I consider myself very lucky in the fact that I’m able to observe these magnificent creatures on an almost daily basis as they are part of our zoological collection and are in fact also part of an international breeding program to save the species, a program that I can say with confidence is going moderately well.

Too really appreciate their size and power you have to see them up close, our males paws are nearly half a foot in diameter and when stood on his hinds legs he measures a little under 3 metres in height, when he communicates vocally the entire zoo can hear it, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the surrounding town can too, it’s one of the loudest sounds in the Animal Kingdom and from close range it really does go right through you.

Sadly, their populations in the wild are comparative to a roller-coaster, introduced programs have their ups and then negative factors all but undo the work that had previously been done, they are a species that have been on the edge of extinction for the past 100 years, and whilst their future can be viewed with light optimism, it is far from secured.

Description

The Amur Tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) is also commonly referred to as the Siberian Tiger, like all subspecies of Tiger it is also classified as endangered on the IUCN red list and has held this status as a minimum evaluation for the past 60 years.

Under ideal conditions they are thought to be the largest subspecies of Tiger in the world, this has been a subject of dispute since the late 1970’s as wild Amur Tigers have been decreasing in size and mass from specimens studied pre-1970, as such wild Amur Tigers are now categorically smaller than Bengal Tigers, though captive individuals can still grow to a size larger than the upper range of a Bengal Tiger.

On average, healthy Amur Tigers grow to an average body length of 2.1 and 1.75 metres from their head to the base of their tail for males and females respectively, with both sexes tails measuring between 0.9 and 1 metre when fully grown, the length of their tail is more often than not similar to their shoulder-height.

The average bodyweight of male Amur Tigers today ranges from between 180 and 310 Kg’s, females are much lighter than males and on average have a bodyweight of between 100 and 165 kg’s when fully matured, this size difference makes it rather simple to distinguish the sex of mature individuals.

The largest ever recorded wild male Amur Tiger measured 3.3 metres in total body length and weighed at least 300 kg’s, in contrast the largest captive specimen measured 3.55 metres in length and weighed 465 kg’s, this particular size can be considered an abnormality and the Tiger in question was likely obese but it remains a fact today that captive specimens are larger than their wild counterparts, this is down to a multitude of reasons, predominantly the absence of food scarcity and the use of medical care.

Aside from body mass, the second easiest way to distinguish between males and females is to observe the structure of their skull, similar to Lions males have a larger and more robust skull than females, the males skull can measure as long as 40.5 centimetres though is more often sized between 33 and 38 centimetres, in contrast the females skull has a maximum achievable length of 31 centimetres, the sagittal crest of the male often sits higher than the females as well though this is a more pronounced trait in older males.

A common misconception of the Siberian Tiger is that they are white, Tigers that you can see in Zoological collections may very well be white Amur Tigers though this is simply a genetic abnormality brought on by a recessive gene, the normal colouration of an Amur Tiger is a dusty brown / orange colour that is adorned with a unique pattern of dark black stripes and blotches, generally speaking white fur only occurs around their facial area, jowls, the backs of their legs and also their undercarriage.

As is the case with many animals, their pelage undergoes changes depending on the seasons climate, in the summer the Amur Tigers fur takes on a much brighter appearance, the colouration remains a similar shade but the fur is much shorter and is more coarse and reflective, their winter coat on the other hand is much longer (40-70mm longer in places), denser and silkier which enables them to survive in temperatures that fall regularly below -20°C, the Amur Tiger undergoes two separate moults per year one in September/October (Winter pelage) and one in March/April (Summer pelage).

They have the largest paws of any Feline species, the pads of their paws are thick and are surrounded by a dense congregation of fur that forms a protective layer over the pads during the Winter months, this allows the Amur Tiger to walk on freezing surfaces with few issues, this feature in combination with retractable claws allows the Amur Tiger to create very little sound when moving across the snow which allows them to be a highly adept ambush predator.

