Published by Orbit Books and written by Daniel Abraham, The Dagger and the Coin comprises The Dragon's Path, The King's Blood, The Tyrant's Law, The Widow's House, and The Spider's War.

The series focuses largely on five characters: Captain Marcus Wester, a grizzled mercenary captain, a veteran of war who saw his wife and daughter die in flames before his eyes. Cithrin bel Sarcour, a banker raised by the Medean Bank thrust unexpectedly into far greater power and danger than she ever expected. Geder Palliako, a minor nobleman of Antea who by luck and happenstance, and the political scheming of others, rises to become a hero to the country, protector of the prince, and Lord Regent of Antea. Clara Kalliam, the (eventually) widowed wife of a nobleman who stood against Palliako, and who is instrumental in putting together the eventual resistance. Finally, appearing for the first two books, the conservative nobleman Dawson, a staunch traditionalist deeply loyal to king and country and the ideals of honor and duty as he sees and understands them, and whom is executed in the second book.

It is set thousands of years after the fall of the dragons who created the thirteen races of humanity: Firstblood, the "base clay" of humanity; Jasuru, Yemmu, and Tralgu, the Eastern Triad; Cinnae, Dartinae, and Timzinae, the Western Triad; Kurtadam, Raushadam, and Huanadam, the High Triad; Haaverkin, Southling, and the Drowned, the Decadent Races; as described by a Kurtadam scholar in An Introduction to the Taxonomy of Races.

This post is, in part, commentary, analysis, and overview. I will repeat what I said at the very top just to be sure: this article contains spoilers for almost every aspect of the series, from storyline to character development to worldbuilding. If you have not read the series, or are only part way through, and do not want spoilers, do not read this. I repeat: This article contains spoilers for basically everything in the series. There are also spoilers of varying detail for other works of speculative fiction. You've been warned.

Though it should be obvious, this is not a formal, scholarly analysis, as I am not a scholar. Unless indicated otherwise, all of the quotes come from Daniel Abraham.

| Race | Description |

|---|---|

| Firstblood | the base clay; the most populous of races, having the least difficulty in procreation. |

| Jasuru | share the size and shape of Firstbloods, but with the metallic scales of lesser dragons. |

| Yemmu | huge in size, with massive tusks, clearly meant to intimidate; has the shortest natural lifespan of the races. |

| Tralgu | taller then a Firstblood, with fierce teeth and a carnivore's hearing, likely meant for hunting. has difficulty in procreating. |

| Cinnae | thin and pale, with a talent at the mental arts. |

| Dartinae | generally lithe, with luminescent eyes, meant for mining. |

| Timzinae | dark, insectile scales capable of utterly encasing the living flesh to the point of covering all bodily orifices. |

| Kurtadam | a Cinnae's cleverness, the Eastern Triad's warrior's instinct, and unique among the races, a warming pelt. |

| Haunadam | their skin has a thick mineral layer and they have an aversion to travel by water. |

| Raushadam | slightest in frame, they are the only race gifted with flight. |

| Haaverkin | clinging to the north, this foul-tempered race is large as a Yemmu thanks to rolls of insulating fat. their thick tail enables them to swim through cold water. |

| Southling | making their home in Lyoneia, they have delegated the practice of procreation to a queen. their wide eyes are adapted for night. |

| the Drowned | they live exclusively underwater and communication when possible is slow. |

One of the most unique aspects of worldbuilding in The Dagger and the Coin is the choice to populate the world with thirteen different races of humanity. Unlike today's false conception of race (really just the presence or absence of skin pigmentations and minor differences in physical features), the thirteen races truly are different: some are scaled, one has glowing eyes, the society of another is like that of termites.

Further, while some of the species can interbreed, others can not. The half-breed results of such are, themselves, often infertile.

Within the series, our viewpoint characters are all Firstblood, excepting Cithrin, who is half-Cinnae. We meet or see at least one member of every race except for the Haunadam and the Raushadam, whom both reside in Far Syramys.

Part of what I wanted to do with the races in Dagger & Coin was get that feel of being in fantasyland back.

So the different races of humanity add texture and color to the whole book. The thirteen races live together in relative peace, with a shared culture, history, and language. Some races are more common in some places than others - the Timzinae of Elassae and Sarakal, the Haaverkin of Hallskar, the Southlings of Lyoneia - but often you will find a Cinnae and a Dartinae and a Firstblood and a Jasuru walking the streets.

