This post will discuss South Africa's educational system and how it impacts unemployment, inequality and poverty. The government's challenges facing the educational system in South Africa will be analysed and contrasted with other developing countries. The importance of improving education is in its most basic state, to increase human capital and have a more productive population. South Africa's education situation has gone under much reform since the end of apartheid as the system was catered towards a small white population and not the overall population. This still has its roots in the education system as inequality is still high. Recommendations and various solutions will be mentioned in regards to government policy.

According to the South African budget review for 2016 (National Treasury, 2016), out of South Africa's R1.46 trillion rand spent on expenditure R297.5 billion rand of total expenditure is spent on education, roughly 20% of total expenditure. This indicates a lack of efficiency in the education system and allocation of resources. South Africa has a large, young and unproductive population with high unemployment and poverty rates. However, the investment in education is still a good indication that the government is targeting inequality, poverty and unemployment (Unesco, 2016).

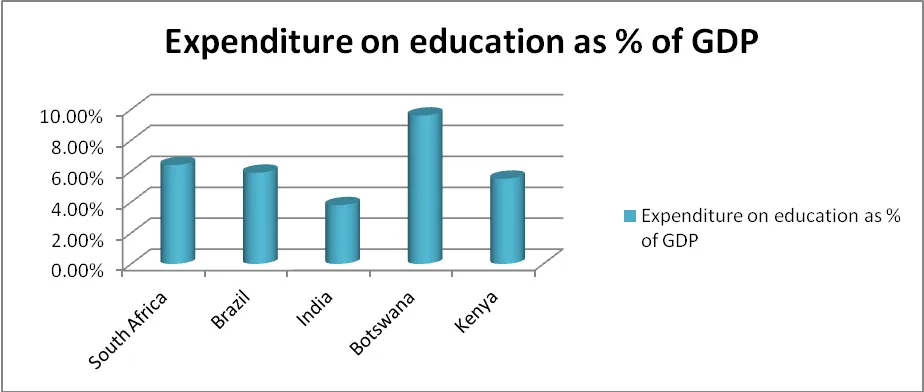

We can see below, that from an analysis done by the World Bank that South Africa's spending on education as a percentage of GDP in 2012 was 6.4% (we use this indicator instead of a percentage of total expenditure as not all countries are equal in terms of expenditure available). During the same period, Brazil and India's spending on education were 5.9% and 3.8% respectively. Compared to other African countries such as Botswana and Kenya their expenditure on education was 9.6% and 5.5% respectively; the African countries chosen are all developing, upper middle income and middle-income countries (Databank, 2016). South Africa is the second highest country in terms of expenditure and one of the worst performing, reasons for this will be discussed.

When looking at these 5 countries we see that South Africa, Brazil, Botswana and Kenya all invest a large part of their GDP into education indicating that they have a higher capacity to raise revenues for public spending. Botswana invests more of their overall GDP into education; however, we can also argue that South Africa has a higher GDP requiring less investment. India is the country with least investment in education; like South Africa, India also has a large poverty stricken population where many young people miss out on education simply because they cannot afford it. (Murtin, 2013).

In order to put expenditure into perspective, we use SACMEQS (Stat Planet, 2016) data for pupil achievement in math and reading skills for grade 6 (African countries only). As we can see out of all the countries South Africa performs the worst with the second most investment. Kenya has the least investment but the highest scores out of the countries. This indicates that South Africa is underperforming when compared to less wealthy countries.