Habitat and Diet

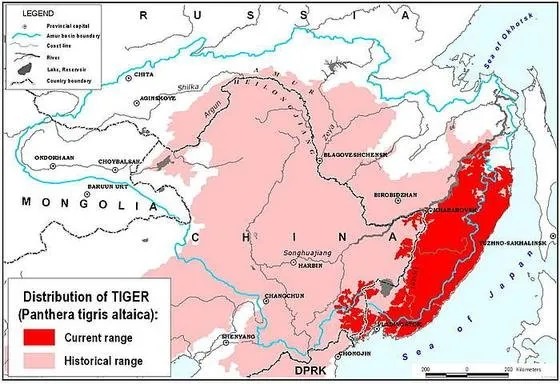

The Amur Tiger was once a commonly observed species across the Korean Peninsula, north-eastern China, Manchuria, eastern Siberia and far-east Russia, today their geographic range comprises of only the Russian far-east and north-eastern China, over 90% of wild individuals exist within the Sikhote-Alin mountain range.

Their preferred habitat is the Taiga or Boreal forest, a Taiga biome is one that comprises mainly coniferous trees such as Pines, Spruces and Larches, this biome makes up a large part of Russia’s far-east and extends throughout a large portion of China, aside from our Oceans, the Taiga is the most common Biome on the planet.

The reason that Amur Tigers favour this habitat lies mainly with their ability to hunt successfully, as large terrestrial predators they rely heavily on their ability to surprise their prey, the often-dense forest supplies the Tiger with ample cover to stalk or wait for prey and in most cases the Tiger will not attack its prey until it is within a 10-metre striking distance.

Their chosen biome also supports a wide range of Ungulate species, some of which are residential throughout the year, the bulk of their diet consists of various Deer species and wild Boar, less frequent prey includes Moose, Salmon, Hares and the occasional Ussuri Brown Bear which is thought to make up roughly 3% of their diet, Amur Tigers are apex predators within their geographic range.

The density of prey populations in far-eastern Russia are low, this leads to the Amur Tiger having a very large habitable range which they will patrol regularly, the average range for a female Tiger is 200 square kilometres and the average range for a male is 400 square kilometres, it has been estimated that an area roughly the size of Italy would be required to accommodate such large ranges if the population were to rise to the upper hundreds for mature individuals.

Amur Tigers are territorial animals and will defend their territory from other Tigers and intruders, this is true for mainly male Tigers within a small area, though can also be true for non-related females, the territory of a male in his prime may overlap the chosen territory of several females, his larger size leaves the females with very little choice but to put up with his presence, two males do not regularly exist within the same territory and may fight to the death in order to assert their dominance within the area.

Reproduction

Their reproductive habits are not too dissimilar from an animal we previously covered, The Amur Leopard, with the main similarity arising from the complete absence of the male after copulation has taken place, this is a common trait of all Feline species aside from Lions.

Amur Tigers do not have a specific breeding season and will therefore mate at any time of the year, when a female enters Oestrus she will begin to scent mark her territory with Urine and will also scratch trees to leave visual markers, the urine of the female when in heat contains a strong pheromone that attracts males to the location after it has been detected.

The Tigers sense of smell in the traditional sense is not as acute as their other senses and is not thought to be overly important for hunting, they do however have a Jacobson’s organ which is a vomeronasal organ that functions as a hybrid smell/taste function, if you’ve ever seen a Tiger pulling a strange face and bearing their teeth it’s likely because they are attempting to process their surroundings, using this organ they can detect the females pheromones from many miles away as they are carried along with the wind.

Once the male has reached the female he will stay with her for a period of up to six days, during this time the pair will be inseparable and the male will fight off any challengers, the female will only be receptive for three days and the male will mate with her repeatedly, once the female is no longer in heat the male will return to his former range, he will likely never encounter his cubs and this is true in most cases.

The female will continue her life as normal during the roughly 3-month gestation period before forming a sheltered den towards the end of the period, she will then give birth to an average litter size of two or four cubs though may give birth to as many as six cubs on rare occasions, the vast majority of litters contain an equal distribution of males/females.