Nevertheless, there's a subtle but powerful undercurrent of racism that runs through the story. Mentioned many a time are acting troupes, and of course, Master Kit and his acting troupe are part of the prominent supporting cast. One such play is PennyPenny the Jasuru - penny a derogative for the Jasuru.

They aren't the only ones. The Kurtadam, with their pelt and their beading, are called clickers. The Southlings, with their wide eyes, are called eyeholes. And the Timzinae, with their insectile scales, are called roaches.

Many races do have unique cultures. The Timzinae of Sarakal and Elassae, and of Suddapal, seem to have a very familial type of society, as the many family compounds at Suddapal reveal. The Haaverkin keep to Hallskar, their thick rolls of fat unsuited to the 'southern' climate. During The Spider's War, Karol Dannien's second is a Haaverkin. True to the description, he's rather grumpy, but he is, ultimately, effective.

In The Tyrant's Law and The Widow's House, Marcus and Master Kit actually visit Hallskar. Their society is set up somewhat more tribally: various Orders have their own chiefs and different rituals for becoming a man. Governing all of them from the capital of Rukkyapal is a High Council: at the beginning of The Widow's House it's revealed that they're drawing up plans in preparation for the day Antea wants Hallskar, and so they've decided that they as may as well take the taxes and temples "friendly-like."

In The Tyrant's Law, Marcus and Master Kit visit Lyoneia, searching for a culling blade with which to kill spider priests. Lyoneia is inhabited almost entirely by Southlings, and meeting them is an unusual occasion: the Southlings are adapted for life at night, and so as darkness falls on Marcus and Kit more Southlings appear.

The small village where they eventually make their way too seems to have more people then could possibly fit into the huts, so the Southlings likely have underground structures. The taxonomy (linked to above) describes the Southlings as delegating procreation to a queen figure. In Tyrant's Law she is called the village mother.

Finally, everyone expresses distaste for the Drowned. Long journeys to Far Syramys may result in sunken ships upon return, upon which everything would be lost, or, as described in Dragon's Path, ransomed back at "exorbitant rates and glacial slowness" from the Drowned. In Cithrin's last chapter in Spider's War, with Geder Palliako's great war ended, she observes that the Timzinae will still be called roaches by some, Yemmu would still disdain the Tralgu, "the Cinnae, the Kurtadam; and everyone everywhere, the Drowned." From all this we can gather that the Drowned are held in disdain, dislike, and distaste by the twelve other races of humanity.

Details like these - the Orders of Haaverkin and their High Council, the Southlings' underground homes and village mother, the nigh-universal distaste for the Drowned - are presented simply as facets of the world, rarely if ever accompanied by summarizing passages to familiarize the reader and explain it. It's presented to the reader as though the reader were from the world itself. For some it be alienating. For my money, it's more immersive.

It's a fantastic detail of worldbuilding, rendering humanity at once more diverse and more alien then humanity as we know it. The skin of Firstbloods' are described as ranging from pale to "dark as a Timzinae's scales." We can safely assume that Firstbloods have as much range of pigment as our own humans do, but, with twelve other races of great variety and diversity, they never developed a pigment-based racism.

Another, minor note: in the epilogue of The Dagger & the Coin (the last chapter of The Spider's War), Master Kit and the acting troupe prepare to head for Far Syramys. Far Syramys, of course, is the home of the Raushadam and the Haunadam, but it seems that there are other differences: Master Kit describes tales he has heard - "the Tralgu who live there have fox ears, and the Southlings speak in languages that no one but they can understand."

So there may be more diversity even that that. But within the book itself we never visit Far Syramys. But we don't really need to: there's more than enough variety just by the races alone to give the world a unique and distinctive color and texture quite different from many other fantasy worlds.

