I have been running Marathons for a quarter of a century. Over the course of those twenty-five years, I have run twenty-three Marathons. And each of them has been fueled by the traditional diet of the endurance athlete:

- High in Carbohydrates

- Low in Fat

- Moderate Protein

This diet has served me well over the years. I ran every one of those Marathons in under three hours, including a PB of 2:33:25 in Paris 2013, when I was 49 years old:

| Marathon | Year | City | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1993 | Dublin | 2:55:33 |

| 2 | 1994 | Dublin | 2:39:03 |

| 3 | 1998 | Dublin | 2:48:08 |

| 4 | 1999 | Dublin | 2:37:43 |

| 5 | 2000 | Dublin | 2:50:19 |

| 6 | 2001 | Dublin | 2:50:22 |

| 7 | 2002 | Dublin | 2:49:40 |

| 8 | 2006 | Dublin | 2:57:20 (Chip: 2:54:39) |

| 9 | 2007 | Dublin | 2:53:29 |

| 10 | 2008 | Dublin | 2:46:13 |

| 11 | 2009 | Dublin | 2:41:25 |

| 12 | 2010 | Belfast | 2:40:43 |

| 13 | 2010 | Dublin | 2:36:23 |

| 14 | 2011 | Belfast | 2:40:51 |

| 15 | 2011 | Dublin | 2:38:41 |

| 16 | 2012 | Edinburgh | 2:38:02 |

| 17 | 2012 | Dublin | 2:35:23 |

| 18 | 2013 | Paris | 2:33:25 - PB |

| 19 | 2013 | Dublin | 2:38:42 |

| 20 | 2014 | Paris | 2:35:28 |

| 21 | 2015 | Budapest | 2:41:05 |

| 22 | 2017 | Cork | 2:57:50 |

| 23 | 2017 | Pisa | 2:44:55 |

But after twenty-five years, my routine is becoming a little stale. I think it’s time for a change. I have decided to shake things up and invigorate my approach to Marathon running: I’m going Keto!

The Ketogenic Diet

The Ketogenic Diet could hardly be any more different than the traditional diet favoured by endurance athletes:

- High Fat

- Low Carb

- Moderate Protein

I first heard of this diet in October 2018, when a video by Dr Annette Bosworth popped up in my recommendation feed on YouTube. The title of the video was Autophagy and Fasting: The Mystery Explained. Intrigued, I decided to take a look—and that was how I was first introduced to Dr Boz and the world of ketosis.

This short video included some technical terms that were new to me: autophagy, apoptosis, and ketosis. It was the latter that really caught my attention. In the course of the video, Dr Boz contrasts someone following a traditional high-carb diet with someone on a low-carb diet:

Now, compare that to someone who’s in ketosis, who’s using fat as their fuel most of the time. They have less than 20 [grams of] carbohydrates that come in a day ...

It was quite a shock to hear a medical doctor promoting a high-fat diet, given all that we have been told over the past fifty years about fat and its alleged links to chronic obesity and heart disease. It was also a bit confusing. In the video, Dr Boz does not say 20 grams of carbohydrates. What she actually says is 20 carbohydrates. To a seasoned practitioner of the Ketogenic Diet, it is obvious that she means 20 grams. Even in countries like the US and the UK, where the Imperial system of units still rules, practitioners of the Ketogenic Diet measure their carbs in grams. But to a complete novice, who has never even heard of this diet, it is not obvious at all: does she mean 20 g, or 20 oz, or 20 servings? Is it like the recommended 5 a day for fruits and vegetables?

After watching the video through to the end, I began to browse through the comments. I kept coming across statements like the following:

- I’ve been keto for about a year now

- I lost 100 lbs on keto and intermittent fasting

- I started keto and fasting 5 months ago and I already lost 100 pounds, love keto and love fasting.

This keto was clearly a big thing in America, but it hadn’t reached Ireland yet. I had never even heard of intermittent fasting.