During the first 8-14 days the Cubs are completely defenceless and oblivious to the world around them, their eyes are shut and their ears are closed, during this time the mother will spend nearly all of her time nursing her cubs and recovering from her birthing experience, after a couple of weeks she will need to hunt again and will leave the cubs un-attended in the den, the cubs will begin to follow her when she hunts from about two months old but they will still be reliant on her milk for another 40-50 days, despite this they will begin to eat some solid food from about two months old.

The cubs develop rapidly, and by a year-old, male cubs may be nearing the size of their mother, by 18 months old the males are ready to leave their family group and embark on their own journeys having learnt everything there is to know from their mother, at this point they will leave the territory and may travel many miles before establishing a territory of their own.

Young females on the other hand may stay with their mother for up to three years, they form a very close bond with their mother and will likely not travel far from her territory once they transition to a solitary life, as previously mentioned the territorial range of a female is on average half the size of a male, this is the reason why a solitary males territory can encompass several females, female Tigers reach sexual maturity between 3-4 years old and males often reach it at 5 years old, both sexes have an average lifespan of between 8 to 10 years in the wild, this rises to 18 years in captivity.

Threats to the Amur Tiger

In modern times the Amur Tiger is not facing the same threats that once plagued its existence, their original decline was linked largely to widespread hunting, up until 1947 it was legal to hunt the Amur Tiger and by 1922 the species had completely disappeared from a few of its former ranges, most notably the Korean Peninsula.

When the Russian government (at the time the Soviet Union) finally took notice of the severity of the issue the wild population was thought to number just 40 individuals, this number increased steadily from 1947 onward until the dissolution of the Soviet Union occurred.

After the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991 the populations of wild Amur Tigers plummeted once again, previously protected areas that were kept patrolled by Soviet taskforces were now open to outside manipulation, illegal deforestation became rife and hunters now had access to previously restricted land and, most importantly, a gateway in to the Chinese black market.

The demand for Tiger body parts for use in traditional Chinese medicines ensured that the carcass of these amazing beasts was in high demand, without a governing body to police the Tigers habitat hunters took full advantage of this and once again reduced the population to just 100-200 individuals, to this day illegal poaching is still a very serious problem which is exacerbated by the large geographic range which is difficult to police effectively, it is thought that 80% of all Tiger deaths are at the hands of Humans.

Illegal deforestation also continues to pose a threat to the survival of the Amur Tiger, as previously mentioned a single animals territory can encompass 400 square kilometres, for a population to thrive we need to ensure that their habitat is preserved, once again this is fairly difficult to police, legal deforestation is also taking place at an alarming rate as the country observes an increased rate of development, this of course requires an increase in resources as well as expansion of infrastructure, as previously mentioned, a population of just 800-900 individuals may require an area the same size as Italy.

The last threat to the Amur Tiger is its poor genetic diversity, due to the struggles endured by the animal in the past genetic markers of previous bottlenecks are present in animals today, as such the effective population size (number of breeding individuals) is far lower than the actual census population size, this issue is especially profound in the north-eastern Chinese population which is estimated to consist of at most 30 animals, a 2015 study found 17 individuals across the entire range.

As over 95% of the population exists in Sikhote-Alin mountain range an isolated population such as that seen in north-eastern China is under serious threat of becoming genetically unviable, to further add to this issue the viable population within the Sikhote-Alin range is thought to only consist of roughly 30 individuals out of an estimated 470 animals, failure to establish new populations whose territory encompasses multiple ranges will likely lead to another bottleneck and subsequent decline of the overall population.

Conservation Efforts

As previously mentioned, conservation projects originally began as early as 1947 and ended up taking a huge hit in 1991, this regulation free period only lasted for one year however before the Siberian Tiger Project was founded in 1992.

This project aimed to gain a comprehensive understanding of the Tigers present across Russias far-east and initially focused on the Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Reserve which was established in 1935, the reserve is 4000 square kilometres in size and is thought to be the home of more than 30 individual Tigers.

