古池や蛙飛びこむ水の音

furuike ya kawazu tobikomu mizu no oto

an old pond...

a frog leaps

plop!

—Basho

(Tr. David LaSpina)

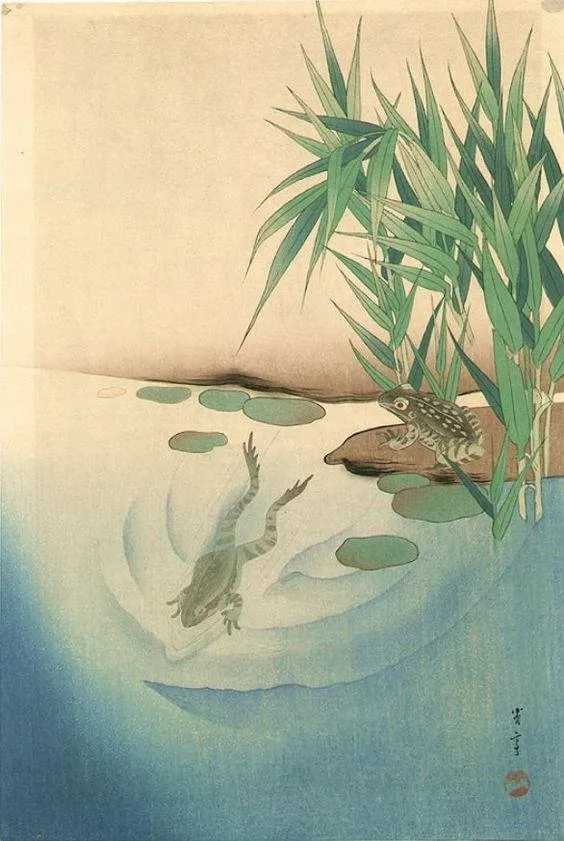

("Frogs in a Pond" by Seitei)

Commentary

Here we are—the one hundredth haiku translation post. Wow. Pretty good for a series I only began on a whim. For this milestone, I thought we would look at the single most famous haiku, both in Japan and in the world. The timing also fits, as "frog" is a spring kigo†. If you ask any Japanese person for a classic haiku, chances are good this will be the one they know‡.

This poem is thought to mark Basho's maturity as a poet. He was 37 years old and had been a published poet for 18 years, had already established a school, and had many followers. Yet almost all the haiku for which he is famous today were composed after this one. This was the start of his greatness and is why today he is considered the greatest haiku master.

The idea that haiku are a kind of zen poem has been debunked many times. Most Japanese haiku poets today, and probably all foreign ones, know little to nothing about Zen Buddhism. But in this case, Basho was a student of Zen Buddhism and this haiku is as zen as you can get. The setting is a perfect zen scene. A mossy garden, old, ancient, timeless. Then we notice the frog and hear its plop. It is very much set up like a satori moment—that is, sudden enlightenment. It is said the Buddha became enlightened upon seeing the morning star. There are many other stories of monks experiencing satori upon some sudden outside experience that freezes them, wipes away their mind, makes them one with the universe—called samadhi in Buddhism.

A full discussion of satori would make this post far too long, but suffice to say it is beyond thinking. That is the purpose of kōan, those nonsensical word puzzles used in Zen training such as "What is the sound of one hand?"§: to defy logic and get the student beyond thinking. That is the key. "The tao that can be spoken of isn't the Universal Tao"¶. You can't get at it with words, nor thoughts, only experience. But even that isn't quite right. Because it is words. You are reading and processing them logically. A better Zen teacher might finish that sentence "not words, nor thoughts, only—" by then slapping you. Or ringing a singing bowl. Or chanting Om. Or standing on his head. Or something that to most of us would appear nonsense. To those ready, however, when that hits it shatters their mind and—boom—satori.

For the Buddha it was a star. For Basho, it is a frog. Plop!

Translation

Being that this is the single most famous haiku inside and outside Japan, there are more translations of this one than any other haiku. Just about everyone has a translation, from regular haiku translators to writers of Japan topics, like Lafcadio Hearn and Donald Keene, writers from other fields, like Allen Ginsberg, to Zen philosophers, like Alan Watts and D.T. Suzuki. Many translate it literally, but some instead try to capture something else about the poem.

Literally it says: old pond (古池 furuike) cutting-word (や ya) frog (蛙 kawazu) to jump in (飛びこむ tobikomu) water's sound (水の音 mizu no oto)

The ya at the end of the first line is the cutting word. It has no meaning, yet at the same time it marks a transition and also builds anticipation for what comes next.