Over the course of the following months I watched many more videos on YouTube devoted to ketosis, the Ketogenic Diet and intermittent fasting. Among the channels I found most helpful I might mention the following, most of which also have lots of ketogenic recipes:

- [Dr. Boz Annette Bosworth, MD

- Dr. Eric Berg DC

- Thomas DeLauer

- Keto Connect

- Dr. Nick Zyrowski

- KenDBerryMD

- Ketobetic Aline

- Keto Christina

- Tara’s Keto Kitchen

- Sonal’s Food

- TPH Keto Desserts

- Dr. Nicholas Sudano D.C.

- Papa G’s Low Carb Recipes

- Lazy Keto

- stephanie Keto person

- The Keto Chef

Naturally, I also looked at the literature and did some research into the science of ketosis. Eventually I purchased the Kindle version of The Ketogenic Bible: The Authoritative Guide to Ketosis by Dr Jacob Wilson and Dr Ryan P Lowery. The authors are not only enthusiastic supporters of the Ketogenic Diet, but also pioneers in the field of clinical research into ketosis and the Ketogenic Diet. They are not, however, medical doctors: their area of expertise is in sports medicine.

Ketosis

So what is ketosis?

Ketosis is a metabolic state in which some of the body’s energy supply comes from ketone bodies in the blood, in contrast to a state of glycolysis in which blood glucose provides energy. Generally, ketosis occurs when the body is metabolizing fat at a high rate and converting fatty acids into ketones. (Wikipedia)

On the traditional Western diet or the endurance athlete’s diet, both of which are high in carbohydrates, glucose (a carbohydrate) is your body’s principal fuel. Your liver regulates the amount of glucose in your blood, breaking down its glycogen (the human body’s stored form of glucose) and secreting it into the blood. The cells in your body can take up this blood glucose (during intense exercise muscle cells can also tap into their own private glycogen stores) and use it as an energy source. The glucose is converted into pyruvate, which is then transported into the mitochondria, where it is converted into acetyl-CoA. This then enters the Krebs Cycle (Citric Acid Cycle) in the mitochondria, where it is oxidized to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP). This energy-rich molecule is the body’s immediate source of energy—the molecular unit of currency, if you like. It provides the energy required by most of the metabolic processes in your cells: the contraction of muscle fibres, the propagation of nerve impulses along neurons, and all sorts of biochemical processes.

If, however, you starve your body of glucose by eating a diet poor in carbohydrates, you force it to find an alternative source of energy. Initially your body will break down muscle protein and convert that into glucose. This, however, is just an emergency procedure to keep the body going until carbohydrates are reintroduced into the diet.