A report done by Nicholas Spaull (Centre for development & enterprise, 2013) highlights South Africa's deficiencies when it comes to education at all levels, claiming that most South African children are performing below what the syllabus requires, often failing to acquire functional numeracy and literacy skills. The report also states that South Africa has some of the least-knowledgeable primary school mathematics teachers in sub-Saharan Africa. Many maths teachers, especially those that assist poor and rural communities, have below-basic levels of expertise.

| Country | Reading |

|---|---|

| South Africa | 493.3 |

| Botswana | 521.1 |

| Kenya | 546.5 |

| Mozambique | 516.1 |

| Country | Mathematics |

|---|---|

| South Africa | 486.3 |

| Botswana | 512.9 |

| Kenya | 563.1 |

| Mozambique | 529.7 |

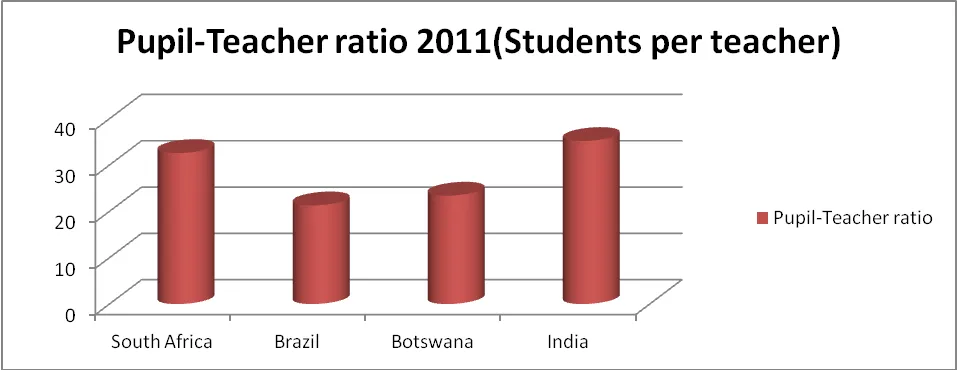

When comparing South Africa to other developing countries we can use the teacher to pupil ratio indicator to determine whether funds are being allocated efficiently and the quality of schooling each individual receives. According to the chart below with statistics from the World Bank for 2011(Databank, 2016); South Africa's pupil-teacher ratio in primary education was 32.6 pupils per teacher whereas Brazil was 21.3 pupils per teacher and Botswana 23.4, despite Brazil spending less of its available expenditure on education. South Africa is more comparable to India in regards to this ratio as both are similar. This is a bad thing for South Africa as its population is less than a quarter of India's and is classified as an upper middle-income country whereas India is categorised as a lower middle-income country with half the amount of GDP percentage spent on education as South Africa.

This ratio highlights one of South Africa's key problems, which is an inefficient allocation of resources. This can also be applied to the infrastructure of South African schools in which resources are not used wisely. According to the Provincial Budget and Expenditure review (2015);" Numerous learners attend classes in unsuitable buildings. In addition, there are still too many schools without clean running water, proper sanitation facilities or electricity". This can dissuade learners and teachers alike from wanting to attend and participate.

It is also apparent that spending more resources is not the solution to resolve these problems since existing resources are not yet being handled effectively. Resources are mediated by provinces and schools – both of which vary widely in their ability to manage financial and human resources. There is a need to ensure better accountability between the department, the schools and the parents. ("South African education: unequal, inefficient and underperforming", 2016)

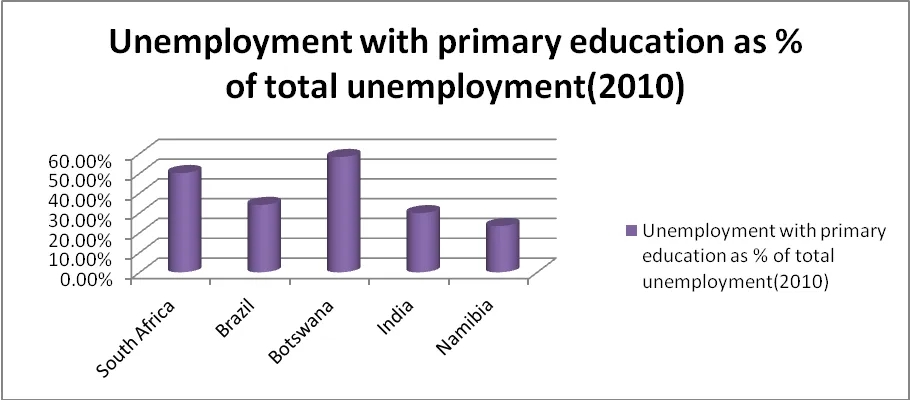

We use Unemployment with primary education (as % of total unemployment) to determine how South Africa's education performance affects the economy compared with other developing countries. When looking at other developing countries compared to South Africa we can see that their levels of Unemployment with primary education is low (the exception being Botswana). This expresses that a large portion of South Africa's population is lacking higher education and relates to the underperformance of South Africa's education system. The lack of higher education is due to out of school factors such as poverty, which negatively impacts the attitude of parents and society towards education (Branson, Garlick, Lam, & Leibbrandt, 2012).