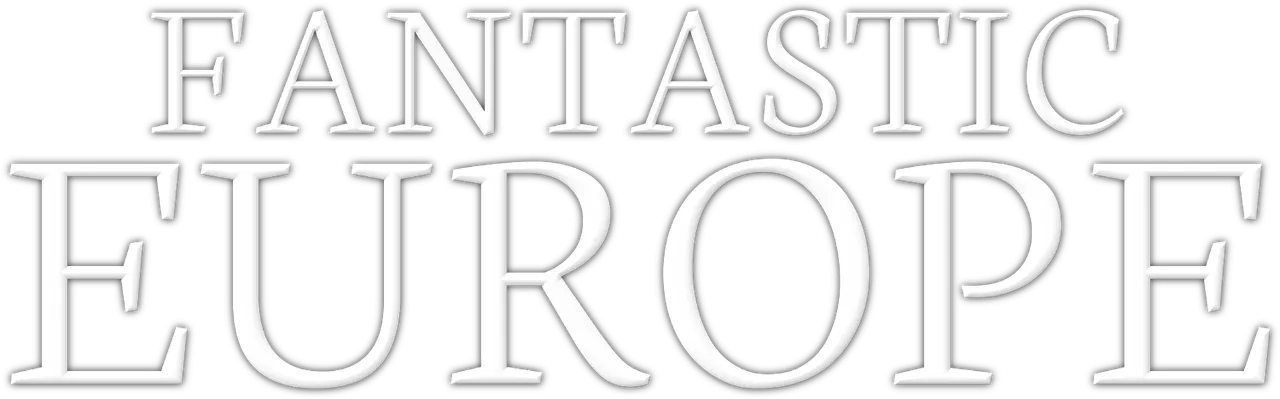

As the above map may indicate, the world of The Dagger and the Coin is largely based upon Europe.

In no particular order...

Hallskar, home of the Haaverkin, of course stands in here for Scandinavia: a cold, unforgiving place with great snowstorms and choppy waters, in which any visiting Firstblood would probably be thought an idiot for coming and a sorry sight.

Narinisle, though it is never visited, naturally stands in for Britain. Herez and Cabral stand in for medieval kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula, Princip d'Annalde apparently standing for Brittany. Birancour is our guest France, while Borja, Sarakal, Elassae, and the Keshet can't quite be pinned down.

The Free Cities, of course, stand in for Italian city-states. Far Syramys, never visited within the books and not present on the map, corresponds geographically to the Americas. Lyoneia of course is "Africa" - jungle- and insect-infested and inhabited by strange peoples (the Southlings).

Northcoast has elements of France and England. It may at first be odd that it the Medean Bank's holding company, an obvious counterpart to the Medici Bank, would be based there rather than in one of the Free Cities, but the reasons become clear later: when Cithrin invents central reserve banking, the Medean Bank transforms into an analogue of the Bank of England.

Historically, the Dragon Empire takes the place of the Roman Empire, complete with eventual decline into decadence, though its end - a final war between the dragons resulting in the deaths of all involved (Inys excepted) and the creation of the spiders by Morade - leaps out as quite fantastical.

The greatest and most obvious analogues are Antea and Asterilhold, each once part of the same empire before dividing - Germany and Austria, once part of the Holy Roman Empire. More specifically you could label Antea as not merely Germany but Prussia for its miltarism.

The two countries share many cultural and familial ties such that, if you removed enough people, someone of Asterilhold (no demonym is ever provided within the series) could lay claim to the Severed Throne of Antea. An effort to kill the King and Prince of Antea, so as to unite Asterilhold and Antea, is an important plotline during The Dragon's Path, and the aftermath of that scheme is itself important also in The King's Blood.

One of the aspects of The Dagger and the Coin that makes it truly unique among fantasy is that it doesn't just draw from the typical medieval Europe theme. No, Dagger and Coin draws also from World War II, something far more recent and therefore far more unique a source for fantasy to draw upon.

Dawson was originally based on Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen, a German royalist who hated the Nazis because they were of the wrong social class. The line that stuck in my head was talking about the nazis as "the revolution of the housepainters." He wrote a book that was published as The Diary of a Man in Despair. I was really taken with the idea of a character so far on the wrong side of history that he lapped himself.

Remarked above I compared Antea and Asterilhold to Germany and Austria, and the comparison stands through to the parallels with WWII: Asterilhold is the first country to be conquered by Imperial Antea after Geder takes power as Lord Regent, just as Austria was the first country taken by Germany.

But the war itself is not WWII through a cracked mirror: Imperial Antea does not move on to Birancour (France) but instead turns it attention east, to Elassae and Sarakal and Borja. There is no equivalent to Russia or Britain or Belgium here. Instead, we will turn our attention to the prime motivators behind the war.

Lord Regent Geder Palliako and the dangerous forces behind him, the Cult of the Spider Goddess.

The Cult will be discussed more later on, but for now: the priests of the cult have spiders in their blood and so, when they hear someone speak, can detect certainty. They, however, think that they can detect truth, and so it is their view of the world which is correct.

Dissent, naturally, is not tolerated - the rule of the Lord Regent and of the spider goddess is, and must be, absolute.

Remind you of anybody?

