It’s that time again for another instalment of endangered animals, I always try to highlight animals that may not be as well known as some of the species that are frequently in the public eye.

The Okapi is definitely one of those animals, being endemic to a single region of Africa they have managed to slip under the radar of most people which is surprising considering that are one of only two species in an entire family group of animals, more surprising still is the fame of the other animal which is seen as an iconic African animal.

The plight of the Okapi is one steeped in bloodshed and political turmoil and their future existence as a species will likely be dictated by whether or not Humans can learn to coexist peacefully with the world around them.

Description

The Okapi (Okapia johnstoni) are the single extant member in the genus Okapia, and are one of only two extant species in the family Giraffidae, the other being the more commonly known Giraffe(Giraffa).

They are commonly referred to as the forest Giraffe or Zebra Giraffe, their closest living relative today is the Giraffe and they are theorised to have shared a common ancestor that lived roughly 11.5 million years ago, at a glance it is not difficult to see how they might be closely related.

Their general body shape resembles that of a Giraffe that has been squished to smaller proportions, they have the same sloping back and elongated neck, though the elongation of the neck is much less pronounced in the Okapi, despite this they have exactly the same number of cervical vertebrae as the Giraffe, at 7.

Their legs draw comparisons to that of a Zebra in that they are white with distinct black stripes on the thigh section, the lower sections of the legs is most commonly plain white with a single black/brown circlet around the ankle, the white/striped pattern ends abruptly at the rump and torso which is almost always a dark reddish-brown colour.

Whilst large sections of their body are this colour, their face, chest and throat are normally a greyish-white colour, all of these colour patterns combine to offer the Okapi fairly effective camouflage in their dense rainforest environment.

Sexual dimorphism is present in a number of factors, the most distinctive being the presence of horns (ossicones) on males, these horns are covered in fur and are short growing to only 15 centimetres in even the largest of individuals, females also possess ossicones, though they are far less pronounced and are known as “hair whorls”.

The other differing traits are based mainly on size and colour, females are usually taller than males when fully grown, though only by 5-10 centimetres at the shoulder, females are also more commonly slightly redder in appearance, in similar aged individuals the easiest method of sexing them is to simply view the genitals which are easily observable.

On average Okapi grows to a shoulder height of 1.5 metres and reach body lengths exceeding 2.3 metres, healthy individuals should weigh between 230-350 kg’s though this is variable throughout their range.

Their diet consists mainly of leaves, grasses, flowers, branches, fruits and fungi, they are obligate herbivores and are ruminants, they are predominantly browsers and they use their long (18 inches) tongue to grasp and pull at herbivorous matter, a trait that they share with their Giraffe cousins.

Another notable trait that they share with the Giraffe is their gait, unlike most other ungulates, both animals have what is known as a pacing gait, which involves both the hind and front leg on the same side of their body stepping simultaneously, this is in contrast to other ungulates such as Horses that alternate their strides.

They are diurnal animals and have well developed eyes with an increased number of rods which allows for impressive night vision, despite their vision they frequently only active during the day and may only continue to exhibit feeding behaviour for a few hours after darkness has ensued.

As even-toed Ungulates they have glands present that on their limbs that offer chemical communication, the Okapi has interdigital glands between their toes on all four of their feet, being more prominent on their fronts, these glands secrete a chemical compound that can be detected as a scent by other Okapi, the information transferred may include sex, sexual receptiveness and territorial boundary.

Habitat and Population

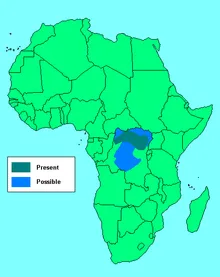

The Okapi is a species endemic to the northern rainforests of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DCR), they inhabit dense forests at altitudes of between 500 and 1500 metres above sea level, du3 to their elusive nature and common habitat they were not discovered until the 20th century.