According to Todaro and Smith (2014), a high number of the unemployed citizens with low education levels may suggest that their education level be increased or more low-skill occupations are created. The problem lies in that South Africa's population is not productive, productivity can be defined in this scenario to be the inherent skills an individual brings to the table. This statistic is high simply because there is an abundance of unskilled workers, therefore, there is a large supply of unproductive workers with not enough demand for them causing wages and job opportunities for those with little to no skills to be very low, especially within the informal sector.

An extensive topic when discussing education in South Africa is inequality within the system. Analysis of South African educational system shows that there are in effect discrepancies between schools depending on language, school location, province and wealth. A study done by N. Spaull (Centre for development & enterprise, 2013) showed that the average grade nine student in KwaZulu-Natal was 2.5 years worth of learning behind the average grade nine student in the Western Cape for science, and that the average grade nine student in the Eastern Cape is 1.8 years’ worth of learning behind the average student in Gauteng.

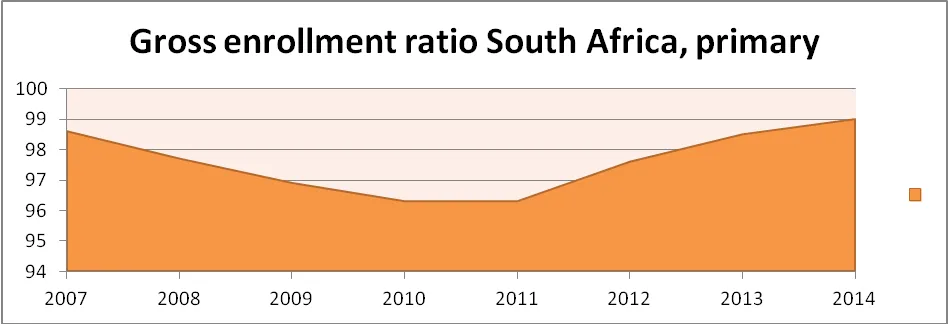

The inequality problem within South Africa is one of achievement and not attainment; primary school enrolments are not an important concern (World Bank Development Report, 2007). Factors such as pupil-teacher ratios and school infrastructure have a more significant impact on years of schooling completed, the chances of employment and educational returns to private and social entities. Inferior school quality results in students completing fewer years of schooling, having less opportunity of employment when entering the labour market, and experiencing lower returns to education when employed, compared to students who received higher quality schooling (Branson, Garlick, Lam, & Leibbrandt, 2012).

If South Africa's investment in education is successful there will be great gains, many of South Africa's core problems can be solved. Education will help reduce poverty in the country by increasing income and employment rates. An increase in health would occur due to the increase in income and therefore cause an increase in productivity. Having a more productive society would increases investments and boosts economic growth (Todaro & Smith, 2014).

In a paper done by Centre and Development Enterprise founder Ann Bernstein (Centre for Development and Enterprise, 2011) she concluded that South Africa is in need of skilled teachers and that there is a scarcity of teachers proficient in maths and science. The National Planning Commission (National Planning Commission, 2010) recently identified poor education and youth unemployment as the country’s two key challenges and identified the dedication of teachers as a key cause of poor student performance.

The NPC believes South Africa is receiving poor value for money from its teachers: "Literacy and numeracy test scores are low by African and global standards, despite the fact that government spends around 6 percent of GDP on education and South Africa’s teachers are among the highest paid in the world (in purchasing power parity terms)".