It gets more insidious. The way the spider priests work is that the spiders get into the blood of initiates: they then "purge" the initiation of lies. (In fact, they purge the initiate of the ability to doubt themselves.) This only quite works on twelve of the races of humanity. One race, created at the very tail end of the last war, at the fall of the Dragon Empire, can resist: the Timzinae.

A re-read was rewarding in this respect. It's only in The Tyrant's Law that the spider priests began acting against the Timzinae, but if you go back to The King's Blood, one chapter talks of rumors that Dawson Kalliam (who attempted a coup against Geder) was allied with Timzinae. (Dawson would never've done that, as his wife can attest to. He's too, ahem, "traditional" for that. Read: racist.)

From the third book onwards, the Timzinae are persecuted by Imperial Antea. In Tyrant's Law Geder begins having prisons build. It's later on that their purpose becomes apparent: Timzinae adults are taken as slaves for Antean farms, while Timzinae children are kept in those prisons as hostages.

In time, it evolves. The Timzinae hadn't just been collaborating with Dawson but with all the enemies of Antea. It's a vast, wide-ranging, world-spanning conspiracy, all rooted in the Timzinae.

In Spider's War, Geder finally crosses the line - if he hadn't already - when Karol Dannien's army emerges as a force to be reckoned with (along with other "Timzinae armies" in Sarakal and Borja), Geder feels he is forced to act. And so hundred of children are thrown down the Division which goes through Camnipol - thinking that he has to show that Antea doesn't go back on its word, that he has to show Antea's strength.

Another trait of Dagger and the Coin is that it subverts some familiar fantasy archetypes. As you've read above, its diversity of humanity and drawing upon 20th-century history for its world and story already distinguish the series relative to other fantasy.

But its characters also subvert a number of familiar fantasy tropes and ideas.

Cithrin bel Sarcour, perhaps the central protagonist of the entire series and one of the driving forces of the rebellion against Geder, is, indeed, an orphaned child: she never knew her parents nor any other family. But, where so many other fantasy orphans are left with malicious relatives, or kind relatives, or iffy orphanages, Cithrin was a ward of the Medean Bank.

Growing up surrounded by the machinations of merchants, the economics of politics and the politics of economics, gives her a singularly unique outlook on life. She thinks of much in the terms of how it works economically - but the drawback is that she sometimes struggles to connect with people. (This forms a good part of her character development in Tyrant's Law, where she apprentices far from where she's familiar to the city of Suddapal.)

Her response to struggle and difficulty is also not typical. Can you imagine if Harry Potter became a high-functioning alcoholic? From the tail end of Dragon's Path onwards, Cithrin struggles with alcohol and by the end of the series she still enjoys her wine just a touch too much.

(In diametric opposition to Cithrin's "coin" is Geder, the "dagger" of the piece. More on him, later.)

Our perspective on the Antean court is subverted. Our viewpoint comes from Dawson Kalliam, a reactionary noblemen fully possessed of the belief that the commonfolk should remain in their place and that it is the right of the nobleman to rule over the commoner. Following through all the way, Dawson is rather racist: he would've never conspired with the Timzinae.

It's Dawson's middling politicking that allows Geder to come to the position he ended up in: maneuvering him into Protector of Vanai, setting the stage for Geder to burn it to the ground; choosing to welcome Geder as a hero for the act; and after the chaotic season of court, working with Geder to foil the plot to kill Prince Aster, and so allowing Geder to become Aster's warden, and, through that, Lord Regent.

One of Dawson's political opponents is more representative of the typical heroic nobleman: Issandrian, who is fighting for a farmer's council. Dawson, of course, disagrees with the idea that a pig farmer should be let to run society.

In the end, Issandrian was allied with the group trying to kill Aster, though Issandrian himself didn't know anything about that aspect, which was entirely down to Feldin Maas.

What in Dawson allows us to sympathize with him? His loyalty to his country, colored though it may be by a deep-rooted belief in Antean superiority. His sense of duty and honor, even though he is blind to the inconsistencies of his application of it. And his love for his wife, which is utterly pure and true.

In the end, he realizes at least part of the problem with the new Lord Regent. Observing carefully, he notes Geder watching for the spider priest's nod, and so takes it to mean that Geder is now under the influence and control of foreign priests. And so he launches a rebellion. See the quote from the previous section about Dawson: "[...] a character so far on the wrong side of history that he lapped himself."