They are very picky when it comes to finding a suitable habitat, for the Okapi it is either the dense untouched rainforest… or the dense untouched rainforest, they do not inhabit the small forests that are frequently found along rivers (gallery forests) and do not do well in the open terrain favoured by the Giraffe.

They will also not stay nearby a newly developed Human settlement or an area affected by activities such as mining or logging, they are private and elusive and require a specific ecological environment to survive, an environment that is becoming increasingly rare in the modern world.

The expanding population of the DRC which is growing at a rate of 2.6% annually has seen the Okapis range shrink dramatically over the past 25-50 years which has resulted in a sharp population decline, sustainable populations are currently known to exist in central, northern and eastern regions of the country, and it is speculated that a small population may exist south of the Congo river.

Their exact population figures are not known for reasons that will be covered later in the article though rough estimates based on limited dung surveys indicate that as many as 22,000 animals may be present in the wild, pessimistic estimates are however closer to 10,000 individuals, without surveying it’s impossible to know which figure is more accurate.

Nevertheless, their population is almost certainly on the decline, and the IUCN has noted a likely population decrease exceeding 50% in the past 25 years.

Reproduction

As with any endangered animal, the most important factor for their survival is their ability to procreate, generally it is species that have a high rate of reproduction that are more easily able to combat and adapt to threats to their existence, there’s a reason why Rodents are the dominant mammals in urbanised territory.

Okapi are generally solitary animals that exhibit territorial behaviour, their territory normally encompasses between 1 and 1.5 square kilometres, it is thought that the Okapi only come together to procreate.

As animals that inhabit a region close to the equator their environment remains stable throughout the year, as such they do not have a breeding season dictated by seasonal change and can begin exhibiting breeding behaviours at any time during the year.

Courtship and copulation is not a complex endeavour, once a female enters oestrus she will begin to emit pheromones both through spraying her urine and through her interdigital glands on her feet.

A male’s receptiveness will be dictated by the receptiveness of a female, as such males may mate several times per year with numerous females.

Once a male has detected a female in Oestrus he will proceed to find her, once found basic courtship behaviour will begin, both the male and female will circle each other whilst licking and smelling one and other, the male will then begin a display of dominance where he will throw his head rigorously and extend his neck, after the display he will proceed to mount the female and copulate with her, once complete he will return to his home territory.

Like Giraffes they have a very long gestational period which last on average between 440-450 days, after which a solitary 15-30 kg calf is born (twins are exceedingly rare), the birthing process takes between 3-4 hours on average and the female will stand throughout the event.

Like all ruminants the infant is able to stand and walk within a very short time frame after being born, normally between 20-60 minutes after birth.

The calves have adapted a very strange behavioural trait in that they do not defecate for the first 7-8 weeks of their life, it is theorised that this behaviour exists as a method of protecting the calf from predator detection, during this time the calf may double or even triple in weight making them less vulnerable to predation.

The calf is fully weaned by the age of six months and is thought to depart from its mother between 6-12 months of age, the female Okapi reaches sexual maturity at 1.5 years of age whereas the male is sexually mature at the age of 2, female Okapi are thought to become sexually receptive within several months of successfully raising a calf, infant mortality is not exceedingly high in the Okapi and they can expect to have a typical lifespan of between 20 and 30 years in the wild.

As it takes at least 15-16 months for a single calf to be born the Okapi are particularly vulnerable to rapid population declines as a potential rebound could take several years, or even decades to even marginally recover from, without effective conservation their reproductive biology is simply not suited to the current status of their environment.

Threats to the Okapi

The major threats posed to the Okapi are all entirely man-made and are unlikely to end any time soon, major threats to their existence includes illegal poaching for meat and skin, illegal logging leading to habitat destruction, and lastly death by militia groups which are frequent throughout their “protected” environments.

Like any large African Mammal, they will always be met with the threat of illegal game hunting and poaching for their body parts, this is sadly just a way of life for not just exotic species on the African continent, but animals all other the globe.

