The EPA, Monsanto, and the Cover Up at Times Beach

When I was a little girl, I remember driving on I-44 with my mom past the desolate remains of what used to be Times Beach, Missouri. The streets sat empty, save for the dark, windowless husks of decaying, abandoned houses. She would always tell me about how that was where everyone had to be evacuated because toxic waste contamination had poisoned the place. Even though I was barely old enough to understand what that meant, every time we’d drive by on our way out into St. Louis County to visit family, I’d get that tingly feeling in the pit of my stomach knowing we were going to pass it. In my young mind, I thought if any place was truly haunted, it had to be Times Beach.

The Official Story

The official story goes like this. About seventeen miles southwest of St. Louis sat Times Beach, a small community which began as a summer resort back in the 1920s. By the 1970s, it had become a low-income housing community with a population of 1,240 people that could not afford to pave its dusty roads. In an effort to control the dust, the city hired waste oil hauler Russell Bliss to spray them down, which he did multiple times between 1972 and 1976. The government would later claim Bliss obtained the dioxin-laced waste he dumped on Times Beach in 1971 from a Verona, Missouri plant where chemical byproducts including the toxic chemical byproduct of Agent Orange was manufactured… waste Bliss surreptitiously mixed in with the oils he sprayed on Times Beach roads as his means of “disposal”. This plant would later show concentrations of dangerous dioxin at up to 2,000 times higher than that found in Agent Orange itself. By 1985, Times Beach was disincorporated, evacuated and quarantined, save for one elderly couple who refused to leave. The town wasn’t demolished until 1992. More than 265,000 tons of tainted soils were incinerated at the site beginning in 1996, and by 1997 all was declared well and the state opened up a Route 66-themed park on the former site with a ribbon cutting ceremony on September 11, 1999.

The whole incident went down as the largest civilian dioxin exposure in U.S. history. But between the time the roads were sprayed with multiple dangerous, deadly chemicals and the time the EPA declared “one of the greatest triumphs over environmental disaster” had come to an end in 1997, a lot of conflicting information and unresolved details still leave a lot of big questions about Times Beach.

A Few More Details…

Bliss came under scrutiny after he sprayed his oil mixtures at several horse farms including a May 1971 incident at Shenandoah Stable where animals began dropping dead after Bliss sprayed 2,000 gallons of a thick pungent waste oil with a foul burning odor on Judy Piatt’s indoor arena. In the weeks that followed, birds began dropping dead, dogs and cats were falling ill, and horses who came near the place were getting sores and losing their hair. Judy and her kids got headaches, nosebleeds, abdominal pain and diarrhea. After just a few months, over 60 horses died. When Judy called him on it, Bliss claimed he had sprayed nothing but old motor oil.

NEPACCO paid IPC $3,000 per load to remove the toxic waste, and IPC in turn pawned the stuff off on Bliss to do away with for a mere $150 a load. No one up or down the chain asked any questions about what the stuff was, especially not Bliss before he hosed down farms and city blocks where families lived and children played. Not trusting Bliss, Piatt began following him and his drivers on their daily routes. She compiled a list of where they collected their waste, including photographic evidence, for an upcoming civil suit. After more horses dropped dead at the other farms Bliss sprayed, the CDC got involved in August 1971, collecting soil and human and animal blood samples. They found deadly PCBs right away, but it wasn’t until July 1974 they detected up to 30 ppm of dioxin from the Shenandoah Stable samples.

Meanwhile Bliss had already been spraying the over 20 miles of roads at Times Beach intermittently for three years. Even though Bliss was under investigation for improperly disposing of hazardous, toxic waste and the government apparently knew where he was spraying his waste oil, no one informed the people of Times Beach.

Skip ahead to 1979 when a NEPACCO employee finally blew the whistle on the company’s shoddy dioxin-disposal practices, including the burial of 90 corroded, leaky drums of toxic waste on a nearby farm for a measly $150. That’s when the EPA finally got involved. By mid-1982, the agency was making rounds on the farms and reportedly visited Times Beach as well, but still no one informed the town itself what had happened. That fall, the Environmental Defense Fund leaked an internal EPA document detailing that the agency had previously known of 14 confirmed and 41 possibly contaminated sites in Missouri, with Times Beach at the top of the list.

According to the town’s last mayor Marilyn Leistner, Times Beach wasn’t told about its potential poisoning until November 1982, when a reporter called and informed the city clerk that Bliss might have doused the place with toxic dioxin.

A call from the EPA soon followed, officially informing Times Beach that it was a suspected dioxin dump site but that it might be nine months before any soil testing would be done. The town devolved into chaos at the news.

