It was supposed to start this coming week, but Pfizer is shifting it to the following week in order to get their paperwork in order.

As I mentioned before, the design of the study is to give 10,000 people who got their shots at least six months ago (in the trial) either a booster or placebo, and follow them for symptomatic covid until there is a good-enough difference in the rate of symptomatic infection between the groups or one year, whichever comes first.

The control (placebo) group of 5000 people will, of course, still have antibodies. They had their second shot on average about 9.5 months before the start of the booster trial. But they are slowly wearing off.

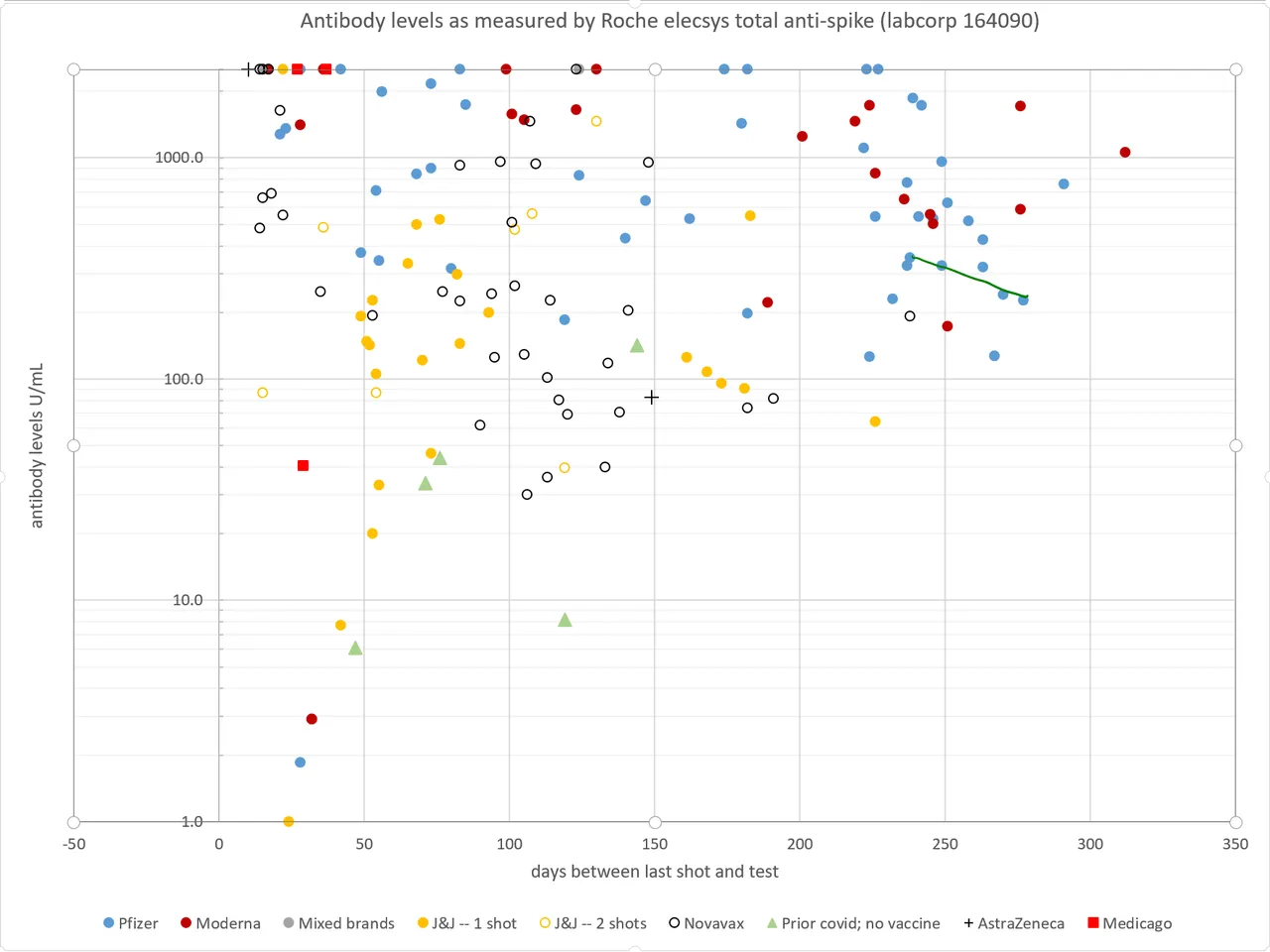

I went and got a second antibody reading so that I could calculate a half-life of my antibodies in the past month or so. It came out at 68 days. We don't have any published antibody half-life data on Pfizer, but for Moderna, it was 52 days starting after day 42. Because the decay rate tends to slow over time, 68 days for the 8-9 month range seems reasonable. Unfortunately, I don't have any antibody half-life data on anyone else in the Pfizer trial other than myself. But eyeballing my data points on the graph, it looks like the rate of my antibody decay is similar to the overall trend over time for Pfizer. I will put up a chart with my data points connected by a line.

At 8 months, the average antibody level (on the Roche scale) is about 600. Assuming a half-life of 62 days, that means at the start of the trial in early July, the average will be about 360. That is consistent with efficacy in the 80-85% range.

After six months, levels will be down to the upper 40s, which correlates with about 60-65% efficacy.

So over the first six months, we're looking at an average efficacy of about 70-75%, although it will be higher at the beginning and lower at the end. What that means is there will only be about 25-30% of the covid cases that you'd expect in a population without immunity.

Trying to calculate the infection rate in those who have immunity now is actually pretty complicated. About half the population of the US has at least one shot of vaccine, and about a quarter of the population has antibodies from infection. Of course, those two groups overlap somewhat, but we don't know how much. In general, states with higher infection rates have lower vaccination rates, and vice-versa. But ballpark, about a third of the population still has no immunity. If 90% of the cases happening now are in that group, their risk of infection in a month is about 0.3%. Out of 5000 people, you'd expect 15 infections per month. But because our placebo group is vaccinated with waning antibody levels, it would only be about 4 cases per month.

If over six months, they get 24 cases in the placebo group and only one or two in the booster group, that will probably be enough to call the trial a success. It would put the efficacy of the booster at more than 90% relative to the people who were relying on their waning antibodies from the first two shots.

Of course, all of this is very rough calculations based on the infection rate in the US today, and not all the study sites are in the US. There is also the possibility that the delta variant will cause an increase in cases that will speed things up. Six months forward puts us into holiday season again, and it's possible that we will get an increase in cases then, which will also speed things up.

On the other hand, we are past herd immunity for the alpha variant in the US, and close to that point for delta in some states. So it is possible that the US will reach herd immunity for delta through infections in the next six months. If that happens there won't be enough cases here to measure efficacy and the trial will probably fail due to lack of data.