Today marks 77 years since the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

We now know that the Japanese attack was hardly an unexpected event. The Roosevelt Administration had been imposing harsher and harsher trade embargoes and sanctions on the Japanese in 1940 and 1941 in response to Tokyo’s war in China that began, first, with the invasion of Manchuria in September 1931 and then with a full-blown invasion on the rest of China starting in July 1937.

FDR demanded an unconditional and full withdrawal of Japanese military forces from China, and the embargo and sanctions were meant to pressure the Japanese government to give in. The Japanese viewed this as America’s attempt to keep them a second-class world power. Especially the U.S. and Dutch oil embargoes (the Dutch controlled what today is known as Indonesia and its oil fields) left the Japanese with oil reserves only sufficient for a few months.

Thus, Japan’s choice was either to give in and be denied their chance for an “empire” in China, just as the British and French already had their empires in other parts of Asia and in Africa, or strike out and attempt to deliver such a blow to the U.S. military presence in the Pacific that Washington would have to compromise and accept Japan’s ambitions in Asia.

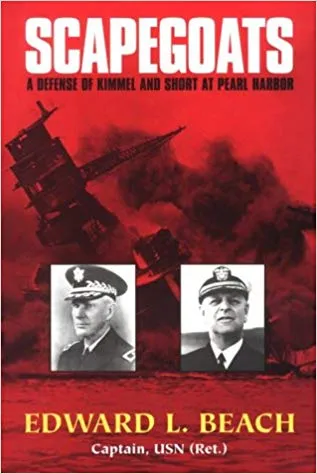

Edward L. Beach’s, “Scapegoats: A Defense of Kimmel and Short at Pearl Harbor" gives some insight into the situation and the circumstances surrounding the U.S. and it's entry to the second world war.

Beach argues that FDR and the U.S. intelligence agencies had more than enough information from their partial breaking of the Japanese codes to know that an attack on U.S. military forces in Asia and the Pacific was imminent. And that those higher up in the chain of command in Washington failed to send the appropriate information to Admiral Husband Kimmel and Lt. General Walter Short for them to successfully be on alert and prepared for the attack that began on Sunday morning at 7:55 a.m. on December 7th.

Instead, Beach documents that Kimmel and Short were made scapegoats for the disaster at Pearl Harbor that left much of the U.S. Pacific fleet sunk or severely damaged, and with over 2,400 American military personnel dead and another 2,000 wounded. At a minimum, Beach argues, FDR and those others in Washington responsible for U.S. military defences were grossly negligent in their duty.

Beach concludes that: “The national leadership which had the obligation of keeping our military commanders current with matters of their concern, utterly failed our commanders at Pearl Harbour and then proceeded blame them for their own lack of alertness . . . Giant of stature though he was, [FDR] was sometimes small enough to destroy other men to give himself protection.”

Other critics of FDR’s policies toward Japan leading up to the events on December 7, 1941, have been far more harsh with suggestions that the president wished to create the conditions for a war with Japan as a general “backdoor” to entering the Second World War on Britain’s side. Or as one of FDR’s senior advisers said at the time, the trick was to manoeuvre the Japanese into firing the first shot.