Many residents immediately remembered the city’s streets had turned a particularly alarming shade of purple after Bliss sprayed there, and animals including birds and dogs had also died. One resident even collected some of the dead birds and contacted the St. Louis Health Department, who instructed him to freeze the birds for them, but no one ever came to retrieve and test them. The roads commissioner recalled that the city had finally ordered Bliss to stop oiling Times Beach, but just a few days later found one of his drivers had dumped an entire tank of waste into an undeveloped part of the city – the part that would soon become the town’s baseball field.

The townspeople demanded answers and threatened the EPA that if the agency didn’t come test the soil right away, they would pay for their own independent samples to be taken and make the results public. That made the EPA speed up their schedule. The EPA collected soil samples on December 3, 1982. Unfortunately for Times Beach, that wouldn’t be the only tragedy. Due to massive rains, just two days later on December 5th, the Meramec River flooded, putting over 95% of Times Beach under ten feet or more of water. The town was evacuated.

The EPA wouldn’t come back with its soil sample results until December 23rd. Not only was dioxin found at levels 100 times higher than the one part per billion generally considered to be hazardous to human health, but nine other toxic priority pollutants were found in the soils there, including PCBs in the park, a finding also confirmed by the town’s independent soil tests. Two days before Christmas, the EPA told the residents, “If you are in town, it is advisable for you to leave and if you are out of town, do not go back.”

Later it came out that while the CDC had discovered dioxin in dangerously high concentrations at the Verona plant, interestingly no PCBs were ever found at that plant, and, as it turns out, IPC and NEPACCO weren’t Bliss’ only clients.

He also had contracts with major corporations… including Monsanto.

Monsanto denied this outright, but multiple Bliss drivers testified over the years that they had picked up waste from Monsanto on many occasions, including Bliss himself who told a Missouri assistant attorney general that Monsanto was his biggest client. Missouri Dept. of Natural Resources had not only received two contracts between Bliss and Monsanto dated 1975 and 1976, but at a 1977 hearing, evidence was presented that a Bliss driver had dumped a toxic chemical exclusive to Monsanto at a site in Jefferson County which Bliss subsequently testified came from a “Monsanto research lab” (source). Judy Piatt of Shenandoah Stable further claimed she too had gathered evidence Bliss drivers had picked up waste from Monsanto. She was awarded multiple lawsuits, including an IPC payout of $1 million to each of her daughters in 1983.

In a lovely little trick of semantics, when Riverfront Times contacted Monsanto about these allegations, company spokeswoman Diane Herndon responded with a prepared statement that, “No information exists that any dioxin material was hauled by Bliss for Monsanto and so no material from Monsanto would have been sprayed on roads.”

One does not automatically equal the other.

Once the EPA and DNR had zeroed in on the Verona plant as the sole source of the contamination, they apparently never looked further into any other companies contracted with Bliss, including Monsanto. Activist Steve Taylor of the Times Beach Action Group told reporters leads weren’t followed up on if they didn’t fit into the theory of where the waste came from, despite the fact that no PCBs were ever found at the Verona plant.

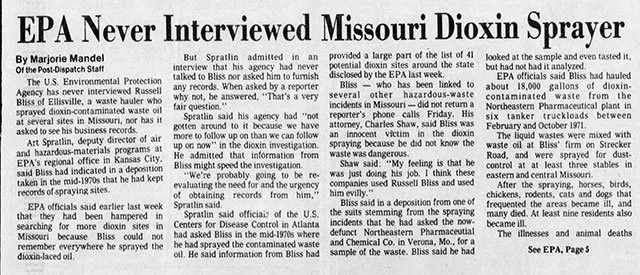

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 1, 1982

Dioxin is a probable carcinogen that’s been linked to skin diseases, immune disorders, birth defects, and worse.

[caption id="attachment_14526" align="alignleft" width="435"] Times Beach Final Mayor Marilyn Leistner standing before a house showing the how high the flood waters rose in December 1982.[/caption]

Times Beach Final Mayor Marilyn Leistner standing before a house showing the how high the flood waters rose in December 1982.[/caption]

Then the board found out the federal government likely knew about the contamination at Times Beach going all the way back to 1972, but did nothing to alert Times Beach residents.

It looked like a cover up. The situation went all the way to the federal level, and in January 1983 President Reagan announced a Times Beach Dioxin Task Force. A month later the EPA announced a federal buyout of the town for $33 million. It was the first time the government had ever done so under these circumstances in American history.

The official quarantine began in 1985, but the town would not be demolished for another seven years. Though thousands of lawsuits were subsequently filed against Bliss, IPC, and NEPACCO, Bliss was never convicted of any crime for what he did. For his part, Bliss claimed he was just a patsy and that he was never informed the waste he received could be hazardous, a defense that makes little sense in hindsight considering who his clients were.