The project is still on-going to this day and is spearheaded by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), on their website the organisation cites the projects goals as:

The goal of the Siberian Tiger Project is to collect the best possible scientific information on tiger ecology for use in conservation plans. Through radio-tracking of more than 60 tigers since 1992, WCS specialists have studied their social structure, land use patterns, food habits, reproduction, mortality, and relationship with other species, including humans.

The data gathered through these studies is paramount to how we tackle future issues threatening the Amur Tiger, the research conducted in the wild supplies zoological and conservation-based institutions with the knowledge required to effectively take care of captive specimens with the hope of one day forming new captive-bred wild populations within viable habitats.

Luckily the WCS are not alone in their endeavours, as a rarity in conservation, the government of the animal’s habitat are a strong supporter of the protection of a species, the Russian government work directly with organisations such as the WCS through projects such as inspection Tiger which focuses on safely dealing with “problem” Tigers in a non-lethal manner.

The Russian government with WCS conducted the first ever successful capture, rehabilitation and release to a new location of any Tiger subspecies in history, by dealing with problem Tigers in a non-lethal manner the Tigers populations remain stable, the risk to the general public is reduced and the genetic viability over a wider range is improved, as such the work carried out here can potentially be performed for other struggling Tiger subspecies, you can donate to the WCS Here.

In 2010 a joint initiative between Russian and China was created, this was the first cross-border conservation project of its kind for Tiger subspecies and focused on improving and monitoring transboundary areas whilst also improving education within the involved region to help local citizens gain an understanding and respect for the animals they share their land with.

In the same year the WCS initiated another project in conjunction with the Phoenix fund (Far-east Russian wildlife organisation) and ZSL (Zoological Society of London), the project focused heavily on improving the patrol and preservation of protected areas by monitoring patrol routes, supporting the patrol teams with consumables and also offering bonus incentives for patrol teams that hit targets and perform well in the field.

Aside from projects in the wild there are various projects currently focusing on the reintroduction of Amur Tigers to their previous ranges, as well as to locations identified as viable habitats, these projects will likely take many more years before they reach fruition as the introduction of an apex predator over a large range could have a devastating effect on the ecology of that environment.

Furthermore, it is estimated that some 230 individuals exist within conservation-driven Zoological organisations, I’d much prefer to have an article dedicated to this as a subject in itself as there is so much information to explain thoroughly that it would likely leave more questions than answers, plus it’ll give me an opportunity to explain why I became a Zookeeper and what I hope to achieve and be part of throughout my career!

Further charities that are heavily involved in the conservation of the Amur Tiger include the World Wildlife Fund and the Amur Leopard and Tiger Alliance (ALTA).

Final Thoughts

When you observe the data the survival of this species, whilst still not ensured is displaying encouraging signs, from a population of just 40 wild individuals just 70 years ago, to a now stable population of roughly 500-550 the turnaround is nothing short of miraculous.

With the help of the devoted charities, governments, volunteers and Zoological organisations across the globe the Amur Tiger is one of the most heavily protected endangered animals alive today, if every endangered animal received the same focus given to the Amur Tiger the outlook for many species on the brink of extinction would be far brighter.

I hope future initiatives continue to yield positive results, and the focus on preserving this incredible species remains of high importance, the Tigers I’ve grown to love within my own Zoological collection are a constant reminder to myself that the animals we share this world with are worth looking out for.

Content Sources

- Pheromones in Mammals

- Genetic Viability of Amur Tigers

- ALTA Information

- WCS Programs

- Amur Tiger Fact File

More Endangered Species

If you found this edition of Endangered Species interesting, you may be interested in my previous posts:

- The White Rumped-Vulture

- The Yangtze Finless Porpoise

- The Saiga Antelope

- The Javan Slow Loris

- The Kakapo

- The Red Panda

- The Vaquita

- The Amur Leopard

- The Northern White Rhinoceros