For South Africa to improve its teaching crisis, teaching needs to be made a more attractive profession. This is especially the case when it comes to ensuring that South Africa retains and attracts competent teachers in mathematics and science as well as other subjects in short supply. The government needs to provide more bursaries for teacher training in order to increase the amount of proficient and potential successful teachers. A final solution for improving the teacher situation is offering incentives to teachers who reach performance targets, this policy has been successfully implemented by Brazil, India, and the USA. (Murtin, 2013)

N. Spaull (Centre for development & enterprise, 2013) argues that every school needs to be brought up to a minimum standard, in which learners will all be offered the same level of education. This plan is already in effect as of November 2013 when Angie Motshekga, published legally binding Norms and Standards for School Infrastructure. It states that every school must have water, electricity, internet, working toilets, safe classrooms with a maximum of 40 learners, security, and thereafter libraries, laboratories and sports facilities.

In order for South Africa to improve its allocation of resources, there needs to be a delegation of responsibility, according to (Branson, Garlick, Lam, & Leibbrandt, 2012), the government needs to provide a clear articulation of who is responsible for ensuring student learning with clear consequences for non-performance. This can be done by implementing systematic plans to increase accountability.

Various countries have tried different approaches to improving school quality, and thus educational achievement which is what South Africa lacks. These approaches include policies constructed to increase school liability to the community, such as increasing the information available to school communities and encouraging parent and youth management, which can improve teacher performance (National Treasury, 2015).

We can conclude that South Africa's educational system is performing below expectations considering the investment in education when compared with other developing countries. It was found that inequality and teacher quality are determining factors in South Africa's education standard. Infrastructure in South Africa was determined to be insufficient and not conducive to a productive learning environment. The government is recommended to implement policies that target teacher quality and efficient allocation of resources as the amount invested into education is currently not the issue. Overall the goal of increasing education standards is to improve human capital and provide solutions to socio-economic problems.

References

Branson, N., Garlick, J., Lam, D., & Leibbrandt, M. (2012). Education and Inequality: The South African Case. South Africa Labour And Development Research Unit, 75. Retrieved from http://isites.harvard.edu/fs/docs/icb.topic1222150.files/Session%2016/2012_75_SA_Education_Inequality_MurrayMilbrandt.pdf

Centre for development & enterprise,. (2013). South Africa's Education Crisis: The quality of education in South Africa 1994-2011. Johannesburg. Retrieved from http://www.section27.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Spaull-2013-CDE-report-South-Africas-Education-Crisis.pdf

Centre for Development and Enterprise,. (2011). The quantity and quality of South Africa's teachers. Pretoria. Retrieved from http://cdn.mg.co.za/uploads/2011/09/21/value-in-the-classroom-full-report.pdf

Murtin, F. (2013). Improving Education Quality in South Africa. OECD Economics Department Working Papers. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k452klfn9ls-en

National Planning Commision,. (2010). Diagnostic Overview. Pretoria.

National Treasury,. (2015). Provincial Budgets and Expenditure review: 2010/11-2016/17 (pp. 33-39). Johannesburg.

National Treasury,. (2016). Budget Review (p. iii-v). Pretoria.

South African education: unequal, inefficient and underperforming. (2016). Unisa Online - College of Education. Retrieved 4 May 2016, from http://www.unisa.ac.za/cedu/news/index.php/2012/07/cedu-microwave-presentation-south-african-education-unequal-inefficient-and-underperforming/

StatPlanet - Interactive Maps of World Development. (2016). Sacmeq.org. Retrieved 4 May 2016, from http://www.sacmeq.org/interactive-maps/statplanet/StatPlanet.html

The World Bank DataBank | Explore . Create . Share. (2016). Databank.worldbank.org. Retrieved 4 May 2016, from http://databank.worldbank.org/

Todaro, M. & Smith, S. (2014). Economic Development (12th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

World Development Report(2007). Development and the Next Generation, World Bank Publications, 2 – 21.

UNESCO. (2016). UNESCO. Retrieved 4 May 2016, from http://en.unesco.org/