I'm skeptical of subversion for subversion's sake. I think that there's a real pressure to subvert the genre out of a sense of almost shame. It can be like a preemptive apology. I've done things that are different, but I've done them in an effort to reach the same places and effects, so I don't think of it as subversive.

In his wife, Clara, we find more that is unique. In The King's Blood, Dawson is executed by an angry Geder, leaving Clara a widow. With Dawson dead, we are left with four viewpoint characters: Cithrin, Geder, Marcus, and Clara.

Clara is by no means a traditional fantasy protagonist at all: she is neither a nor an orphan, nor a nobleman, nor a mercenary, nor even a businessman. She's instead a middle-aged woman, left widowed and shunned socially. Of all the characters, she is the only one with a romantic storyline, as she falls in love with Vincen Coe, someone both younger than her and lower in social status.

She's vital in putting together the resistance to Geder. Throughout The Tyrant's Law she works to undermine Geder, mimicking another nobleman to get his Lord Marshal killed while also writing letters to the Medean Bank. In Widow's House it is she who brings her son Jorey, the new Lord Marshal, to Cithrin's side. And in Spider's War, she is the first to think about what to do after the threat of the spider priests are ended.

And as for Marcus Wester... truth be told he doesn't subvert much at all. He's straightforwardly the grizzled mercenary captain, his wife and daughter killed before his eyes, yet attracted to good causes regardless. (Largely on the basis that Cithrin reminds him of his daughter.)

I said before that Geder would be discussed separately. I'll begin with the twist on a classic fantasy trope: the Chosen One. Geder, the villain of the series, is the "chosen of the spider goddess." The spider priests were waiting for a sign to come for them to return to the world, and Geder's arrival, searching for the Righteous Servant, was that sign.

The Geder we meet in Dragon's Path doesn't change much from the one we meet in Spider's War. But it's worth noting how much is foreshadowed: his anger, his sense of unjust humiliation, emerges early on at Sir Alan Klin. In later books, he insists that Klin serve in the vanguard: a dangerous position to be in. Klin himself puts it this way, paraphrased: "My life has less value to him then a book."

Perhaps his greatest issue is that he can not accept blame. Everything is somebody else's fault. In Vanai, with Klin as Protector, he is made tax collector, an unpopular job that leaves the populace hating him. And when he himself becomes Protector, he wants to make amends - by apologizing to the populace, saying that he had been forced to do those things. In Spider's War, he finally does realize that things are his fault and the result is one of the most terrifying passages in the book as he flies through sobbing and then furious laughter and then screaming. It's a terrifying page and a half.

The author himself has said, had he not been rewarded for burning Vanai, had he had a mother - his father, Lehrer, did his best but it's clear that he's not very nurturing, wasn't prone to punishing Geder when he did ill - he would've probably been a great guy.

Geder was easy to write. He's very familiar to me, and to a lot of people, I think. A lot of us have been Geder, it's just that most of us have grown out of it.

And as much as we see his flaws - his anger, his vengefulness, his pettiness, his willingness to be lead by Basrahip - we do see some of his merits. He's reasonably intelligent, having read many history books and speculative essays. He's loyal to his friends - appointing Jorey Kalliam as Lord Marshal when the former had little experience leading men, purely on the basis of their friendship, and to rehabilitate Jorey in court. He's kind. His relationship with Aster is one of the most precious things in the books, watching Geder handle Aster with sometimes surprising maturity and ability.

Geder doesn't really have a good sense of self-awareness. He executes Jorey's father, and immediately afterwards - blood still on him - asks Cithrin to tea. Jorey, caught between a rock and a hard place, turns his hatred of what Geder has done into a twisted loyalty - made easier by the spider priests' ability to convince those who hear their voice of what they say.

When Lord Marshal Jorey goes off to war, he develops a friendship of Sabiha, which is at once touching here and terrifying there. His power as Lord Marshal allows him to bring in his own personal cunning men (magicians) when the birth of Sabiha's daughter looks like it might be dangerous for child or mother. For the reader, the problem comes in remembering Geder's possessiveness: what if he somehow comes to the conclusion that Sabiha is his?

He badly desires love and friendship. It is this, in part, which leaves him so set on staying friends with Jorey, which leads him to so desire Cithrin. It is what makes Basrahip such a dangerous figure, because his ability to reveal truth on Geder's command turns Geder into a hero even further, and the victories in the war make him acclaimed. He drinks it up like a man starved for water.

It is, ultimately, this desire for love, and this vengefulness, which lead to his defeat: allowing Cithrin and her allies to convince him of the true nature of the spider priests, and then to allow them and aid them in killing the spider priests.