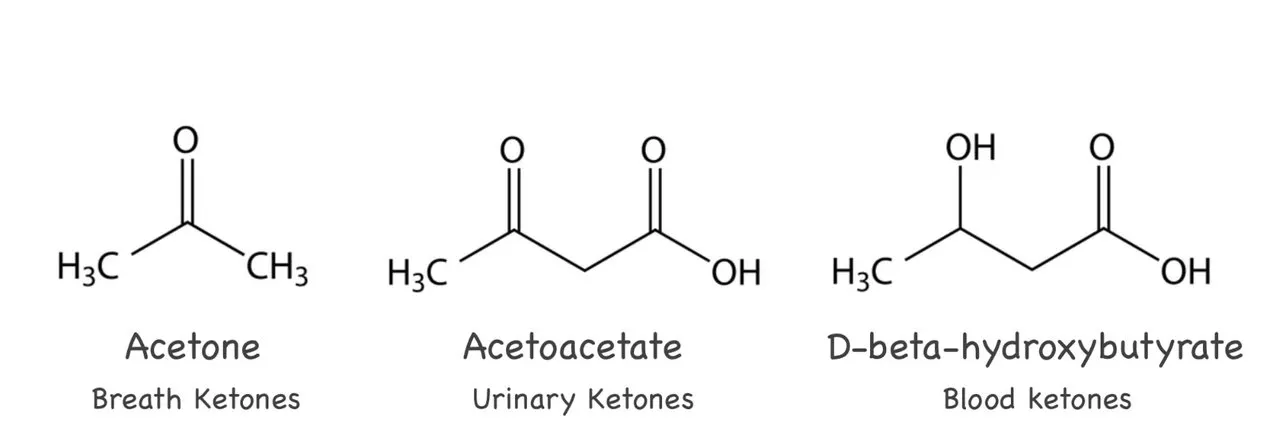

But what happens if you remain on the low-carb diet indefinitely? Eventually—typically after a few days—your body switches to fat as its principal fuel. Fatty acids are converted in the liver into ketone bodies: acetoacetate (AcAc), beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) and acetone (Ace). These are then secreted into the blood and circulated throughout the body. Your body’s cells can take up AcAc and BHB and use them as fuel in place of glucose. Inside the cells’ mitochondria, AcAc and BHB are broken down to produce acetyl-CoA, which enters the Krebs Cycle, just as in glycolysis. Ace can also be metabolized by the body to produce energy, but by a different pathway. It is not as important as the other two ketone bodies and much of it is not used by your body but is excreted in your urine and sweat and on your breath. The latter can cause acetone breath, when the distinctly fruity scent of acetone can be smelt on the breath.

The biochemistry of ketosis is complicated and is still being unravelled. For example, according to Wikipedia:

Although some biochemistry textbooks and current research publications indicate that acetone cannot be metabolized, there is evidence to the contrary, some dating back thirty years. (Wikipedia)

Or, again, many sources I consulted give the impression that ketone bodies are only produced in the liver. But this is simply not true. There is good evidence that the production of ketone bodies—ketogenesis—can also take place elsewhere in the body:

Ketone bodies are produced mainly in the mitochondria of liver cells, and synthesis can occur in response to an unavailability of blood glucose, such as during fasting. Other cells are capable of carrying out ketogenesis, but they are not as effective at doing so. Ketogenesis occurs constantly in a healthy individual. (Wikipedia)

It is, however, possible that prolonged exposure to ketosis will increase the effectiveness of ketogenesis in cells outside the liver. If muscle fibres are capable of creating ketone bodies from their own local supplies of fat, this could have far-reaching implications for athletic performance. It could mean that parallel to the glycolytic system—in which muscle fibres can utilize their own personal supplies of glycogen to fuel their activity rather than relying on the liver to provide the glucose—there is a ketotic analogue, in which the muscle fibres can produce their own ketones in situ.

[Update: Since writing this I have done further research, and it transpires that when one has become keto-adapted, the skeletal muscles are weaned off ketone bodies and come to rely mainly on free fatty acids for their energy, leaving the ketones primarily for the brain.]

The purpose of the Ketogenic Diet, therefore, is to wean your body off glucose and train it to switch permanently to fat as its primary fuel. Ketosis is the metabolic state where this is happening, and it can be brought on temporarily by fasting, engaging in prolonged exercise, undergoing starvation, or restricting the amount of carbohydrates in your diet. Obviously, you cannot fast, exercise or starve yourself indefinitely, but you can restrict the amount of carbohydrates in your diet indefinitely. If you do this, your body will adapt to this new regimen and you will become keto-adapted (fat-adapted).

It takes several weeks at least—typically three to eight—for this adaptation to occur. Some sources I consulted quoted several months, and The Ketogenic Bible cited a study which indicated that physiological changes associated with keto-adaptation in athletes were still occurring one year after the diet had been implemented.

The Health Benefits of Ketosis

Unlike many fad diets popularized by celebrities or the mainstream media, the Ketogenic Diet is supported by a plethora of scientific studies. The diet was originally developed in the 1920s as a therapeutic regimen for treating epilepsy, but despite its spectacular success, it was effectively suppressed by big-pharma in place of more expensive drug treatments. Recently, however, as more and more medical practitioners have begun to examine ways of treating diseases without medication, the Ketogenic Diet has seen a resurgence in popularity. Much of the clinical research into the diet concerns its use to treat, prevent, or even possibly cure a wide range of ailments:

- Epilepsy

- Obesity

- Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Parkinson’s Disease

- Various forms of Cancer

- Crohn’s Disease

- Huntington’s Disease

- ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder)

