Sometimes different groups of scientists do similar experiments and come up with different results and different conclusions. For people who have an authoritarian view of science, this can be distressing, as they want a final definitive answer from the experts. But real science doesn’t work that way. Sometimes you end up with apparently conflicting data, and you have to make sense of all of the data together. In general, this is something that humans are bad at, not because we lack the intellectual capacity, but because it’s easier to just discount data that doesn’t fit with the story you have already constructed about other data. People get attached to their favorite theories, and one of the things you have to learn as a scientist is that you have to be willing to modify or sometimes even abandon your favorite theories if the data are pointing in a different direction. I’ve found that when you frame the problem of conflicting data as a puzzle to be solved, students get into it and do a good job at coming up with reasonable explanations that account for all of the data, and even find coming up with potential solutions to the puzzle fun.

That brings us to a study that appears to conflict with other similar studies already published. The question at hand is to what extent prior infection protects against another infection. We have previously seen studies showing between 75-85% reduction in infection, with better protection in the first three months and lower numbers out to about six months. The way these studies are done is to simply look at people who have one infection and see how likely they are to have another one, relative to those who have not had covid (or vaccination). We have also seen two studies where the researchers did this type of study with the addition of antibody readings at the outset, and those both showed that those who were reinfected in spite of prior infection had tested as having low levels of antibodies, so we even have an additional level of analysis.