How might have Geder turned out better? A mother that could've punished him we did wrong. But, instead, Lehrer Palliako, without a wife, did the best he could and could never bring himself to punish his dear boy.

Or if, upon burning Vanai, a city of so many people, he had not been welcomed to Antea as a hero but instead punished for it and made to realize the awfulness of that act. Instead he was welcomed as a hero, and so his twisted sense of morals never got to untangle itself - and if he had not crossed the moral line in launching a war against the Timzinae, in enslaving their adults and imprisoning their children, then surely he crossed it when, after the Timzinae began rebelling, he had hundreds of Timzinae thrown down the Division.

In the end he is a villain who but once never realized he was a villain. An accidental tyrant, a kind monster. A villain protagonist - and following his perspective is at once interesting and terrifying and even sometimes rather sweet, his flaws always contrasted with his positive qualities to leave him sympathetic even up to the very end.

In so much of traditional fantasy the movers and shakers of power are kings, princes, knights, warlords. For a long time the importance of the merchant and the bank was not recognized. That's not to say money didn't factor into it: just look at The Hobbit. But suffice to say, economics were not very central. Money might've been, but genuine economics wasn't.

As the twentieth century has rolled on into the twenty-first, exceptions have emerged. 1995's Rise of a Merchant Prince, by Raymond E. Feist and the Iron Bank in A Song of Ice and Fire, for one. I've not read the former, but the Iron Bank is an extremely powerful institution on the Planetos, such that's it's a known saying that "the Iron Bank always collects its due."

Ruling is hard. This was maybe my answer to Tolkien, whom, as much as I admire him, I do quibble with. Lord of the Rings had a very medieval philosophy: that if the king was a good man, the land would prosper. We look at real history and it’s not that simple. Tolkien can say that Aragorn became king and reigned for a hundred years, and he was wise and good. But Tolkien doesn’t ask the question: What was Aragorn’s tax policy? Did he maintain a standing army? What did he do in times of flood and famine? And what about all these orcs? By the end of the war, Sauron is gone but all of the orcs aren’t gone – they’re in the mountains. Did Aragorn pursue a policy of systematic genocide and kill them? Even the little baby orcs, in their little orc cradles?

George R.R. Martin

Money and finance forms a running thread through the Moist von Lipwig stories of Terry Pratchett's Discworld series, most prominently in Making Money. Abraham himself has shown strong consideration: in his previous series, The Long Price Quartet, the andat aren't just a cool idea (though they most definitely are that), they're deeply ingrained into the way the world of Long Price works.

Other modern authors, even if they do not focus on it, at least acknowledge it: Sanderson, Rothfuss, Scott Lynch. Joe Abercrombie with his First Law books and the bankers Valint & Balk.

Aside from Feist's book, however, I doubt that economics and banking have been so central to a series as they are with The Dagger and the Coin.

Cithrin bel Sarcour is the "coin" to Geder's "dagger", on a personal level, and on a larger scale the Medean Bank is the coin to Imperial Antea's dagger. The beginning of the series leaves the bank's power just implied: Cithrin is their ward, which says a lot in and of itself. But as the series go on, it becomes more and more prominent how powerful the bank is: their money funds armies.

It's truly in Tyrant's Law that the power of the Medean Bank emerges. The bank at Suddapal is larger then that of Porte Oliva or Vanai, and more influential. The Timzinae live in compounds that house multiple families. The community is therefore linked with each other.

As Geder's war against the Timzinae - against Elassae and Sarakal - picks up, the bank at Suddapal turns itself not towards the saving and storing of money but to the expending of it. Under Isadau, the underground railroad is set up. When the Antean army arrives, Cithrin takes her place, utilizing her influence to gain the freedom to do what she likes without oversight, thus saving many, many more Timzinae. She departs only when she realizes that she can't bear to become Geder's consort.

From there the war turns itself towards Birancour, where Cithrin has returned to Porte Oliva. The Bank continues to act in the shadows against Geder, setting up the fictional Callon Cane and setting bounties on Antea soldiers, spider priests, and even on Geder himself.

The Bank funds flyers, sheets of paper describing the nature of the spider priests, urging people to cut thumbs to make sure that spider priests do not infiltrate the ranks.

At the tail end of Widow's House, and across Spider's War, Cithrin invents central reserve banking and paper money. And it becomes clear, too, that the Medean Bank will only grow more powerful as a result of this, since they control the issuance of currency.