But in recent years the Ketogenic Diet has increasingly become a lifestyle choice for otherwise healthy people. Among the alleged health benefits of the diet for those of us fortunate not to suffer from any of the foregoing ailments are:

- Anti-Inflammation

- Low Blood Sugar

- Improved Insulin Sensitivity

- Reduced Insulin Resistance

- Reduced Hunger and Cravings

- Better Sleep Patterns

- Improved Memory and Cognitive Functions

- Reduced Body Fat

- Prophylaxis (against the ailments listed above)

- Autophagy (when the diet is combined with intermittent fasting)

Time will tell how credible this list is. My initial experience is rather a mixed bag—of which more in later articles.

Ketogenic Meals

A ketogenic meal is one whose caloric profile is designed to promote ketosis. There is currently no clinical definition of what constitutes a ketogenic caloric profile, but the following is a good guide:

| Fat | Carbohydrate | Protein |

|---|---|---|

| 60-80% | 5-10% | 15-30% |

The important point is to keep your fat calories above 60% (75% being commonly cited as an optimal target) and your carbohydrate calories below about 10%. It is also important not to allow your protein intake to exceed about 30%, as unused proteins are generally converted by the body into glucose. If you follow these guidelines consistently, your diet will promote ketosis and keto-adaptation.

To achieve this caloric profile, there are certain foods that you will generally want to avoid and certain foods that will become staples of your new diet:

| Keto Foods | Anti-Keto Foods |

|---|---|

| Fats and Oils | Sweets and Candy |

| Nut Butters | Cereals and Grains |

| Almond and Coconut Flours | Cereal Flours |

| Eggs | Fruit and Fruit Juices |

| Mayonnaise | Ketchup |

| Nuts | Legumes (except peanuts) |

| Seeds | Foods with Added Sugar |

| Meat | Pastries |

| Seafood | Cakes |

| Plant Milks | Kefir |

| Cream | Milk |

| Cheese | Yogurt |

| Americano | Cappuccino |

| Green Tea | Hot Chocolate |

| Cruciferous Vegetables | Starchy Vegetables |

| Asparagus | Crisps (Potato Chips) |

| Spinach | Chips (French Fries) |

| Herbs and Spices | Battered Food |

Strictly speaking, nothing is absolutely banned from the Ketogenic menu. Unlike a vegan who is abstaining from meat for ethical or religious reasons, someone following the Ketogenic Diet does not have to give up cereals—or even candy—completely. As long as foods rich in carbohydrates are eaten sparingly and “diluted”, as it were, by fat-rich foods, they should be all right. And there are always keto-friendly substitutes for anti-keto foods. For example, if a recipe calls for sugar, you substitute Stevia, which has no carbohydrates, no calories and is low on the glycemic index. Apples and bananas are generally avoided, but berries are an acceptable substitute when eaten in moderation. Or, again, the biscuit crumbs used for making the base of a cheesecake can be replaced with chopped nuts or almond flour.

Upon a Peak in Darien

One of the most engaging things about the Ketogenic Diet is the excitement of trying new foods and recipes. As a Marathon runner, I have spent most of my adult life avoiding things like chorizo, salami, pepperoni and mayonnaise. Now they are among the staples of my diet. It is like discovering a previously unknown and completely unexplored continent, one that is full of strange, exotic and healthy foodstuffs. The possibilities are limitless. Think Cortez on that peak in Darien. Or Homer in the Land of Chocolate.

So there’s much to learn.

References

- Jacob Wilson, Ryan P Lowery, The Ketogenic Bible: The Authoritative Guide to Ketosis, Victory Belt Publishing, Las Vegas (2017)

Image Credits

- Ketogenic Diet for Endurance Athletes: © FitFluential LLC, Fair Use

- The Ketogenic Bible: © 2017 Jacob Wilson & Ryan Lowery, Fair Use

- Ketone Bodies: © Ketogenic-Diet-Resource.com, Fair Use

- Health Benefits of Ketosis: Shutterstock, Royalty-Free Image

- The Ketogenic Pyramid: Copyright Unknown, Fair Use