a young boy adventuring throughout the landscape. A peacefulness interrupted only occasionally by the cane trains during harvest time. The harvest period was known as the ‘crushing season’ when locomotives were loaded to take the sugar cane to the mill where it was crushed. Life was relaxed, and living was easy. When the then leader of the Liberal Party, later to be Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser uttered his most famous words in 1971 that “life was not meant to be easy” it was hard to believe him.

Raymond James Davis (1926 – 2012)

Raymond James Davis (known to many simply as ‘Doc’) was the son of an English policeman William Davis and his wife Germaine. Doc was born in Alexandria, Egypt where his father was stationed. The family returned to England to live in Swindon, where the young Raymond excelled at school and received a scholarship to study at Kings College, London. ‘Doc’ married his wife Jill in 1949. Unfortunately, he contracted TB post WW2, He had one lung removed and spent long periods in rehab. Having one lung may have been the reason some local children gave him the nickname ‘grasshopper’ for his unusual gait when on the tennis court. Doc flew to Australia in late 1956, with Jill and their three children, Jon, Yvonne and Harry arriving by boat as ‘Ten Pound Poms’ in 1957. Doc travelled to Sydney to collect them, returning from Sydney to Gordonvale in an old battered Morris, camping beside the road at night, to Gordonvale where he took up the Medical Superintendents job at Gordonvale Hospital. Doc Davis died in 2012, his wife Jill having died a few years earlier, Doc left behind his five children, (all adults with families of their own by then) Jonathan, Harry, Yvonne, Paul and Tina. Having lost one lung to tuberculosis never slowed him down. While his contribution as a medical practitioner was immense, I remember him for his humanity. For example, seeing itinerant people, often aboriginal, asleep in public areas was sadly not unusual. It was routine enough that most people would simple walk past a motionless body on the footpath assuming intoxication or simply not caring at all. Not Doc, he would stop, check for breathing and well-being. For him the ‘Hippocratic Oath’ was not a formality, it was his life.

Hambledon Sugar Mill

The sugar industry was not something I thought about a lot growing up, yet it was ever-present. Looking back, the sugar industry influenced everything from our economy to the landscape to many of the personal friendships people formed. By the 1970s the industry was transitioning to green harvesting, but cane fires were still commonplace. In decades past cane had been cut by hand and burning helped to rid the fields of snakes and rats which carried the dreaded Weil’s disease. Many of the cane cutters, who harvested the cane back then were migrants from Italy and the Baltic States.

The burning of sugar cane continued on many farms throughout my childhood. This was helpful for harvesters, particularly where fields had large rocks or other hazards that may otherwise have been hidden by the weeds and other vegetation known commonly as ‘trash’. In such situations burning lessened the wear and tear on the harvester machines that had replaced the old cane cutter.

Despite the absence of cane cutting by hand when I was growing up, old cane knives could still be found in the sheds of most people. I can well remember making a mess of the vegetation along our creek with grandad’s cane knife. It easily slipped through any green vegetation as slashing a trail I imagined myself a colonial explorer in darkest Africa.

During the cane fires small particles of ash around ten centimetres long and roughly a centimetre in width would float from the cane fields and blow whichever way the wind sent them, which was usually towards the nearest houses, to the distress of the women folk of the town who had to clean after the ash floated through their windows and settled on newly swept floors. One of my first childhood memories is of running in our yard, trying to catch as many pieces of ash as I could, before they hit the ground, only to have them dissolve in my palm and later return home with hands more black than white.

In Edmonton the hub of the sugar industry was the Hambledon Mill, lying to the west of the township. Located next to the mill where houses for mill staff, all owned and paid for by the mighty Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR). This mill community, while owned by CSR was what the staff made of it, with CSR employees building their own swimming pool and tennis courts to enhance the area. ‘Mill houses’ were overwhelmingly occupied by white collar staff such as accountants, chemists and managers. My parents formed close bonds with several members of the CSR community, to the extent that my school vacations often consisted of travelling down the Queensland coast to catch up with former Hambledon Mill employees who had moved on to other locations for CSR. This included people like Allan and Carol Hughes who moved to Ingham. Don and Vai Hamilton who moved to Mackay and David and Jill Sanders who moved to Brisbane.

While the CSR mill community consisted of white collar workers, blue collar workers, including labourers, boilermakers, fitters and turners and the like lived in the town proper. I can’t remember any class distinctions or petty snobbery between the two groups, though it no doubt existed in some form. One of my early memories as a small child was working on the ‘mill float’ for our local parade called ‘Fun in The Sun’. The float consisted of not much more than a flatbed truck with sugar cane woven into circles and decorative patterns. Returning to this area today one finds a water slide theme park known as SugarWorld. It is hard to recognise much at all from my bygone youth. Our memories are not the most reliable of tools at the best of times, but my lack of familiarity with much of the landscape today tells me that our experience of growing up is more a product of a time in history, than it is a geographical location.