Many of the books feature descriptions on the nature of exchange, of debt. This may not be to everyone's taste, but it certainly was to mine: I found it fascinating and enriching, and that recognizes the importance of economics and financial institutions - and not only that but features it so prominently - once again makes it unique.

Of all that runs through The Dagger and the Coin - the parallels with World War II, the economic might of banking, the pettiness of evil, the diversity of humanity - one of the biggest, perhaps - probably - the biggest, is the nature of truth.

The Lord of the Rings was a massive epic fantasy about disarmament and the cost war has on the individual. A Song of Ice and Fire is among other things an essay on the futility of war. he aspect that I've taken in The Dagger and the Coin is the way that the story of a war, be it propaganda or history, outstrips the war itself.

The ancient evil is the spider priests. A remnant of the final war between the dragons, that saw the end of them. The spiders were created by Morade as a tool to spread chaos among the slaves. (Humans, who were created by the dragons.) The spiders, you see, purged the ability of someone to doubt. What can spread more chaos then being totally and utterly convinced of the righteousness of your beliefs, your ideals, your worldview?

At the end of the war they were banished and so they went far east, to the Keshet, where they set up a temple in the - relative - wilderness. Over time, they came to believe that they were created not by the dragons but instead were servants of the Spider Goddess, that the Timzinae - the only race that could, through their chitinous skin that could grow over every orifice of their bodies - were part-dragon, and finally, that they were awaiting a sign to return to the world.

Through their voice, they could make others believe that they were correct, make those without the spiders believe what they said. And they also came to believe that, through the spiders in their blood, they could distinguish truth from lie in the living voice.

It is this dangerous power placed in the hands of entirely the wrong person that allows the Timzinae to be persecuted as part of the spider goddess's "purification" of the world.

There are many conversations during the series about the nature of truth and lies and certainty. Especially with regards to the folly of certainty. One of my favorite lines is from King's Blood, from Master Kit, an apostate. "I dislike certainty because it feels like the truth, but it isn’t. If justice is based on certainty, but certainty is not the truth, atrocities become possible." Kit realized the truth of the spider priests when he asked an old man who cleaned the floors if he had done so. The old man said yes, and Kit took it as truth. But when he happened across those same floors, he found they were not, in fact, cleaned.

The old man couldn't have been lying. The spiders in Kit's blood would've said so. But he was not telling the truth, even though the spiders gave the indication he was. In truth, the old man merely believed truly and fully that he had cleaned the floors. It was then that Kit realized that he could disagree.

Alone at a far corner of the map, in the Keshet where no one had ever really heard of them, the spider priests were not particularly dangerous. But brought back to the world, they become more dangerous, because they need more priests, as the few from their temple in the Keshet were not enough. And so they induct Anteans.

The consequences we see in Widow's House when a schism emerges, a spider priest claiming that he is the true voice of the spider goddess, not Basrahip. Isolated in the Keshet, all the spider priests could hold the same beliefs, time and isolation ensuring they did not differ. But when they induct Anteans from all over the empire, who don't have that isolation for centuries behind them, the inability to doubt and dissent, the absolute self-belief, becomes even more dangerous. Each Antean brings in their own different opinions and ideas, and because of the spiders, these opinions become fact in their eyes.

The tangible danger is that if the taint is not removed the spiders will spread, and spread, and spread, until they cover the whole world, turning it into a world where each individual is pitted against every single other individual, each just as convinced of their righteousness as the next.

(As an interesting side note, women can not become spider priests. The spiders in the blood, you see, would be... dangerous and introduce, ahem, complications during menstruation.)

This theme, I think, is particularly important and relevant in our time, perhaps even more so then during their initial 2011-16 releases. It was a modern theme to begin with: the Bush administration selling the American people, lying to their faces, and dragging us into a war from which we still have not emerged. The succeeding Democratic administration obstructed at every time by conservatives wholly convinced of the correctness of what they're doing, all too often unwilling to compromise.

But here in 2018, and even back in 2016, it took on greater importance as we moved ever closer to today, the hero and now, an era in which, at the highest levels of American (and to a lesser extent British) government, truth and fact have ceased to have any meaning or relevance in favor of the personal beliefs and worldview of the people inhabiting those positions.

The danger of absolute belif is shown both ways, in Karol Dannien, who leads the "Timzinae army" against Imperial Antea. Much of Spider's War focuses itself on ending the war and trying to ensure that Dannien's army, which wants justice for the persecution of the Timzinae, doesn't take an unjust vengeance against Antea that will only leave both sides hating each other and ensuring there will be more wars in the future.