Here are some interesting other translations:

Robert Hass:

The old pond—

a frog jumps in,

sound of water.

Lucien Stryk:

Old pond

leap—splash

a frog.

Dorothy Britton:

Listen! a frog

Jumping into the stillness

Of an ancient pond!

Allen Ginsberg:

The old pond

A frog jumping in,

Kerplunk!

Nobuyuki Yuasa:

Breaking the silence

Of an ancient pond,

A frog jumped into water—

A deep resonance.

Lafcadio Hearn:

Old pond — frogs jumped in — sound of water.

Ross Figgins:

old pond

a frog leaps in—

a moment after, silence

Tim Chilcott:

ancient is the pond—

suddenly a frog leaps—now!

the water echoes

James Kirkup:

pond

frog

plop!

John Major:

Ancient silent pond

Then a frog jumped right in

Watersound: kerplunk

Peter Beilenson:

Old dark sleepy pool

quick unexpected frog

goes plop! Watersplash.

Your Call — A Contest (kind of)

Given my own translation at the top of this post, and my commentary, you may be able to guess which ones I like or dislike; regardless, all are interesting interpretations.

How about you guys? What is your own personal translation of this? Looking at the literal meaning (scroll up a bit for my literal word for word translation), thinking of how you interpret the poem, how would you best phrase it in English? I guess this isn't so much translation, but poetry interpretation.

(By the way, that means it doesn't have to be 17 syllables, as you might guess from my own translation and the other examples I used)

Simply leave your interpretation as a comment. If you want to spread the word, please resteem this post too. Best translation/interpretation will win some SBD. Around 2 I think. End time will be a week from now. That is next Sunday (4/1) Japan time.

What's Next

Next is Translation 101, I suppose. I start working towards #200. I may do some kind of pdf collection of all 100 haiku, I'm not sure. Let me know if you are interested in something like this.

Also, my next haiku contest (after I judge the current one) will have something to do with this haiku. Please watch for that in the next few days if you are interested in entering. That one will have much larger prizes than this one.

Thanks

A huge thanks to @geekorner for his help editing this post.

Footnotes:

†: Kigo is a nature word. Traditional haiku all have to have one, typically given for the season the haiku is written in (i.e., if the haiku is written in spring, it must use a spring kigo). Each season is broken up into 3 parts—beginning, middle, end—each has different kigo, though some kigo can be for the entire season. There are thousands of kigo, all categorized in huge tomes for the serious haiku poet.

‡: All school kids have to memorize it. Most probably still remember it.

§: Typically you probably see this as "What is the sound of one hand clapping?" The clapping part is not necessarily correct and I have personally known Zen monks who have told me adding "clapping" entirely misses the point and destroys the kōan. The full kōan is something like "If two hands make a clapping sound, what is the sound of one hand?", so we might see where the typical English translation comes from, but we might also see how it is incorrect.

¶: The Tao te Ching, verse one, my translation. Note: that first tao isn't capitalized on purpose. The first mention is just a word, the second mention is the real thing—which, yes, technically can't be mentioned, so you can think of it as only hinting at the real thing.

❦

| Don't miss other great haiku in the Haiku of Japan series! |

|---|

Recent Haiku

- 91 — Still Laughing

- 92 — Paper, Rock, Scissors

- 93 — Straight Hole

- 94 — Dreams of Cherry Blossoms

- 95 — Doll Faces

- 96 — O Ye Sea Slug of Little Faith

- 97 — Harbinger of Warm Weather

- 98 — Spring Flooding

- 99 — A Child's Hand

Collections

- Collection 1 :: Haiku 1–10

- Collection 2 :: Haiku 11–20

- Collection 3 :: Haiku 21-30

- Collection 4 :: Haiku 31-40

- Collection 5 :: Haiku 41-50

- Collection 6 :: Haiku 51-60

- Collection 7 :: Haiku 61–70

- Collection 8 :: Haiku 71–80

- Collection 9 :: Haiku 81–90

| If you enjoyed this post, please like and resteem. Also be sure to follow me to see more from Japan everyday. |

|---|

I post one photo everyday, as well as a haiku and as time allows, videos, more Japanese history, and so on. Let me know if there is anything about Japan you would like to know more about or would like to see.

| Who is David? | |

|---|---|

| David LaSpina is an American photographer lost in Japan, trying to capture the beauty of this country one photo at a time. |