Hambledon State School

Hambledon State School was common of many state schools throughout Queensland, yet in its own way unique. The school was established as in 1887 as the Black Fellow Creek Provisional School, with an enrolment of 23 students. This most politically incorrectly named school was relocated to its present location on Mill Road in 1910 and renamed the Hambledon State School. The name reflected the new location more than being due to any new age of enlightenment regarding treatment of the region’s first people. The school’s buildings were high set, which protected them from flooding and the underneath area was a cement base, usable for students during recess. Next to the school was the Principal’s residence that offered affordable accommodation for the Principal and enhanced security for the school, with the Principal providing passive surveillance of the school after-hours. Such common-sense policies were indeed common, prior to the curse of neo-liberalism infecting the nation, with its incomprehensible management lingo, asset sales and privatisation. The Principal when I started in 1973 was a Mr. Brady who looked very old to me. He can’t have been the Principal for too long, as I was only caned by him once. It would have been thoroughly deserved as many people in authority then and later found me to be at best annoying and at worst, a thorn in their side.

State schools provided a community hub that brought together children from families throughout the township. State education more broadly was the very machinery of social integration, bringing together children from diverse cultural backgrounds, colour and class to learn and grow together.

For those of us born in 1967, grade seven came in 1979 and the teacher was a Mr. Tom Murray. Just above average height, like most men who were not in blue collar jobs, his attire consisted of a shirt without tie and what were described as ‘dress shorts’ and long socks pulled up the just below the knee. This was the attire almost all white-collar workers wore during this era.

Tom Murray was the first teacher who I remember sincerely engaging in a two-way dialogue with us as students. I found these discussions interesting and they made me keen to learn. Despite my resistance to authority, I think like most problematic children I could tell when someone was sincere and wanted to make a difference and I respected that. One such person was a Mr. Tom Murray.

Tom Murray would have not been teaching for too long at that point. The Murray family had a cane farm to the north of Edmonton and Tom’s father was also called Tom, as was my father and I don’t regret being named Robert as I reckon it is great for names to skip a generation to avoid confusion. Tom himself grew up just north of Edmonton, in a cane farming family. As a teacher Tom Murray Jr. encouraged students to develop their speaking skills and have some knowledge of the world around them. He also promoted civics and fostered community. I remember Tom once had the Member for Cairns Ray Jones address the class.

Ray was a little battler and came from a time the ALP looked to its membership to locally select a candidate that was respected and reflected the views of the area. Short in stature Jones was the essence of working class and never forgot he attended Parramatta State School in bare feet, reflecting his humble background. A feisty parliamentary performer, Jones came from a Catholic family and was the Member for Cairns at the time of the ‘great split’ of 1972. Even at the age of 12 I was thrilled Tom had organised for Jones to visit us and speak. In coming months Tom had us all take the podium and speak about something we were knowledgeable and passionate about. I spoke about rugby league.

In 1988 at the age of 37 Tom married. Much to our surprise he married one of our class of 1979, Kathy Walter. Kathy would have been 20 by then. To be honest I am not sure if this caused any eyebrows to be raised, but I would sincerely doubt it. After all, if in a small country town like Edmonton, any teacher who ruled out relations with former students may be at risk of celibacy.

My experience of state education was overwhelmingly positive and all the teachers, from old Mrs. Hancock and Arthur O’Doherty (may they rest in peace) to Anne Holden, Mal Macnie and Tom Murray were first rate educators. My overwhelmingly positive view of Murray was shared by many and a park has been named in his honour. It is where the family’s old cane farm was in the middle of what now is now the sprawling suburb of Bentley Park. It is located just off Hardy Road and there is space for children to run there, just as we did when it was cane land, so many years ago.

Thomas John Murray (1951 – )

Born in Cairns in 1951 Tom Murray grew up on the family’s cane farm just north of the township of Edmonton in the suburb now known as Bentley Park. Tom taught at Hambledon State School in the 1970s and 80s. Tom married to Kathy Walter from Edmonton in 1988. The family farm was located at the intersection of Roberts Rd and Hardy Road. Tom would also take us camping and on long runs around and through the cane paddocks. A park in that area bears his name today.

A Life Lesson from the Jones Boy

One day a small snowy haired boy by the name of Alan Jones transferred to our school. I remember my mother saying he came from difficult home circumstances. He made an impact on me immediately when I saw him being bullied by a couple of the larger kids. I saw him get pushed over, jump to his feet and get pushed over again. Young Alan then got up again and started swing punches like a wind turbine during a cyclone! This was his response every time a larger child bullied him.

I am not sure how much damage the diminutive Jones boy did, but the bullies knew they would cop at least a few swings and the tirade would take up a lot of time and energy so they never bullied him again! I have always hated bullies, whether schoolyard, politics or in management. I have never forgot Jones response as a metaphor for how to engage with bullies. Fighting back has cost me jobs and a career in politics, but I have never forgot the lesson I was taught by an 11-year-old snowy haired boy by the name of Jones. It really is better to die on your feet than live on your knees.