The Dagger and the Coin, then, shows the danger in absolute belief. Absolute belief is not good. Absolute belief in one direction will alienate those who disagree and entrench them further into their own positions until both sides are possessed of absolute belief, until both are completely certain of the righteousness of their beliefs and ideas and principles.

I think moral certainty and simplicity are gateways to atrocity.

What of the surroundings? Abraham himself has been quite open about his influences. Some of them are more obvious than others, of course.

The reader will of course conclude that A Song of Ice and Fire has been a big influence: you can liken the character of Dawson to Eddard Stark and the former's wife Clara to Catelyn Stark. Dawson, like Ned, was killed, though the circumstances are quite different, and Clara's path is far, far different from Catelyn's own. Even the term Severed Throne matches up to the Iron Throne, and, like Planetos, Dagger & Coin has its own Free Cities.

Naturally, there are many differences. Eddard is presented as noble and honorable, having lived through a rebellion. Like Dawson, he is friends with his King and deeply loyal. But we never see much of his political views because Ned, who comes from the North, is unfamiliar with it. Dawson, on the other hand, politicks his way through the entire series while alive.

You could make the argument that Dawson is not very good at politicking, as it is his actions that lead to Geder's rise. But he shows talent for adapting to new situations and a very deep loyalty not just to King Simeon, a friend during his boyhood, and Simeon's son Prince Aster, but also to Antea, his country and home, and to the ideals and principles that he considers Antea to uphold and embody.

Clara, similarly to Catelyn, loves her children. But unlike Catelyn her children are largely grown, and none of them are killed, so grief over the loss of her children is far lesser than with Catelyn. But grief still is present, and Clara mourns Dawson in the latter end of King's Blood and almost the entirety of Tyrant's Law.

Much of Clara's story comes in her behind-the-scenes politicking: aiding her husband not by skirmishes of sword but by the society life of the ladies of the court: what questions are asked? who wore the prettiest dress? what topics are hinted at? After Dawson's execution she goes underground, writing letters to the Medean Bank, even, as a letter-writer, impersonating one of the Lords in Geder's service.

The Severed Throne itself is a far cry from the Iron Throne. It is named for the great Division that runs along Camnipol, but of the throne itself we do not see as much. It is not nearly as distinctive an object as the Iron Throne is. It doesn't need to be.

The influence here is obvious, but differences ensure that Abraham remains unique.

If you're familiar with science fiction, particularly television science fiction, Babylon 5 is another very clear influence. Geder, and the influence of Basrahip and the spider priests, match up to Londo Mollari and the influence of Morden and the Shadows. Having not seen Babylon 5, I can not make further remarks on the subject.

Finally, there are a number of others. The dynamic between Mal and Zoe in Firefly is clearly reflected in that between Marcus and Yardem. Abraham himself has also mentioned the novels of Dorothy Dunnet, and Tim Parks' book Medici Money. He's said that he essentially took his favorite bits of all his favorite things and wrote that.

Right! And now for some sources. Those are fun.

The books themselves: The Dragon's Path, The King's Blood, The Tyrant's Law, The Widow's House, and The Spider's War.

This three Reddit Ask-Me-Anythings, from June 2013, from March 2016, and from December 2017.

This December 2009 Interview on SF Signal.

This October 2011 interview on Helen Lowe's website.

This September 2014 post here on A Forum of Ice and Fire.

This 2011 YouTube video on the Orbit Books channel.

This April 2014 interview with George R.R. Martin on Rolling Stone.

Adam Whitehead's History of Epic Fantasy on his blog, The Wertzone.

I sincerely hope you enjoyed. This must surely be the longest post I've made on Steemit since my initial review of the soundtrack of the first Vandal Hearts one year ago and it may well be longer even then that. As I write, this post is so long that as I type there is a delay between my fingers hitting the keyboard and the letters appearing on screen. (My average typing speed of roughly 90 words per minute likely does not help.)

I think that The Dagger and the Coin can lay better claim to being the fantasy of the decade than any other. I say this because while it plays upon many familiar fantasy tropes it also draws inspiration from the twentieth and the twentieth-century in its themes. It's a fantasy sophisticated and intelligent in its themes and willing not merely to present its ideas to you but also to think about them, to make statements about them.

It is, if nothing else, one of my favorite fantasies ever and I think it deserves a wider audience.