Hunting for bushmeat is not a rare occurrence in the DRC and many rural communities rely on it as a primary source of income, many species found throughout the country are illegal to hunt, though the infrastructure is not in place to fully enforce the law.

As populations of smaller, more easily hunted animals begin to decline the Okapi is becoming increasingly threatened from poachers throughout the country, in fact in some regions, such as Twabinga-Mundo the Okapi is considered to be the most prized bushmeat.

Throughout the 1990’s and 2000’s the ecosystem for the Okapis range began to change drastically, following the two civil wars, and a large in flux of migrants after the Rwandan genocide it become increasingly difficult to police protected forests.

Illegal mining and logging activities became widespread and vast swathes of rainforest are now threatened, the rate of forest depletion was 2.5% per decade between 2000-2010, though this is significantly lower than other countries on the African continent it has occurred in 33% of the Okapis habitable range.

Whilst the previous two threats are serious issues they are more of a symptom of a wider problem, and that is the inability to police conservation projects as a result of widespread militia groups.

Armed militias have been an issue in the country from at least 1997 as a result of political turmoil, this has drastically reduced the ability to carry out even the most basic tasks such as ecological surveys, with the threat of being assaulted or even murdered a distinct possibility.

These rebel groups are often linked with illegal mining and logging and have significantly more firepower than the few rangers tasked with policing the protected sites, any Okapi found in a chosen site will be killed and many have died just as a result of crossfire.

In 2012 the Okapi wildlife reserve was sieged upon by a rebel militia as a revenge attack for disrupting their illegal mining projects, seven conservation workers and all 14 of the captive-held Okapi were murdered, subsequently this led to thousands of miners entering the reserve as the infrastructure collapsed.

As rebel groups continue to inhabit the region the issue of deforestation will likely become more pronounced in the coming decades, unless a civilised method of governing the country is enacted there is little to deter illegal activities where profit margins can be gigantic.

Conservation Efforts

I always get overcome with sadness writing this section as the world is filled with so many people who genuinely care for the welfare of animals, people who devote their life’s work and meaning to protecting an animal, yet their efforts are often completely nullified by external factors of hatred and greed.

As mentioned there are laws in place, it is completely illegal to kill or actively hunt the Okapi, there is also large areas of protected rainforest that are not prohibited to be tampered with, yet due to political turmoil these laws cannot be enforced by the government, who simply have a very limited control of the country.

The two largest populations of Okapi occur in the Okapi wildlife reserve (RFO) and the Maiko national park which encompass areas of 14000 square kilometres and 10800 square kilometres respectively, protected territories are pivotal to the survival of a species, though they are only as effective as the effectiveness of their policing.

With the threat of armed rebels consistent and effective conservation projects are just not feasible throughout the range of their protected territories, whilst there are many brave individuals who take on roles as park rangers they simply do not possess the manpower to drastically reduce the threats throughout the region.

I’m 100% in support of conservation, though the protection of an animal, even an entire species cannot be considered more important that the health of the people trying to make a difference, without government, or even multi-national intervention in the mentioned areas conservation work is unlikely to yield positive results, unless protection is strengthened the long-term survival of the Okapi in the wild has a bleak outlook, or at least this appeared to be the case.

Despite the risk of death, conservation efforts continued, at the forefront of it all is the Okapi Conservation Project (OCP) who conduct the majority of their work in the RFO reserve, it was this organisation that had seven of their workers and 14 of their Okapi barbarically murdered at their headquarters in 2012.

In their mission statement they state:

OCP focuses on developing an economic and educational foundation on which the Okapi Wildlife Reserve can operate. This is achieved through programs in wildlife protection, alternative agriculture, and community assistance, and by working with the Institute in Congo for the Conservation of Nature (ICCN), a government organization responsible for the protection of the Reserve.

Their most difficult task is simply reaching a point where the reserve can operate effectively, and this rests entirely on the actions of the ICCN.