As the cleanup finally began, the controversy only grew. An incinerator was placed on the site in the mid-90s by Syntex, the company that bought out NEPACCO, where over 265,000 tons of dioxin-contaminated soil from more than two dozen sites around Missouri would be incinerated on the Times Beach site. In fall 1997, the Justice Department quietly initiated a criminal inquiry into the disputed stack emissions tests for the Times Beach dioxin incinerator, after it was revealed two separate EPA and DNR reviews of said data revealed serious lapses in scientific protocol which cast doubt on whether the incinerator was functioning properly and legally protecting human health (a pretty big deal, considering that one way dioxin is spread to begin with happens to be incineration).

Times Beach incinerator

Despite the fact that Judy Piatt, Mayor Marilyn Leistner and a civil attorney all recalled that PCBs had been found in the Times Beach park, the EPA claimed in 1991 the PCBs – a highly toxic and non-biodegradable environmental pollutant – had somehow magically vanished… end of story.

It should be noted that from the 1930s until 1977, Monsanto was the largest PCB producer in the United States. An Agricultural Chemicals newsletter dated March 16, 1972 notes that at that time Monsanto was the only domestic producer of PCBs and, despite disturbing scientific evidence of the dangers, Monsanto “continues to stand firm behind its contention that there is no scientific data that indicate polychlorinated biphenyls may cause birth defects.”

A lawsuit later resulted in the release of a 1975 letter from Monsanto which instructed Westinghouse to downplay the potential harm of PCBs to the company’s employees, but admitted that polychlorinated biphenyls “can have permanent effects on the human body”.

It just came out in August 2017 that Monsanto was fully aware of how dangerous PCBs were but continued to produce the toxic chemicals for another eight years anyway, through 1977. They were banned entirely by 1979.

Back at Times Beach, the EPA quietly hauled over 4,400 tons of “special” waste off-site to a landfill that had been cited by DNR in the past for potentially allowing waste to seep into the ground and contaminate groundwater. Not only that, but another EPA document dated 1982 proved that that specific landfill had also likely been sprayed by Bliss a decade earlier. (See how that works?)

When questioned about it by reporters, everyone involved in the special dump cited confidentiality agreements with the EPA. No one would talk.

Worse, Richard J. Daykin, an employee of the engineering firm connected to this special landfill had befriended activist Taylor who convinced him to testify before an environmental attorney preparing a federal suit to halt the potentially dangerous incinerator operations at Times Beach because the guy had not only witnessed safety violations at the incinerator site but irregularities with the Times Beach soil sampling. Unfortunately he died in a one-car accident before he could have his turn on the witness stand.

Something was definitely being covered up.

Riverfront Times also discovered that in 1982, the DOJ – then acting on behalf of the EPA and the White House – withheld documents on the Times Beach cleanup including handwritten notes of EPA attorney James Kohanek pertaining to the Missouri dioxin sites and their proposed cleanup. They cited executive privilege and refused to turn the information over to Congress for reasons that remain secret to this day.

Activist Steve Taylor summed it up best when he said,

“We believe this is more of a toxic-waste shell game than a clean up. We feel there’s a lot of secrets. That this whole incineration project was about preserving secrets and protecting commercial interests more than protecting public health.”

Just a few weeks after the incinerator was shut off at Times Beach for the final time, the EPA announced it had found another dioxin-laced site in Ellisville. In august 1997, Taylor was hit with a legal action from the agency using a provision in the Superfund law that is supposed to be reserved for corporate polluters, giving Taylor one week to turn over any information he and his group may have on the disposal of any hazardous wastes generated by Monsanto or face a fine of $25,000 a day until he did. The order came two weeks after Taylor formerly asked the St. Louis County Council to form a task force to independently investigate other contaminated sites overlooked by the EPA and DNR.

Today a giant vented grassy mound of leftover debris from the town of Times Beach sits in the new Route 66 park the state turned the site into (above), a park as creepy and desolate as the abandoned husk of a town I remember driving by as a child.

The old roadhouse is the only original Times Beach building left standing. Used by the EPA as its headquarters during the cleanup, it has now been turned into a Route 66 museum and knick knack gift shop. Only one tiny corner of the place has any information about the tragedy that befell Times Beach for years, and even that is set up to spin the entire event as one big triumph for the EPA.

It’s pretty insulting.

In 2012, the EPA retested soil samples from the Route 66 State Park and in November declared, “Soil samples from Route 66 State Park show no significant health risks for park visitors or workers.” Notice they did not say the place was found clean and there were no health risks, just that it posed no significant health risks. The page for the 2012 Route 66 test results has apparently been taken down from the EPA’s website.

Meanwhile, the long-term health effects on the residents of Times Beach are still unknown.

Despite the fact that everything was long ago demolished, buried, and burned, after looking at all the evidence of the Times Beach dioxin scare, it would seem that someone was covering up a much more dangerous chemical… tied to a much larger, more powerful company.

(Some details above were taken from Mayor Marilyn Leistner’s Times Beach story as presented at the 3rd Annual Hazardous Materials Management Conference in Philadelphia in June 1985. You can read it here.)