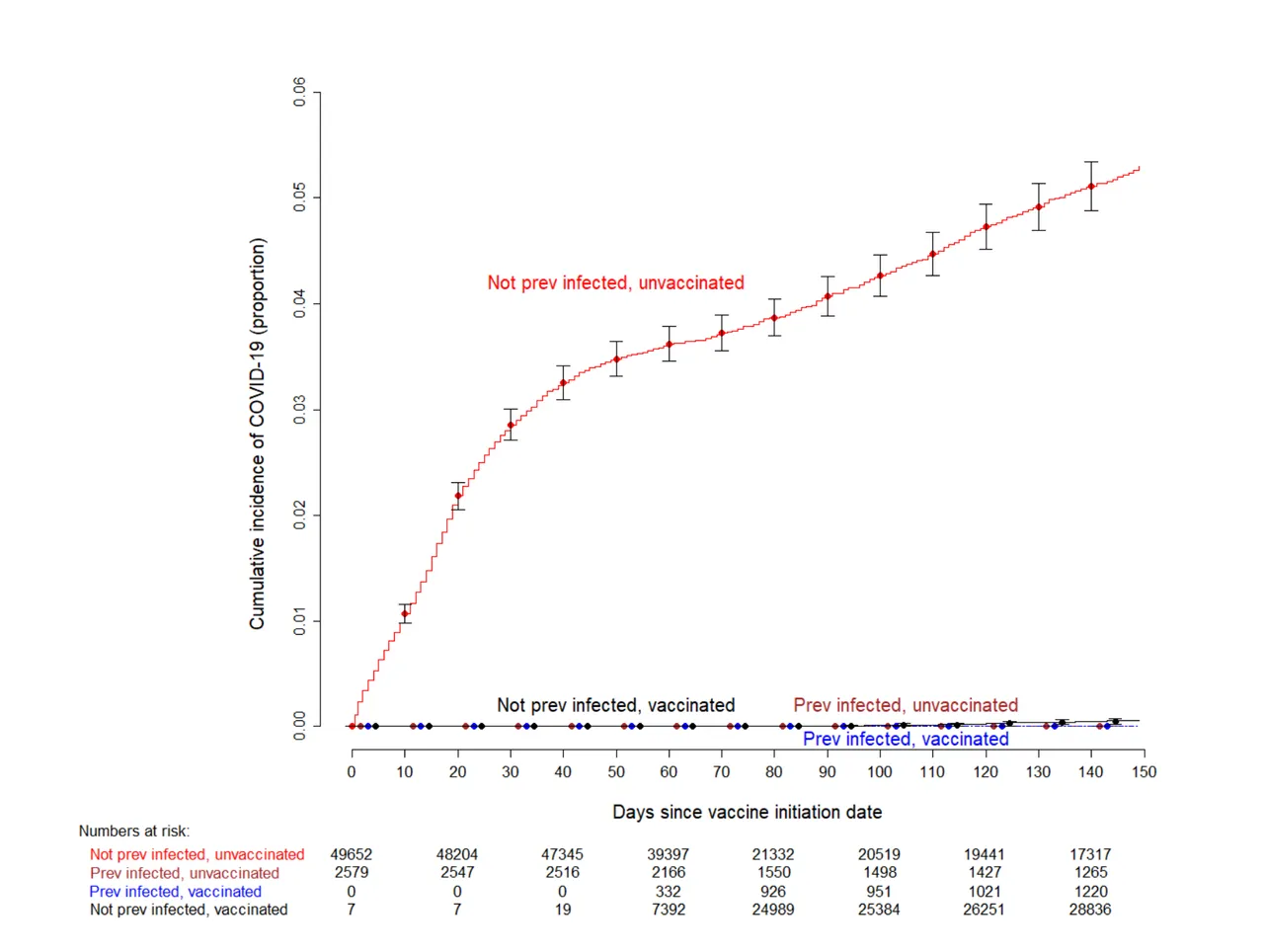

But this new study, with a similar design, came up with different conclusions. The setting is a large hospital system (the Cleveland Clinic) in the US. On Dec 16th, 2020, vaccination of employees in this health system began. Over the next five months, employees were not regularly screened, but those who had symptoms were PCR tested. Most of the employees were vaccinated but there were enough that were not to create four groups of people to be traced over that five month period: never infected but vaccinated; infected and vaccinated; never infected or vaccinated; infected but not vaccinated.

The result was that those that had vaccination or prior infection or both had almost no additional infections. Out of about 1200 people who had prior infection there were no reinfections. That’s pretty surprising given the previous results of similar studies.

So what’s going on here? We’re not going to come up with definitive answers, but we can come up with some reasonable ideas. We need to look at what’s different in this study compared to the others. One thing that pops out immediately is that when the study started in mid-December, only 5% of the employees had prior covid. That’s much lower than the Ohio average at that time of about 20% (based on antibody screening). And the vaccine efficacy at this hospital was very high – 99.3%. So maybe this hospital system is doing something that reduces exposure level of its employees, so that no one would be exposed at work to high levels of virus, and low levels could be blocked by low antibodies. Maybe they have better PPE than the dentists or healthcare workers in the UK. Maybe they have a good air filter on their air handling system. Come to think of it, in the UK, forced air systems are not common, as they can get by without air conditioning, so there might not be any air filters for the UK dental or health care workers. The Marine recruits were in a very high-density living situation, so it’s easy to imagine that they were getting high exposure to each other’s germs, and that the air filtration situation in their living quarters would probably be less good than in a top hospital. In order to test this hypothesis, we’d have to check into the air filtration and PPE situations in the different places where these studies were done, and ideally release some aerosol-sized particles and see how quickly they are cleared. I’d also want to interview people about PPE usage in the different locations.

Another possibility is variants. In Ohio in December, there were no variants of concern. B.1.1.7 only showed up at the tail end of this study. But in the UK, nearly all of the cases would have been B.1.1.7, starting from a few weeks into the study. The same goes for the dentists. This variant is more contagious, and so might be better at infecting people with low levels of antibodies. A point against this idea is that the Marine recruits were in the US before this variant was common. But it’s at least possible that the high level of exposure would have become an over-riding factor. The clearest way to test this second explanation would be to expose people with low levels of antibodies to different variants. That’s technically possible but not ethical, so that one isn’t going to happen. I don’t think that there could be observational studies at this point, because there is very little of the older virus left in the wild.

If the variants are the main problem, there’s not much we can do about it. But if there is something about the air filtration systems at the Cleveland clinic, that could be something that could be useful to implement in other places. Of course, it’s possible that it’s a combination of both of these things.

A third factor is that the Cleveland clinic is not screening for asymptomatic infections, and the study of UK health care workers is. So just based on that we would expect the UK study to find more reinfections. However, the UK study of dentists was similar to the US study in that they were looking only for symptomatic reinfections. So that's not all of it.

The conclusion of the authors is that we should wait to vaccinate those with natural infection until high-risk people in India and other parts of the world with covid but few vaccines are vaccinated. In general, I agree, although I would want to actually test people with prior covid to make sure that they have antibodies at levels likely to be protective, and vaccinate those who don’t. It’s my understanding that the US is starting to send more vaccines overseas, although it still seems ethically problematic that we clearly have so much excess here when they are needed so badly elsewhere.

Link to study: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.01.21258176v2.full.pdf