To their credit they have made substantial inroads in to regaining control and installing protection of the reserve, since 2014 the ICCN has evicted over 10,500 miners from the region and has closed 23 mines, they state that 55% of the reserve is actively protected and under the control of the ICCN and OCP, hopefully this is a positive sign for the future though there is still much to be done. Figures from 2016 annual OCP report

Much of the OCP’s funding (roughly 30-40%) is derived from Zoological organisations, in 2011 Zoological organisations from North America and Europe came together to discuss how future sustainable breeding of ex-situ animals could be conducted to benefit in-situ wild populations.

International breeding programs of the Okapi are now in place and several successful births have occurred in captivity, there are currently over 100 individuals held globally, I believe increased public exposure to the Okapis issues can only be beneficial for wild populations.

To donate to the OCP who are reliant on external funding click HERE.

Final Thoughts

I find it’s always difficult to write about any species that is distinctive and unique, not that any of the animals I’ve written about are less important, it’s just an animal such as the Okapi which is the sole surviving member of its genus, there is the added risk that their extinction signals the disappearance of a unique species not observable anywhere else.

It’s clear to me that there are many people willing to risk their lives to protect these magnificent animals and the habitat they call home, it’s hard not to feel hopeful when such determined individuals exist, and it definitely restores your faith in humanity.

We can only remain hopeful that the work of the OCP, ICCN and many other organisations continue to see positive results throughout the Okapis geographic range, their future survival is in our hands and I currently feel as though the future is bright for the Okapi, though the journey still has many twists and turns to navigate.

The Death of Sudan and a Personal Statement

Today marks a sad end to an iconic animal. Sudan, the last male Northern White Rhino has lost his battle and was kindly put to sleep by vets on the 19th March 2018 after a long battle with age-related illness.

This date should never be forgotten, this is the day as a species on this earth failed drastically, this is a date that in our lifetime saw yet ANOTHER animal grows that much closer to extinction.

The reason I write this series is to reach as many people far and wide and to teach them just how important it is to save species, to change their ways, to encourage their children to be kind to animals and to be kind to the earth, to be respectful, to recycle, and to not cause more damage to our already destroyed planet.

If IVF fails, this species is gone forever, and yet there are people out there that bash zoos, that bash conservation projects that hold animals in captivity, if you are one of those people or one of those “activists” and I use the term lightly, I ask you, what do you do to help save animals from going extinct?

Do you get up every single day and drive hundreds and thousands of miles per year to look after the animals that need us the most, to provide them with ample enrichment, training programmes, provide the world’s best veterinary care, adlib food, do you give up every Christmas, every family event because one of your animals is sick and needs you the most?

Give up any free time you may have to attend conferences, not see your friends for months on end? Do you shift 50 tons of snow, sand and bark to give your animals the best homes? Do you risk your life to stand with the world’s last remaining Northern White Rhinos knowing there are poachers out there ready to end your life for their horn?

Do you continue to turn up for work every day despite knowing that several of your colleagues were brutally murdered as was the case for the people working to protect the Okapi?

The thing is, I now fear the Northern White Rhino is gone forever once the two remaining females lose their lives we will have then lost a species forever and it simply shouldn’t be happening in the modern world.

One iconic animal dies, however there are amphibians and other species of invertebrates that are going extinct every year that don’t get as much, if any press coverage.

Every day I wake up and go and take care of the animals I work with to the best of my ability and more, I try to educate people in how to take better care of their animals and also learn how I can be better for the animals both at work and at home.

Zoos have a hugely important and often understated role in saving animals, with every birth being incredibly special and all keepers around the world supporting each other in aiding the development of those babies that will go on to eventually save their species and return to the wild.

We are not in the 1920’s anymore, Zoos are not there merely for your entertainment, they are there for the future of the silent majority of animals that without our help will likely perish, if anyone who demonises Zoos took just a minute to talk to a Zookeeper instead of berating them they'd realise this.

Content Sources

More Endangered Species

If you enjoyed this article you may find some of my previous editions interesting.