Everyone Comes from Somewhere

The Far North Queensland we had come to know and love was unique and special, but very young. Edmonton had for thousands of years been home of the Yidinji people. To the north were the Irrijanji and to the south east the Koonganji. Their traditional ways and movements stretched back longer than anyone knew. But what kind of people moved here and why? Just as today, drivers were escaping hardship, accessing opportunity and in some cases, a simple love of adventure. Marion married Tom when she was eighteen and he was twenty. The marriage joined two pioneering families, the Wienerts and the Pynes.

The Pyne name has been in Cairns since the early days of settlement. My great-great grandfather, James Pyne, skippered the schooner “The Freddy” which plied the east coast waters, taking supplies to the fledgling settlements at Port Douglas and later Cairns. A true pioneer of the far north, he went on to become one of the founding fathers of Cairns, at a time when it was being carved out of mosquito-infested mangrove swamps. James Pyne, a pioneer merchant, trader, entrepreneur, landowner, industrialist and philanthropic businessman was an original member of the Cairns Divisional Board (the local Council of the day).

His great grandson, my father Tom was born in 1935 in one of Australia’s most beautiful and wettest of areas, the sugar town of Babinda. Nestled at the base of Mt Bartle Frere, Qld’s highest peak, Babinda is 40 minutes south of Gordonvale. Dad went to Bellenden Ker State School about nine miles north of Babinda and his father Jack owned a small cane farm at a place called Deeral. Dad’s parents John (Jack) and Katherine Pyne were salt of the earth people and taught young Tom that nothing comes from nothing. Their children were young Jack, the oldest of the brood, followed by Ethel, Frank and Grace, with Tom the youngest.

After the War, Frank was a member of the allied armed forces occupying Japan. While in Japan he met and fell in love with a woman named Cheako. Such an occurrence was not unknown. Indeed, with that many young men wedding, that the term ‘Japanese War Bride’ was born. However back in Australia anti-Japanese sentiment remained strong. The hostility was real and raw, and in some ways understandable following the inhumane treatment of Australian troops during the war. So, when Kate Pyne went to the train station to welcome her son home and embraced his new Japanese wife, there is every reason to believe her heart was breaking. However, that hug would not have been just for the benefit of Frank or other family members but to send a message to any other onlookers this woman is “one of us” and that love conquers all.

On my mother’s matriarchal line, Johan Weinert was born on a boat making its way to Australia from Germany in 1880. After arriving in Australia, his family settled in Cooktown and in true Aussie fashion, Johan became Jack. He married another European arrival to the Far North, Johannah Thygesen from Denmark. One of their children was my grandmother, Christina Margaret May Weinert. Born in Gordonvale on May Day (1st May) 1915, Christina Margaret May Weinert was from that day forth, known simply as May.

May married a Scottish man named McKinnon at the tender age of 18. McKinnon was a wanderer and abandoned her with child, disappearing to parts unknown. Young May soon met my grandfather Robert (Bob) O’Connell and they fell in love, despite both already being married to another. Bob was born into a catholic family living in Kenny Street in 1912. Bob and May met during the depression and had not been together long when war with the Japanese broke out. Resigning from his exempted job as a bridge builder, Bob joined the army, only to be captured in the fall of Singapore, spending the remainder of the war in Changi prisoner of war camp.

Robert O’Connell’s generation could well be described as ‘the great generation’ for their contribution to our nation. They gave their all at time of war, when for those in Far North Queensland, the threat of invasion was very real and the enemy was nervously close. Like the other survivors from Changi, Bob returned home from the war starved and emaciated. You could count every rib on him. Bob also carried a scar halfway between his shoulder and neck, the result of not a not displaying the required respect to a Japanese soldier. The poor state of these men improved over time. While the physical scars disappeared, far more problematic were the emotional scars. Back then the term ‘Post Stress Traumatic Disorder’ had not yet been invented and even if it had I doubt the men of that era would have readily embraced it. The only thing that passed as medication for Robert O’Connell during weekends and post retirement were his two daily trips to the Hambledon Hotel, his morning session and his afternoon session.

At the Hambo Bob O’Connell gave new meaning to the term regular. You could set your watch by his arrival and departure during the morning and afternoon sessions. Fortunately, except for a few metres, it was a straight line from his home at 90 Mount Peter Road to the Hambo. Drink driving was not the concern back then it became later and some said his old Toyota Corolla new the journey that well that it would have driven itself to the pub and back regardless of whether he was at the wheel or not.

Bob and May were never be able to wed as Bob had left his Catholic wife who would never divorce and May would never hear from or be able to find McKinnon to divorce him. So my mum was born out of wedlock in 1937. However, Marion was a caring and giving woman, so in its wisdom the world withheld the adjective bastard, only to apply it metaphorically to me as I took on the world on my own terms, using a approach learnt from observing a small white haired boy at Hambledon State School.

Also Thanks To My Existence Supporters Who Upvote Me And Support Me @simonhbosch @normbond @nagavolu @jenpyne @oneazania

And I Encourage You To Support Them!